Matthew 25:31–45

Sheep and Goats

Unknown artist

The Seven Works of Mercy, 1380s, Fresco, The Baptistry, Parma; AGF Srl / Alamy Stock Photo

‘You Did it to Me’

Commentary by Federico Botana

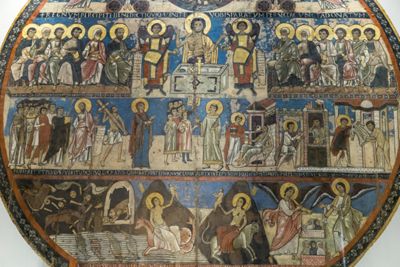

This fresco consists of individual scenes representing the works of mercy. Christ appears above each scene emerging from a cloud. He holds the Scriptures in one hand, and with the other he points down at one of the persons receiving assistance, recalling the passage in the description of the Last Judgement in which Christ exclaims: ‘as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me’ (Matthew 25:40).

This fresco is an outstanding visual testimony to the charitable practices of a late medieval confraternity, the Consortium Vivorum et Defunctorum (Consortium of the Living and the Dead), which was based in the Cathedral of Parma. In every scene, the benefactor performing the works of mercy is a bearded man with a wrinkled face dressed in a white cloak—probably the habit worn by members of the Consortium to perform good works.

The depictions of beneficiaries are also remarkable. In the scene representing the work of feeding the hungry (top register, right), we see beggars on crutches. In giving drink to the thirsty (middle register, left), one of them has lost both his hands—his stumps are dressed in bandages—and the benefactor is helping him to drink wine out of a large glass beaker. In clothing the naked (middle register, right), we see three healthy young men; the benefactor is clothing one of them with a shirt, whilst his two companions await their turn in their breeches. By contrast, the beneficiaries in lodging the stranger (top register, left) are pilgrims wearing coats and hats, one pinned with the shell of St James.

The seventh work of mercy, burying the dead (Tobit 12:12), was depicted to the right of the base of the vertical rectangle containing the six works from Matthew 25:35–36. Of this scene, only a few traces of pigment remain, but we can still see the shape of Christ's cloud and his pointing arm.

‘You did it to me’. In each pointing gesture Christ reveals his presence, incognito, in a different form. We discover just how close he may be.

Nicolaus and Johannes

Last Judgement, Second half 12th century, Tempera on wood, 288 x 243 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City; Cat. 40526, J.Enrique Molina / Alamy Stock Photo

‘The Least of These’

Commentary by Federico Botana

This monumental painted panel represents the Last Judgement and includes the first known cycle of works of mercy inspired by Matthew 25:35–36.

The cycle, consisting of three scenes, begins just to the right of the centre of the third register. In the first scene, a haloed cleric is helping a sick man to drink from a ewer. In the second, a further blessed benefactor—this one dressed like a layman in a short tunic—is comforting a prisoner. In the third scene another haloed layman is helping a naked pauper to put on a shirt. At a glance, the cycle appears to include only three of the six good deeds mentioned in the scriptural passage: visiting the sick, visiting prisoners, and clothing the naked. However, by providing water to the sick man, the cleric is also giving drink to the thirsty; moreover, he carries a basket of bread which alludes to feeding the hungry. And although the good deed of lodging the stranger may initially appear to be missing from this cycle, it was often suggested through the representation of a figure against an architectural backdrop (to suggest an indoor location before the advent of pictorial perspective). So the missing work of mercy is most likely represented here in the first and the third scenes.

This extraordinary panel was painted for San Gregorio Nazianzieno, the church of the monastery of Santa Maria in Campo Marzio in Rome, then inhabited by a community of canonesses. Together with the now very damaged frescoes of the legends of Saints Clement and Alexis in the lower church of San Clemente, it is a rare surviving example of the sophisticated visual religious culture of eleventh-century Rome.

The practitioners of the works of mercy represented here may be no more than generic portrayals of the righteous, following the late-antique convention of depicting virtues with haloes, or may represent specific saints in the Roman hagiographic tradition. For instance, they may depict the deacon Cyriacus and his companions, Largus and Smeragdus, three early Christian martyr saints who performed good deeds and were venerated by Roman female religious communities.

Unknown artist

The Allegory of Mercy, 1342–52, Fresco, Museo del Bigallo, Florence; HIP / Art Resource, NY

What You Give is What You Get

Commentary by Federico Botana

In this fresco, the seven works of mercy are depicted within eight of the eleven medallions inserted in the decorative border of the lavish liturgical cope worn by the central female figure. She is identified by an inscription on her tiara as 'MISERICORDIA DOMINI' ('Mercy of the Lord'). The first six works of mercy appear in the sequence in which they are mentioned in Matthew 25:35–36 (read left to right in descending order) and are accompanied by the corresponding scriptural passages. The seventh work, burying the dead (Tobit 12:12), is illustrated in the bottom two medallions, with a funeral procession (right) and the body of the deceased being lowered into a grave (left).

This imposing fresco was painted in the headquarters of the Compagnia di Santa Maria della Misericordia (Confraternity of Saint Mary of Mercy), today the Museo del Bigallo, Florence. The Misericordia was one of the most important confraternities in fourteenth-century Florence. The fresco illustrates, by means of a complex allegory, the role of mercy in the salvation of humankind, which is highlighted by inscriptions. For instance, to either side of the figure's head, we discover the verse in Jesus’s description of the Last Judgement inviting the merciful to take possession of the eternal kingdom (Matthew 25:34), and on the crown of her tiara a prominent Greek letter 'Tau'—in Ezekiel 9:3–9, those who were chosen to survive the destruction of Jerusalem were marked on their foreheads with the letter.

