Judges 5

The Song of Deborah

Works of art by Jacopo Amigoni, Lee Oskar Lawrie and Unknown artist, after Saint Hildegard

Lee Oskar Lawrie

Deborah Judging Israel, 1932, Concrete, Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska; Ammodramus / Wikipedia CC0 1.0

The Just Commander

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

The first stanza of the Song of Deborah sets the stage for the ode, praising the Lord for the command of Israel’s leaders and for the voluntary commitment of the people in the uprising against their Canaanite oppressors:

That the leaders took the lead in Israel,

that the people offered themselves willingly,

bless the Lord! (Judges 5:2)

Such conditions for prosperous governance often failed to materialize in the period of Israel’s history described in Judges. But when Deborah was a judge and prophet of Israel, she took upon herself the role of military leader. By organizing and commanding the Israelites, she led Israel to victory over tyranny, and—incidentally—anarchy. Having reinstituted leadership and law and order, she was able to achieve justice for the oppressed, and a forty-year peace in the land (Judges 5:31).

The twentieth-century architects and sculptors of the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln wanted to design a building which would embody the law and tell the grand history of its development, beginning with Moses and the tablets, and culminating in the establishment of Nebraska statehood. One of the three Old Testament panels shows Deborah Judging Israel.

Deborah is enthroned on a judgment seat under her palm tree (Judges 4:5), while procuring justice for a naked woman kneeling in supplication at her feet. With her left hand outstretched she condemns a soldier who holds the woman by the hair. The representation is more allegorical than literal, with the kneeling woman apparently signifying those who throughout the book of Judges are victims of anarchy—frequently women who have been raped and/or killed by men (Haller 1993: 17).

Behind Deborah, an enslaved woman holding a fan reaches out to touch Deborah’s chair, as if she, too, is seeking release from bondage.

In contrast to the armour-clad men who clutch their spears and slaves to exhibit their physical dominance, the three bare-breasted women—one before the throne, one behind it, and one on it—extend their arms open-handed—in prayer, yearning, and the pursuit of righteousness, and so establish their even greater power.

And, as female, Deborah is fiercer in recognizing and righting the oppression and suffering of the defenceless.

Evoking the context of the wider narrative of Judges 4 and 5, where the weak retaliate against the strong and the female against the male, the relief on Lincoln’s capitol building offers a profound expression of the establishment of justice.

References

Haller, Robert. 1993. ‘The Drama of Law in the Nebraska State Capitol: Sculpture and Inscriptions’, Great Plains Quarterly, 13.1: 3–20

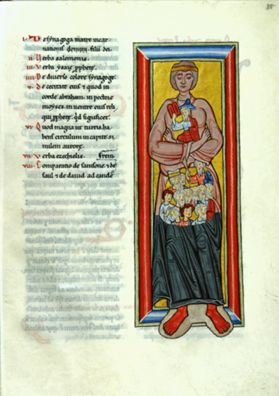

Unknown artist, after Saint Hildegard

Miniature of Synagogue, from the Scivias Codex of St Hildegard of Bingen, c.1930 after the lost original of c.1175, Hand copy on parchment, St Hildegard Abbey, Rüdesheim-Eibingen; fol. 035, Photo: St Hildegard Abbey, Rüdesheim-Eibingen

‘A Mother in Israel’

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

Thirty-five illuminations accompany Saint Hildegard’s twelfth-century masterpiece, Scivias, or ‘Know the Ways [of the Lord]’. These were painted at Hildegard’s monastery around the time of her death, and are available to us in a handmade facsimile which was faithfully copied circa 1930 (the original manuscript was lost during the Second World War).

The brilliant and distinctive illuminations of Scivias illustrate Hildegard’s mystical visions, and creatively render their extraordinary nature. Hildegard’s ‘secondary world’—that of her visions—contains great feats of architecture, unified by a principle of creation which has at its core the Incarnation.

In the fifth vision of Book 1, Hildegard describes her vision of the personified figure of Synagogue:

Therefore you see the image of a woman, pale from her head to her navel; she is the Synagogue, which is the mother of the Incarnation of the Son of God. From the time her children began to be born until their full strength she foresaw in the shadows the secrets of God, but did not fully reveal them. (Sciv. 1.5:133)

Synagogue is here represented as a mother to Israel, and ultimately, the mother of the Incarnation of the Son of God. In the illumination she stands tall, her arms crossed and her eyes closed as if in contemplation or sleep, awaiting the dawn that is Christ. Moses with his tablets are held to her chest (in pectore); Abraham and the prophets are nestled in her ‘womb’ (in ventre).

