Genesis 22:1–5

The Journey to Moriah

Rembrandt van Rijn

Abraham Caressing Isaac, c.1637, Etching on paper, 118 x 90 mm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; White/Boon 1969, no. 33, State i/ii, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.7238, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Isaac, whom you Love

Commentary by Ben Quash

‘After these things…’ begins the passage. But what ‘things’ are encompassed here? We do not hear about how Isaac, the ‘child of laughter’, grew up, nor how the bonds with his parents developed before they were tested in this most extreme of tests. In this etching, Rembrandt goes into this gap in the text and imagines it. The Bible’s words that Isaac was the son whom Abraham ‘loved’ are rendered vivid in the physical intimacy of the two figures. Rembrandt shows us a moment full of familial affection between father and son, with a hint of terrible foreboding. The voice from heaven (which comes ‘after these things’) has not yet called out ‘Abraham!’, so here Abraham ‘takes’ his son in his hands but without rising and heading for the land of Mori’ah. He ‘binds’ him, but in an embrace. The child laughs, looking outwards from his father (not anxiously up at him) with an easy confidence that all is well. He has the prospect of fruit to bite into. God provides.

Abraham looks at us with a hint of something more wary. God has provided for him too: the fruit of a child in his and Sarah’s old age. His embrace of Isaac is linked on a diagonal axis with Isaac’s grasp of the fruit. Dare he have the same easy confidence as Isaac? While protectively harbouring Isaac between his legs, he holds the child just a little awkwardly—round the neck—and this caress introduces a dark connotation at odds with the scene’s lightheartedness. The legs that protect will arise and lead the boy to the land of Mori′ah. The hand that caresses will soon hold the knife of sacrifice. The throat caressed will be the knife’s target.

God has provided. The fruit must still be tested.

Jan Brueghel the Elder

Wooded Landscape with Abraham and Isaac, 1599, Oil on panel, 49.5 x 64.7 cm, Kokuritsu Seiyō Bijutsukan [The National Museum of Western Art], Tokyo; P.2002-0001, © British Library / HIP / Art Resource, NY

Figures in a Landscape

Commentary by Ben Quash

Jan Brueghel the Elder, like many artists, found in the account of Abraham and Isaac’s journey to the land of Mori′ah an opportunity to make a landscape painting, while also painting a biblical story. In the spare lines of Genesis 22, in which there are very few adjectives, a great, epic space is nevertheless evoked—a sense of height and distance. The small human figures must travel for three days across country. The mountain will gradually disclose itself to them as they draw nearer. The only significant action remarked upon throughout the duration of this long first leg of the journey is Abraham’s raising of his eyes to espy it: he ‘lifted up’ his eyes (v.4), so we imagine the mountain rising above him.

In this painting, height and distance are rendered very effectively. Vast, overarching trees dwarf the characters, and a gap in the forest opens onto misty distances that successively recede—dropping from mountainous outcrops to a wide valley floor, and then to further distant mountains. There is also an unfathomable depth to the forest’s dark interior.

This affects the way we view the figures in the landscape. Their activity is concentrated in a comparatively small space, and we are briefly tempted to imagine their passing through as inconsequential. They exchange the time of day with some woodcutters. Abraham has also cut wood (v.3), and Isaac carries it; from a distance, how different are they from these ordinary workers? Yet at the same time, we know that there is nothing inconsequential about either these people or the objects they carry. There is another ‘hugeness’ to be discerned here, alongside the hugeness of the landscape: it is the hugeness of the human-divine drama (played out in the proving of Abraham’s—and God’s—faithfulness), the hugeness of a nation’s destiny. The dramatic intensity packed into the small area of the canvas occupied by the human beings is as overwhelming as the landscape and as unfathomable as the forest’s gloom.

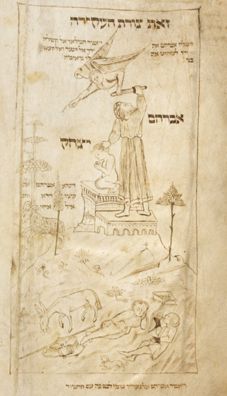

Joel ben Simeon

Sacrifice of Isaac, from Commentary on the Pentateuch, part 2, 1460s, Illumination on parchment, 240 x 170 mm, The British Library, London; MS Additional 14759, fol. 1v, www.bl.uk

‘Where I am going, you cannot come’

Commentary by Ben Quash

On this illustrated Hebrew manuscript page, we are invited to wonder what Abraham’s two attendants did while he went on alone with Isaac. The young men lie on the grass on either side of a small stream of running water. It has been a long, three-day journey and they are worn out. So—their thirst slaked—they rest, while the donkey feeds on the grassy foothills of the mountain. One of the young men has fallen asleep.

