Revelation 12:7–12

War in Heaven

John Thornton

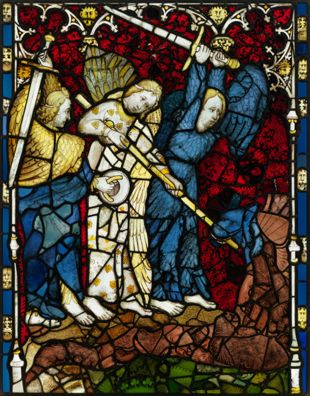

The War in Heaven (pane 7g) part of The Great East Window of York Minster, 1405–08, Stained glass, The Great East Window of York Minster; © Chapter of York: Reproduced by kind permission

Something Bigger, Stranger

Commentary by Michelle Fletcher

This is pane 7g of York Minster’s East Window, the largest expanse of Gothic stained glass in the United Kingdom. Designed by John Thornton of Coventry between 1405–08, the window consists of 311 panes, depicting (from top to bottom) God the Father and the heavenly company, followed by scenes from Genesis, and then 81 panes dedicated to Revelation. Surrounded by this superabundance of beginning and end-time imagery, pane 7g represents Revelation 12’s fight between the dragon and the heavenly angels.

Thornton’s three-on-one depiction shares many similarities with images from illuminated Apocalypse cycles (e.g. the Douce c.1260–65; Getty c.1255–60; and Queen Mary c.1400–25). Yet this portrayal is distinct. Unlike these earlier manuscripts, which represent the pierced dragon and the deadly precision of angelic lance work, Thornton represents a different moment: one where the figures are still mid-battle. The finely painted expressions on the angels’ faces show their tumultuous task and reveal that for them the outcome is still unknown. The dragon is below, his blue head biting at the lance extended towards him, while his brown body shows no wounds to indicate that his defeat is near. In this composition, the tense and ongoing battle has no clear outcome.

However, it is only one part of a vast celestialscape that illuminates York Minster’s worship space. Embedded in this sea of decorated glass, this one fight is caught up in a fusion of eternal narratives, and Revelation 12’s war scene is contextualized amongst other heavenly scenes.

As this scene soars above, light streaming through, the ways of the divine realm seem out of our grasp, and the ultimate outcome may not be clear when we only glimpse one small span. This pane holds us in the grip of turmoil—but other events swirl around it, setting such struggles amongst something bigger, something stranger: the heavenly realm breaking out into the earthly.

References

Brown, Sarah. 2014. Apocalypse: The Great East Window of York Minster (London: Third Millennium)

De Winter, Patrick M. 1983. ‘Visions of the Apocalypse in Medieval England and France’, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 70.10: 396–417

Unknown Spanish artist

Saint Michael and the Devil, c.1475–1500, Poplar, formerly polychromed and gilded, 52.4 x 22.9 x 21.3 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago; Chester D. Tripp Endowment, 2004.721, The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Stripping Down

Commentary by Michelle Fletcher

The chaos of war is transformed into quiet contemplation in this carving of Michael locked in one-to-one combat with Satan. This paradigmatic encounter is often referred to as ‘The Vanquishing of Satan’. It appears in a myriad of forms in the history of art, with Michael’s enemy being represented as a dragon, demon, and man, as the theology surrounding Satan morphs.

This intricate fifteenth-century poplar carving combines Hispanic and Flemish artistic styles to create a multifaceted sculpture, and although its origin and purpose are unknown, its ‘intimate scale’ (just over half a metre high) suggests devotional purposes, perhaps in a private chapel (Boucher 2006: 27). What we do know is that it would have originally bedazzled: polychromed and bejewelled, making radiant the leader of the heavenly army. This adorning, combined with the minute carved detail of the figure, such as the fine execution of the chain mail and the lion-faced shield, would have likely enticed the devotee into further contemplation of this highly individualized battle.

Seeing it today, stripped of the original celestial splendour and embodying post-Reformation sensibilities, we can only imagine what it would have been like to gaze on the resplendent original. Yet, this unadorned version invites us to realize that the carving itself is a ‘stripped down’ version of the battle recounted in Revelation 12: gone are the heavenly setting, the outbreak of war, and the accompanying armies. Instead, we are witness to an eerily serene combat of opponents locked in one-to-one battle.

Therefore, while the fullness of this sculpture’s original splendour might seem far away, its stripped-down form can still draw us into contemplation. Indeed, in its twenty-first-century guise it can become an encounter with a less ‘angelic’ and more manifestly ‘human’ Michael; a figure stripped of his heavenly vanguard and bedazzling radiance, and subject to the ravages of time. Yet, in spite of this, five-hundred years after its creation, they are still locked in combat. And he still fights on.

References

Boucher, Bruce. 2006. ‘“War in Heaven”: Saint Michael and the Devil’, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 32.2: 24–31, 90–91

Pieter Bruegel I

The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562, Oil on wood, 117 x 162 cm, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels; Inv. 584, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Bestial Ba/ulking

Commentary by Michelle Fletcher

Viewer, beware! War in heaven, Michael’s leading role, the dragon’s counteroffensive and subsequent defeat, and his army’s casting out and down are all packed into Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562). And this is not all. As well as the narrative swelling, the panel heaves with a vast angelic and demonic horde. In this arresting portrayal, the rebel angels descend from heaven (indicated by the circular empyrean at the top), transforming into an array of hybrid creatures and converging into a vast writhing bulk in the lower section of the painting. It is a dizzying viewing experience.