Before Deborah ‘arose as a mother in Israel’, society was unable to function, and fear and chaos reigned (Judges 5:6–7). Deborah restored order and unity to the Israelites; she gathered her people together, and protected and strengthened them, that they might carry out the will of God. As a guardian of Israel’s covenant and people, Deborah is an image of the archetypal mother Synagogue, who gathers unto herself her children. She nourishes them in the faith and guides them on the path to salvation.

References

Gutjahr, OSB, Hiltrud, and Maura Zátonyi OSB. 2011. Geschaut im Lebendigen Licht—Die Miniaturen des Liber Scivias der Hildegard von Bingen, 1 (Beuron: Beuroner Kunstverlag)

Saint Hildegard (1098–1179). 1990. Scivias, trans. by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press)

Jacopo Amigoni

Jael and Sisera, c.1739, Oil on canvas, 140 x 142 cm, Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice; Cl. I n. 1259, ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Female of the Species

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

The story of Jael killing Sisera is striking in its casual brutality. In Jacopo Amigoni’s representation of this moment, the artist creates a sharp contrast between the almost graceful movement and subdued tones of the painting and its violent, gruesome subject-matter.

Jael, who is described as ‘of tent-dwelling women most blessed’, is deceivingly generous and sweet, offering refuge and milk and curds to the general Sisera until he falls asleep, at which point she abruptly hammers a tent peg into his temple (Judges 5:26).

Jael’s expression in the painting is mild, almost tender, and her bearing is matronly and soft. Yet her figure is also broad and muscular, and a certain strength underlies her gentle exterior. Confidently swinging her ‘workman’s mallet’, she looms over the heedless and prostrate Sisera, whom she nearly equals in size (Judges 5:26).

The postures of the two protagonists are both continuous and contrasting. Their shoulders together create a diagonal line from the upper left to the bottom right corner of the painting. But in contrast to Jael, Sisera faces downwards, his expression largely hidden from the viewer, and his arms are defensively arranged, as if offering a single feeble struggle before going limp. His temple already bleeding, Jael does not hesitate, but happily takes aim with her second strike.

The story of Judges 4 and 5 plays with traditional gender roles throughout, and Jael engages in a ‘masculine’ activity: pounding a hammer and nail. By driving a peg into the general Sisera’s temple, the housewife Jael dramatically reverses the usual direction of sexual violence. The inversion of rape of women by men—a penetration now from female to male, and a fatal one—achieves retribution for it, and the conquest parallels and secures Israel’s conquest over her oppressors.

Deborah had prophesied that Sisera would be defeated at the hands of a woman (Judges 4:9). Narratively, this is the perfect poetic justice for all those who find themselves relentlessly subjugated by the strongman. But the Song of Deborah is not simply a story of righteous but cornered females conquering tyrannical males. Barak, Deborah’s general, lacks both confidence and ferocity in comparison with her, as Deborah’s pitiless and vindictive words in relation to Sisera’s hopeful mother reveal (Judges 5:28–31).

The Song of Deborah—and Amigoni’s interpretation of it—both seem to agree that, in such circumstances, ‘the female of the species is more deadly than the male’ (Kipling 1911: 379–80)!

References

Kipling, Rudyard. 2001. ‘The Female of the Species (1911)’, in The Collected Poems of Rudyard Kipling (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions), pp. 379–80

Lee Oskar Lawrie :

Deborah Judging Israel, 1932 , Concrete

Unknown artist, after Saint Hildegard :

Miniature of Synagogue, from the Scivias Codex of St Hildegard of Bingen, c.1930 after the lost original of c.1175 , Hand copy on parchment

Jacopo Amigoni :

Jael and Sisera, c.1739 , Oil on canvas

The Iron Lady Wakes

Comparative commentary by Lauren Beversluis

The relief on the Capitol Building in Lincoln, Nebraska underscores Deborah’s strength and effectiveness as a leader. Her prophetic authority, firmness, and conviction in the face of oppression are all expressed by her position and posture. Like the other representatives of the Law carved on neighbouring panels, her figure is upright, stately, indomitable—she epitomizes righteousness. She is the just Judge, the advocate of the naked and desperate female Victim. In her fortitude and integrity Deborah is structural; she is the right-angled, solid and cement-brick foundation for the Law. She represents the fundamental architecture of Israel, and she is part of the edifice of the Law that was still being built in the twentieth century and beyond. The Iron Lady in Deborah refuses to compromise on what she knows is right.

