Judges 4

Jael and Sisera

Marcelle Hanselaar

Jael and Sisera 2, 2007, Etching, edition 30, 212 x 281 mm, Collection of the artist; © Marcelle Hanselaar

Hospitality in Reverse

Commentary by Sam Wells

Jael and Sisera have both been criticized for breaking customs of hospitality (Conway 2016: 26).

Jael invites Sisera into her tent and then kills him (Judges 4:11 suggests her husband Heber may even have been Sisera’s ally). But is Sisera the greater transgressor by entering Jael’s tent, rather than her husband’s? His actions insult both Jael and Heber. Sisera should not have allowed himself to be persuaded by Jael; and it was not customary for guests to make requests, as he does in asking for a drink (4:19), telling Jael to stand at the entrance, and requiring her to lie by denying there was a man inside (4:20).

Dutch artist Marcelle Hanselaar sets the tale in a contemporary context. The sparse bedroom, with its compact dressing table and quizzically observant cat, suggest that Jael is an ordinary woman, in her own private space. Yet, the dressing table seems to have a second peg on it, alongside its hairbrush, comb, and cosmetics. It hints that a woman with a once conventional life has finally broken under relentless oppression, if not by Sisera, perhaps by others. Or perhaps Jael is acting on behalf of other women who have known worse than herself.

This man is truly caught with his trousers down. The portrayal is of the moment just before Sisera’s head is pierced (4:21).

Just off-centre in the picture (perhaps to suggest something out of kilter) is Jael’s face with its furrowed brows conveying concentrated energy—a picture of premeditated violence. Meanwhile the tilted mirror on the angled dressing table suggests everyday reality being thrown into reverse.

By contrast with Jael’s face, Sisera’s is almost obscured by his flailing hand. Not just he, but perhaps his whole sex, is getting its comeuppance. Men are not the centre of the story; they are about to be obscured almost altogether. In the image, Jael’s knee pins Sisera to the bed, but in a second, it will be a tent peg that does the pinning, rendering him as immobile as the tent in which he lies.

References

Conway, Colleen M. 2016. Sex and Slaughter in the Tent of Jael: A Cultural History of a Biblical Story (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

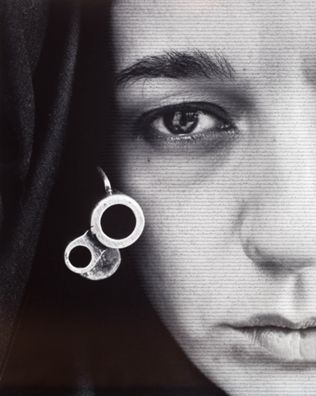

Shirin Neshat

Speechless, 1996, Gelatin silver print and ink, 167.64 x 133.35 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Purchased with funds provided by Jamie McCourt through the 2012 Collectors Committee, M.2012.60, © Shirin Neshat, courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Louder than Words

Commentary by Sam Wells

There is lively public discourse in the West about the rights or appropriateness of Muslim women wearing veils, including the hijab, chador, niqab, and burka. The pretext of this debate is sometimes the liberation of women (though some Muslim women argue veils are liberating), or the fear of something hidden underneath; in reality, the reasons are harder to pin down, and may include the feeling that one’s own values or culture are under threat or attack.

This photograph by Iranian artist Shirin Neshat is part of a series of black-and-white images of chador-clad women (full body cloak revealing eyes or face) called ‘Women of Allah’ (1993–97). In many either a model or the artist herself poses with a gun. Each photograph is covered with handwritten text, here the words of Iranian poet Tahereh Saffarzadeh in which she addresses her brothers in the Revolution, asking if she can participate:

O, you martyr

hold my hands …

I am your poet …

I have come to be with you

and on the promised day

we shall rise again.

The woman portrayed here, though serious, perhaps melancholic, appears in no way disempowered. Where we expect an earring, we see a weapon, toying with the relationship between beauty and power. Meanwhile she is not preparing for martyrdom—not readying herself to die. She is ready to kill, or at least to protect herself.