Abraham and Isaac must face the next part of their ordeal without company, and in foregrounding the two attendants like a sort of barrier, the artist awakens our sense that we, too, might be trespassers if we tried to journey onward to the mountain summit.

Abraham’s only explanation to the attendants is that he is going some way further (‘yonder’, v.5) in order to ‘worship’. Just what might this ‘worship’ be?

Whatever visual models the artist may have had in mind in decorating this page, the reclining postures of the attendants may seem to us reminiscent of figures in Christian tradition. We might see in them the prostrate forms of the sleeping disciples who could not stay awake with Jesus in his hour of agony in Gethsemane (Matthew 26:36–46; Mark 24:32–42; Luke 22:40–46). Because Peter, James, and John could not accompany Jesus in that great test, he, like Abraham, had to face his ordeal alone. Maybe Abraham’s act of ‘worship’ can be read in conjunction with Christ’s agony as an offering to God—almost too painful to bear.

Or are the attendants a little like the soldiers outside Christ’s tomb after his death and burial, traditionally shown sleeping—ignorant of the fact that what looks like a place of death is destined to unleash resurrection life? Some rabbinic commentators suggest that Isaac really did die on Mount Mori′ah, but was restored to life again. In this light, like Christ, Isaac embodies the victory of God’s promises even over death. The cost, though, is hard to reckon for those of us who look on from a necessary distance towards this ‘yonder’.

Rembrandt van Rijn :

Abraham Caressing Isaac, c.1637 , Etching on paper

Jan Brueghel the Elder :

Wooded Landscape with Abraham and Isaac, 1599 , Oil on panel

Joel ben Simeon :

Sacrifice of Isaac, from Commentary on the Pentateuch, part 2, 1460s , Illumination on parchment

‘Behold me!’

Comparative commentary by Ben Quash

In Genesis 22, Abraham both discloses himself and also seems to remain hidden. He is addressed three times in the course of the chapter—first by the voice of God, then by Isaac, and finally by an angel. His response is the same in each instance: hinneni/hinnenni, which is often translated ‘Here I am!’, but means something more like ‘Behold me!’

The exclamation is rich in meaning. It has connotations of ‘beholden-ness’: Abraham is a duty-bound man. It also contains the command ‘hold me!’: the child’s cry to be held and loved (a cry to which Abraham is preparing to close his ears in his binding of Isaac). But at a literal level, ‘Behold me!’ also simply suggests a willingness to be seen.

Artists have responded to the challenge of ‘beholding’ Abraham in this last way, and they help us to do the same. They show him. But what sort of a man do they show? As the literary theorist Erich Auerbach (1953: 9) has pointed out, in the text itself, ‘nothing is made perceptible except the words in which he answers God ... with which, to be sure, a most touching gesture expressive of obedience and readiness is suggested, but it is left to the reader to visualize it’.

In Rembrandt’s drawing, Abraham’s gaze meets ours directly, asking to be reciprocated, but by no means giving everything away. It is guarded as well as engaging. This simultaneous advance and retreat enacts, in a facial expression, the journey of Abraham and Isaac more broadly. With his ‘Behold me!’, Abraham steps forward to accept his commission, but his stepping forward is also a going away—first from Sarah, and later also from the attendants he leaves behind to enact a ritual they cannot be permitted to behold. Their sleepy demeanour in the illustrated Hebrew manuscript enhances their detachment from what is going on: theirs is a nescience as blithe as the donkey’s. And despite the best efforts of our imaginations, Abraham and Isaac seem to leave us behind too. Their thoughts and feelings are not explained to us; it is a strange and terrifying task that Abraham has undertaken to perform, and Isaac’s role in it is incomprehensible, to him, to us, and (perhaps) to Abraham himself. Again, Abraham withdraws even as he steps forward.

In another way, the fame of this story means that we are already ahead of him, awaiting his arrival. In Brueghel’s painting, we are given a perspective on this vulnerable band of people from above. It is as though we are already on the mountain, seeing them painstakingly draw nearer. However, even knowing the story, and knowing Abraham’s destination, we are unknowing of so much. We see Abraham, but we are conscious at the same time that we can see only a fraction of what there might be to see: no facial expressions; neither zeal, nor the drawn lines of sorrow, nor fear. He is under our gaze, but far from us—even further below us in Brueghel’s painting than he is above us and ‘yonder’ (v.5) in the Hebrew manuscript. Brueghel’s painting asks us to be patient, for it is not yet clear what Abraham will be shown to be when his ascent is finally accomplished.

In all three images, in different ways, Abraham is on display but opaque, known and unknowable. Perhaps this puts us in the position not only of the attendants but of Isaac, held close to Abraham’s body or walking close at his side, but in the dark about what he intends.

References

Auerbach, E. (1953). 'Odysseus’ Scar', in Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. by W. R. Trask, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Commentaries by Ben Quash