The theme of the architectural virtue of woman—or perhaps, the feminine virtue of architecture—re-emerges in the illustrated visions of Saint Hildegard. A synagogue in literal terms is a building; abstractly and etymologically it is a ‘bringing-together’ (from the Greek, synagōgē). Parallel to the Christian conception of the Church, Synagogue is personified as a mother in Scivias. It is she who keeps the family of Israel together; she is its structure and its embodied unity, its patient nourishment and growth. That Moses the Lawgiver takes pride of place in her bosom is surely significant; it is Synagogue who protects and sustains the covenant of her people Israel. It is her body which keeps her family from dissolution and destruction.

In contrast to typical medieval personifications of Synagogue, which tend to be rather more pejorative, the Scivias portrait envisions her as ‘honorable and dignified’ (Gutjahr and Zátonyi 2011: 49). Hildegard writes that:

The Synagogue is of great size like the tower of a city, because she received the greatness of the divine laws and so foreshadowed the bulwarks and defences of the noble and chosen City. And she has on her head a circlet like the dawn, because she prefigured in her rising the miracle of the God’s Only-Begotten and foreshadowed the bright virtues and mysteries that followed. (Sciv. I.5:135)

For Hildegard, Synagogue can carry Moses, Abraham, and the other prophets, and for this she is to be honoured. But she cannot ultimately save them. She can only prepare them for redemption. Like Synagogue, Deborah is in Christian interpretations like Hildegard’s an image and seed—a ‘prefiguration’—of greatness, but not its fulfilment. While she successfully gathers together many, though not all, the tribes of Israel, the peace and unification she manages to achieve will last for only forty years. She is not perfect; her efforts are not her own to fulfil. In this, too, Deborah is a mother and a citadel—resilient, but impermanent.

Completing the cycle, Jacopo Amigoni’s Jael and Sisera captures the brutal and destructive side of feminine conviction. The image is gripping: with a suggestive smile, kind eyes, and a motherly figure, Jael calmly hammers a tent peg into her victim’s head. Her reasoning is ambiguous; her personal stake (no pun intended) in the assassination is not clear from the text. She is not an Israelite, and it is not explicitly stated that Sisera made any unwanted advances towards her (Judges 5:24). Nevertheless, the killing of Sisera has militaristic and sexual undertones. It is directly consequential to the war, and it symbolically inverts and revenges the rape—both real and metaphorical—experienced by victims of violence and oppression. Perhaps surprisingly, Jael’s unflinching slaughter of her enemy is highly praised in the Song of Deborah, precisely for its utter mercilessness. The praise moves from Deborah to Jael—woman to woman, vanguard to victor.

Like the figures of Deborah and Synagogue at the Capitol and in Scivias, the figure of Jael by Amigoni also evokes strength, conviction, and even maternal care in her bearing. But the former establish order, build, create, sustain; the latter makes chaos, deconstructs, destroys, abandons. Jael overturns the normal rules of hospitality; the home turns into the battlefield, the wife into the assassin, and the means of shelter into deadly weapons. Like the tent itself, Jael appears to be defenceless, vulnerable, and welcoming. But the ‘most blessed of all tent-dwelling women’ is in reality a fortress. So disguised, she defeats the general—and the man—at his own game.

The same female battle cry that rouses the virtues of courage, conviction, and righteousness can lead to acts of deception, seduction, vengeance, and brutality. Hidden in Woman is a fearsome power to achieve victory, no matter what it may take. In other words, the lady is of iron.

Awake, awake, Deb′orah!

Awake, awake, utter a song! (Judges 5:12)

References

Gutjahr, OSB, Hiltrud, and Maura Zátonyi OSB. 2011. ‘Die Synagoge’, in Geschaut im Lebendigen Licht—Die Miniaturen des Liber Scivias der Hildegard von Bingen, 1 (Beuron: Beuroner Kunstverlag)

Saint Hildegard (1098–1179). 1990. Scivias, trans. by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press)

Haller, Robert. 1993. ‘The Drama of Law in the Nebraska State Capitol: Sculpture and Inscriptions’, Great Plains Quarterly, 13.1: 3–20

Commentaries by Lauren Beversluis