Might we imagine this woman as a kind of modern-day Deborah? Readings of Judges 4–5 often downplay Deborah’s military role and assign it to Barak (even though he refuses to go alone, and she explicitly agrees to accompany him; 4:8–9).

Likewise, Jael is cast as a wily seductress or a plucky underdog. Interpreters can struggle to see Jael as a protagonist, who in her own way, (with parallels to Ehud as assassin in Judges 3 and Deborah as judge in Judges 4–5), is advancing righteousness and justice.

This photograph encourages us to ask, why is this woman’s potential violence more troubling than Jabin oppressing Israel for twenty years and victorious soldiers exploiting women from time immemorial? If we see sadness in her face, perhaps it reflects her conclusion that there will never be a satisfactory answer.

References

Komaroff, Linda. 2015. ‘Intentionality and Interpretations: Shirin Neshat’s Speechless, 2 November 2015’, www.unframed.lacma.org, available at https://unframed.lacma.org/2015/11/02/intentionality-and-interpretations-shirin-neshat%E2%80%99s-speechless [accessed 29 January 2019]

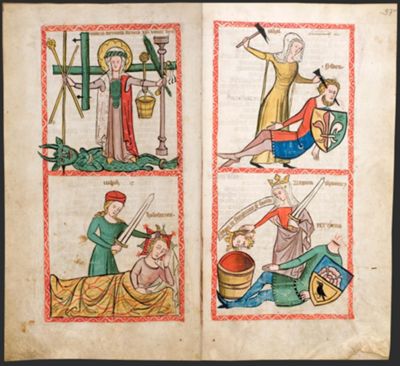

Unknown, Northwestern Germany

Jael, from Speculum humanae salvationis, c.1360, Illuminated manuscript, 350 x 200 mm, Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, Germany; Hs 2505, fol. 56v and 57r, www.tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2505 and www.tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2505/0112

A Temple Destroyed

Commentary by Sam Wells

Speculum humanae salvationis is an anonymous typological work that was popular from the fourteenth century. A figure from the New Testament is compared with three figures from the Old Testament or apocryphal literature.

In this illumination, Mary’s conquest of Satan (top left) is accompanied by depictions of Jael (top right), Judith (lower left), and Tomyris (lower right).

In the eponymous book in the Apocrypha, Judith is a beautiful widow who makes herself subject to the advances of the Assyrian general Holofernes, who is about to destroy Bethulia, where Judith lives (Judith 7). Judith then enters the tent of the drunken Holofernes and cuts off his head (Judith 13).

Meanwhile Queen Tomyris is a non-biblical figure from east of the Caspian Sea who, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, defeated Cyrus the Great of Persia and his army in 530 BCE; she found Cyrus’s body, decapitated him, and dropped his head into a wineskin filled with human blood, saying ‘I warned you that I would quench your thirst for blood, and so I shall’ (Histories 1: 214).

Mary is depicted piercing the head of Satan, while bearing a cross on her shoulders whose nails resemble Jael’s tent peg. Revelation 13:1–3 announces that the beast from the sea (later interpreted as the antichrist) also receives a mortal head wound. Meanwhile in Genesis 3:15, the serpent is told, ‘I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel’ (NRSV).

Thus Satan appears snake-like at the feet of Mary, and the particular adversary of each of the other three female protagonists is shown in similar posture: at her heel. Each of them is reversing the sin of Eve and contributing to Mary’s conquest of evil.

Interesting by her absence from this sequence is Esther. Combatting Haman—a worthy companion to Holofernes and Sisera—Esther achieves her goals not via head-wounds but through wile, political nous, and physical beauty. She appears in the Speculum praying to King Ahasuerus for her people, alongside Mary who is petitioning Christ for humankind. Petitionary prayer is depicted alongside purgative violence as a way to share in the work of Mary.

Marcelle Hanselaar :

Jael and Sisera 2, 2007 , Etching, edition 30

Shirin Neshat :

Speechless, 1996 , Gelatin silver print and ink

Unknown, Northwestern Germany :

Jael, from Speculum humanae salvationis, c.1360 , Illuminated manuscript

‘Most Blessed of Women’

Comparative commentary by Sam Wells

The victory of Deborah and Barak over King Jabin of Canaan and his commander Sisera of Harosheth-ha-goiim is told in prose in Judges 4 and poetry in Judges 5. This momentous event brings to an end twenty years of oppression of the Israelites. God is the principal agent in the story, who acts not simply to uphold Israel but to defend righteousness and justice. Thereafter peace reigns in Israel for 40 years.