Yet a closer examination of this seething mass reveals the body of the dragon traversing the fray. Belly up, his tail runs from the empyrean down to his seven horned and crowned heads which can be seen staring into the abyss in the bottom right. The dragon’s body allows us to trace the path of his descent, and his colossal cohort swarms around his centralized form. Michael is also centred, represented as a slender figure clad in gold armour and trampling over this heaving bestial bulk. His angelic cohort populates the top register of the painting, driving down this flesh-fin-feather frenzy.

The effect is clear: as angels slash at lurid demons who gnaw on themselves and others (middle right, bottom left) and an egg-ridden bird-fish bursts open (bottom right), this bestial bulk elicits a sense of disgust. Yet, while we may baulk at these sights, the bizarre forms of the fallen angels are still undeniably beguiling when rendered in such detail and diversity.

Therefore, viewer, beware! This heady heap of hybridity provokes both disgust and desire, doing exactly what such a highly affective spectacle should: it entices us to stare a little more closely, for a little longer; to revel in revulsion.

John Thornton :

The War in Heaven (pane 7g) part of The Great East Window of York Minster, 1405–08 , Stained glass

Unknown Spanish artist :

Saint Michael and the Devil, c.1475–1500 , Poplar, formerly polychromed and gilded

Pieter Bruegel I :

The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562 , Oil on wood

Hold the Line

Comparative commentary by Michelle Fletcher

Revelation presents the line separating good from evil as very thin. (Boxall 2006: 179)

The stained-glass panel vividly conveys the push-and-pull of Revelation 12’s combat narrative: ‘Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon; and the dragon and his angels fought [back]’ (v.7).

In battle, seeking higher ground is a key tactical move, and these armed angels have done just that. However, this angelic trio are not standing high on the edge of heaven, but are balanced on a brown, earthbound ledge. Michael is at the centre—clad in white and holding his identifying lance—flanked by two others (most likely Raphael and Gabriel). Beneath, their dragonly foe’s mouth has grabbed Michael’s lance, and the leader of the heavenly armies seems locked in combat for his own weapon. The dragon is fighting back, and physical danger threatens.

Another more potent threat may also be detectable. Contamination. The feet of the angels do not trample on the dragon, but instead are separated from him. Standing on their meagre vantage point, their bodies arch away from the enemy—perhaps suggesting that the slightest contact would be deadly. This is particularly evident in the blue-robed right-hand figure. This angel’s entire body curls away from the dragon’s blue head, making the lines of separation between angel and dragon seem perilously close, both in colour and proximity.

This need to maintain lines of separation echoes the theme of purity that pervades Revelation. It continually calls its audience to avoid all manners of defilement—even to death—in order to be granted entry into the spotless New Jerusalem (21:27). Thornton’s heavenly host seem to be holding this purity line, avoiding contamination even in the closest mortal combat.

The physical lines of separation are more blurred in the poplar carving, as Satan wraps around Michael’s legs. Satan is portrayed as the dragon/demon and the artist has rendered him as a slippery character. He has many heads and various faces, so as the viewer moves around the object, the figure alters with each new angle. From one angle, Satan appears to claw at Michael in what could be one final subversive attempt, or maybe he paws at him, as an animal pleading to be caressed, or even saved. From another angle, the demon’s face appears defeated, with a leg raised in an almost surrendering stance. Yet, move a little more and an impish grin meets you from the top of the skull.

Such a multifaceted rendering reflects Revelation 12:9 where Michael’s opponent is ascribed many names. First, he is ‘the great dragon’, then also ‘the ancient serpent’, then ‘the one called the devil’, then ‘the one called Satan’, and finally, ‘the deceiver of the whole world’. Therefore, as the viewer moves around and sees the changes each new perspective brings, they can palpably perceive the slippery nature of Michael’s multiplicious foe. By rendering Satan as no one creature, but as many morphing ones, this carving facilitates an encounter with Revelation 12 which visualizes a threat hard to pin down: the plasticity of evil.

In Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Fall of the Rebel Angels we also find multiplicitous foes, but a different purpose is served by the shifting of shape. Here, the morphing of form demarcates separation between the heavenly and those that have lost their heavenly place. The angelic horde is rendered in human form (albeit winged) with the armour-clad Michael centred, trampling on and over the various forms of the vanquished. These vanquished opponents are rendered as hybrid beasts (many probably inspired by objects in contemporary cabinets of curiosities; Meganck 2015: 23–25). Altered in different ways during their casting from heaven, the bestial mass is being sucked into the abyss, with the great dragon acting as an axis for the whole hybrid host. But for all their various forms, they are united in trajectory. Unlike the hovering humanoid angels, the morphing mass is only going one way: down and away from the light. This vividly highlights the thrusting directional element of Revelation: ‘he [the dragon] was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him’ (v.9).

In Revelation 12, the war in heaven is over in just a few verses and the drama of the brief account can easily be missed. Visual renderings of this warfare allow viewers to take a ringside seat and spend time considering the tussle: the separation of sides, the dangers that prowl, and the lines that are to be held, whatever the cost.

References

Meganck, Tine L. 2015. Pieter Bruegel the Elder's Fall of the Rebel Angels: Art, Knowledge and Politics on the Eve of the Dutch Revolt (Milan: Silvana Editoriale)

Commentaries by Michelle Fletcher