To either side of the central figure, we see groups of devotees: men to her right and women to her left. These are remarkable as characterizations of different ages and situations in life—the women in the front row are notable for their opulent costumes. Whether they represent members of the Misericordia or are just generic portrayals of Florentine citizens remains open to interpretation. Protected beneath the hem of Mercy’s robe, we discover the earliest known ‘portrait’ of the city of Florence. Indeed, by performing the works of mercy, the Misericordia was working towards the salvation of the entire citizenry.

Unknown artist :

The Seven Works of Mercy, 1380s , Fresco

Nicolaus and Johannes :

Last Judgement, Second half 12th century , Tempera on wood

Unknown artist :

The Allegory of Mercy, 1342–52 , Fresco

Works of Mercy

Comparative commentary by Federico Botana

In his description of the Last Judgement, Christ does not mince his words: those who help the needy will enjoy everlasting life, those who do not will be thrown into everlasting fire. This prophetic parable establishes a contract between Christ and humankind: he lived as a poor man and died on the cross as an act of mercy to save us; in order to attain salvation, we for our part must be imitators of him and show mercy towards those who suffer.

By the early twelfth century, theologians had transformed the six good deeds referred to in the parable (Matthew 25:35–36) into a list of deeds of alms, the corporal works of mercy: feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, lodging the stranger, clothing the naked, visiting the sick, and visiting prisoners. A seventh work, burying the dead, inspired by the deuterocanonical book of Tobit (12:12), was soon added to complete a septenary.

In the thirteenth century, theologians codified the performance of mercy to the smallest details—including questions such as to whom, by whom, how, and when alms should be given. This happened in parallel with growing numbers of laypeople flocking into confraternities and hospitals to help the poor and the sick, and an increasingly flourishing imagery of mercy. The works in this exhibition attest to the burgeoning of this attention to mercy in the Middle Ages—in theory, praxis, and art.

The cycle in the painted Last Judgement panel in the Pinacoteca Vaticana predates by several decades the canonical adoption of the sexenary in Matthew 25:35–36. We may thus gather that the aristocratic canonesses of Santa Maria in Campo Marzio were especially devoted to the care of the poor. But we must also consider the political context of the time, which saw the beginnings of the Gregorian Reform. The cycle evokes the Church of the early Christians, a society of mutual help in which all property was held in common (Acts 4:32–35). The appropriation of ecclesiastical property by nobles was one of the main concerns of the reformers; and one of the arguments they invoked to oppose the squandering of ecclesiastical benefices was that the patrimony of the Church was the patrimony of the poor. This context of reform can be credited with both the emergence of cycles of works of mercy in art and the creation of a canonical list of deeds of alms by theologians.

The other two examples illustrate the praxis of the works of mercy by laypeople in the later Middle Ages. The activities of the Consortium of the Living and the Dead, represented in the fresco cycle at Parma, are largely documented. Like most medieval confraternities, its principal activity was to conduct funerals and commemorative masses for dead members. Accordingly, burying the dead took a larger wall space than the other works of mercy—it was probably illustrated with two scenes, as we see in the Allegory of Divine Mercy in Florence. On the occasion of commemorative masses, the Consortium gave bread and wine to beggars, like those represented in the fresco. Benefactors left bequests to the Consortium to dress three paupers every year, as we also see in the fresco. And the Consortium contributed financially to the release of prisoners (the Parma scene shows not just a visit to but a discharge from prison).

In the medallions in the Allegory of Mercy, the works are not represented in such vivid detail, even though the confraternity of the Misericordia performed all the deeds represented here. Instead, the emphasis is on the salvific power of mercy. The central figure, an allegorical representation of mercy, can also be identified as the Virgin of Mercy, to whom the confraternity was dedicated—depictions of the Virgin of Mercy usually include groups of devotees to either side of the figure of Mary, whom she protects under her mantle. The central figure is, furthermore, a representation of the Church—she wears a papal tiara and a liturgical cope. More importantly, she can be considered a representation of the corpus ecclesiae mysticum, namely the Church as the mystic union of all Christians in the Eucharistic sacrifice. In the writings of medieval theologians, we discover a direct relationship between the corpus mysticum and the works of mercy—some even stress that the members of the corpus interact with each other by performing the works.

The Allegory of Mercy bring us back to the contract established in Christ’s teaching about the Last Judgement: to fully benefit from the redeeming power of Christ's sacrifice, Christians must help each other.

References

Andaloro, Marina and Serena Romano. 2006. Riforma e tradizione: 1050–1198 (La pittura medievale a Roma, 312–1431, vol. 4 (Milan: Jaca Book)

Botana, Federico. 2012. The Works of Mercy in Italian Medieval Art (c.1050–c.1400) (Turnhout: Brepols)

Le Goff, Jacques, et al. 1993. Battistero di Parma: La decorazione pittorica (Milan: Franco Maria Ricci)

Levin, William. 2004. The ‘Allegory of Mercy’ at the Misericordia in Florence (Dallas: University Press of America)

Suckale, Robert. 2002. ‘Die Weltgerichtstafel aus dem römischen Frauenconvent S. Maria in campo Marzio als programmatisches Bild der einsetzenden Gregorianischen Kirkreform’, in Das mittelalterliche Bild als Zeitzeuge: sechs Studien (Berlin: Lukas), pp. 12–123

Commentaries by Federico Botana