God acts through three people. First Deborah, who ‘at that time … was judging Israel’ (4:4). She devises the plan by which Sisera and his army are to be defeated. Second, Barak son of Abinoam from Kedesh in Naphtali plays a complementary role alongside Deborah in winning the day, with their 10,000 warriors defeating Sisera and his 900 chariots of iron. Intriguingly Deborah remarks to Barak that the glory of the victory will go to a woman. We assume this woman must be Deborah until, third, Jael, wife of Heber the Kenite, emerges to take the decisive role. Jael invites the fleeing Sisera into her tent, offers him hospitality, and then, when he is sleeping, drives a tent peg through his temple so hard that it pins his head to the ground.

As a Kenite, Jael is not an Israelite. But God chooses her nonetheless. Her own motives are not related—creating much room for artistic speculation. The story comes hot on the heels of the tale of Ehud (Judges 3:12–30). Ehud, ‘a left-handed man’ (v.15), brings tribute to the oppressor King Eglon of Moab. Promising Eglon a secret message, Ehud draws out a half-metre sword that he has hidden on his right thigh and thrusts the sword deep into Eglon's belly, so far that the skin closes over the hilt. Ehud escapes to safety by locking the door behind him, so the slaves think the king must be ‘relieving himself’ and don’t go in (v.24).

Ehud’s and Jael’s stories each rejoice in code-transgression, humour, earthy detail, and sexual innuendo. But Jael has been particularly controversial.

The controversy is brought out in Marcelle Hanselaar’s 2007 print. Here the sexual dimension is brought out in full measure, perhaps following the briefer poetic Judges 5 version more than the Judges 4 prose account (Fewell and Gunn 1990). The key verse is 5:27: ‘He sank, he fell, he lay still at her feet [or, ‘between her legs’]; at her feet [between her legs] he sank, he fell; where he sank, there he fell dead’. In Hanselaar’s portrayal a half-naked Jael bestraddles an apparently fully naked Sisera on a bed whose sheets are tousled. It looks like they have just had sex together, and the words ‘sank … fell … sank … fell … sank … fell’ suggest a double entendre in which his energies become limp before he sleeps and then finds not just his strength but his life itself is taken from him. The tables have been turned: the potential rapist has been seduced and murdered. It is exactly the opposite of what is typical of the spoils of war.

By contrast Shirin Neshat’s 1996 photograph Speechless depicts a woman whose accessories make clear she has no need to be judged by the standards of customary hospitality. The culture of Iran post-1979 creates an expectation that a woman will be a mother, a believer, a source of perhaps ‘forbidden allure’; but here she is a person capable of violence, of killing.

In the illuminations of the Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation), we see a typological reading of the story, as is typical of a speculum. Taking the lead from Judges 5:24, ‘most blessed of women be Jael,’ the scene is taken to prefigure the defeat of Satan through the nails of Christ’s cross. Though on a literal reading it is Christ’s body that receives these nails, what is destroyed as they are driven home is the power of sin. And this is an event that takes place, notably, at the Place of the Skull (Golgotha), so again our attention is directed to Sisera’s temples.

In this light the violence of the noble Jael is no problem. Jael takes her place alongside the other warrior women depicted with her in this manuscript, Judith and Tomyris, as together they anticipate the glorious triumph of Mary. And the blood she spills proclaims that redemptive blood which will issue from Christ’s dying body on the cross.

References

Fewell, Danna Nolan and David M. Gunn. 1990. ‘Controlling Perspectives: Women, Men, and the Authority of Violence in Judges 4 & 5’, Journal of the American Academy of Religion 58(3): 389–411

To look at and compare further images from the Speculum Humanae Salvationis: http://tudigit.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/show/Hs-2505

Commentaries by Sam Wells