Revelation 21

The New Jerusalem and the Gates of Heaven

Works of art by K.O.S. (Kids of Survival), Mark Wallinger, Michael Takeo Magruder and Tim Rollins

Mark Wallinger

Threshold to the Kingdom, 2000, Video, projection, colour and sound (stereo), Duration: 11min, 12sec, Tate; Presented by Tate Members 2009, T12811, © Mark Wallinger, Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

A Discomfiting New Jerusalem

Commentary by Eleanor Heartney

British artist Mark Wallinger is best known for his explorations of loaded issues like class, British heritage, nationalism, and imperialism. But he has also drawn on his Church of England upbringing to create sculptures, photographs, and videos that deal with the intersections of religion and politics. In such works, quotidian settings like classrooms, underground railway stations, and airports become stand-ins for the sacred realm.

In his film Threshold to the Kingdom, Wallinger transforms the international arrivals door at London’s City Airport into an unsettling version of Judgement Day. This video was filmed surreptitiously in 1998 as travellers made their way out of the airport. They walk through the door, some slowly and apparently disconcerted, others purposeful, and yet others happily waving to waiting loved ones. As they pass a hidden camera they suddenly vanish, as if into another realm. The video is presented in extreme slow motion to the choral accompaniment of Gregorio Allegri’s sublime hymn of atonement, ‘Miserere Mei’.

Here, as the title of the work suggests, the airport serves as a metaphor for the gates of heaven. But it is an ambiguous symbol. Wallinger explains that the work was inspired by his own fear of flying and his discomfort with the heightened security measures at these places of arrival and departure. The airport, he remarks,

is where we experience the power of the state at its most overt: we are being judged, which I realized was analogous to confession and absolution in the Roman Catholic Church. (Bois et al 2008: 196)

In this work, the gauntlet that the faithful must undergo to achieve salvation is re-imagined in terms of the authoritarianism, the surveillance, and the potential humiliation and exclusion that are now part of the travel experience. As a result, Paradise, when finally achieved, begins to seem more akin to prison than to the glories of the New Jerusalem.

References

Bois, Yve-Alain, et al. 2008. ‘An Interview with Mark Wallinger’, October Magazine, 123: 185–204

Tim Rollins and K.O.S

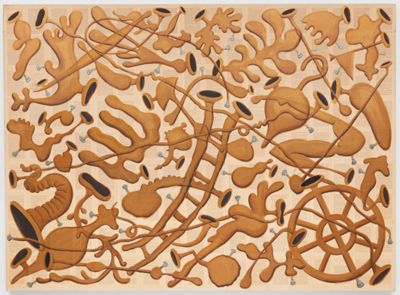

Amerika the Stoker, 1993, Acrylic on book pages on linen, 167.6 x 231.1 cm; Courtesy of Studio K.O.S., Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul; Photo: Matthew Herrmann

An American New Jerusalem

Commentary by Eleanor Heartney

In his evocation of a ‘shining city on a hill’, Puritan leader John Winthrop (1588–1649) cemented the idea of America as the earthly site of the book of Revelation’s New Jerusalem. One of the most eccentric versions of this idea appears in the final chapter of Franz Kafka’s novel Amerika (written 1911–14). In this unfinished work, Kafka envisions America, a country he never visited, as a land of lawless opportunism and arbitrary authority. His beleaguered hero Karl Rossmann arrives, after many trials and tribulations, at the gates of the Nature Theater of Oklahoma. This institution serves as a metaphor for America’s promise as the land of new beginnings. At the entrance to the Theater, Karl is greeted by a host of angels creating a fearful din as they make very disharmonious music with their golden trumpets.

This comic scene is the basis of a series of paintings produced by the Art and Knowledge Workshop of Tim Rollins and the Kids of Survival. An American artist collective, the Workshop employs works of classic literature as teaching tools for groups of at-risk urban teenagers. Under the guidance of Rollins, who is the Workshop’s founder, the Kids of Survival transformed the last scene of Kafka’s Amerika into a celebration of creative freedom.

The Amerika paintings present intricate compositions of multifarious and entwined horns whose forms are drawn from such popular and high cultural sources as the Italian Renaissance artist Paolo Uccello’s battle scenes, African masks, Santeria icons, Hollywood horror films, Louise Bourgeois sculptures, and birds in flight. Painted in gold over the spread-out pages of the book itself, they give exuberant visual form to the promise of renewal and rebirth embodied by the New Jerusalem, a home ‘for those who are written in the Lamb’s book of life’ (Revelation 21:27).

Michael Takeo Magruder

A New Jerusalem, 2014, Real-time VR installation and soundscape, Dimensions variable, [Left] Installation in 'And I Will Take You to Paradise', Art Museum KUBE, Norway ; [Right] Internal view from the Oculus Rift VR headset; Images: copyright and courtesy of the artist

A New Jerusalem for the Twenty-First Century

Commentary by Eleanor Heartney

Michael Takeo Magruder’s A New Jerusalem is an immersive installation that presents the heavenly city as a dazzling virtual reality environment that only exists in the fourth dimension. It is part of a larger exhibition titled ‘De/coding the Apocalypse’ created to bring the book of Revelation into the digital age.

Each of the five installations that comprise this exhibition is designed to bridge the gap between this ancient text and the wired world using such tools as 3D imaging, video game technology, Google search engines, and digital code. While the other installations dwell on the spectres of war, devastation, and destruction that have driven prophecies of the apocalypse from the first century CE to the present, A New Jerusalem offers a more hopeful vision. Using descriptions from the book of Revelation, Takeo offers two views of the New Jerusalem. Presented on a screen, one can view it from the outside as a golden cube with twelve gates that slowly descends from on high. Or, with the assistance of VR glasses one can virtually enter the city and become enveloped by shards of golden light.

To create the architecture of these two perspectives Takeo has combined code generated from the text of the book of Revelation with data from Google Maps of present-day Jerusalem. By this use of advanced technology, Takeo is able to suggest a doubled vision of the New Jerusalem as a place that exists simultaneously above and below, in imagination and in fact. He melds the mythical and actual Jerusalem.

Abstracted and transformed, these two codes create a structure that is at once based on a concrete reality yet unlike anything that might exist on this earth. ‘Coming down out of heaven from God, having the glory of God, its radiance like a most rare jewel’ (Revelation 21:10–11).

Mark Wallinger :

Threshold to the Kingdom, 2000 , Video, projection, colour and sound (stereo)

Tim Rollins and K.O.S :

Amerika the Stoker, 1993 , Acrylic on book pages on linen

Michael Takeo Magruder :

A New Jerusalem, 2014 , Real-time VR installation and soundscape

The New Jerusalem in a Post-Utopian World

Comparative commentary by Eleanor Heartney

The book of Revelation describes an angry God’s just punishment of sinful humanity. But however dreadful it may be, the end of history is also a beginning. Following the apocalyptic passing away of the old heaven and the old earth, John of Patmos describes his vision of the New Jerusalem as, at once, a city of gold, a verdant garden, and a place of rest for the weary and downtrodden. The arrival of the New Jerusalem heralds a new order of peace and harmony for the just and virtuous. This is an idea which has shone through the last two millennia as a beacon of hope, inspiring utopian thinkers as diverse as Thomas More, Jonathan Edwards, William Blake, H. G. Wells, and, even in a recent prose poem, punk icon Patti Smith.

However, there are ambiguities inherent in the notion of the New Jerusalem. For centuries, scholars, theologians, and believers have debated its meaning and status. Is it literal or metaphorical? Will it exist on earth or only in some dematerialized hereafter? Is the idyllic state to come something entirely new or a return to a golden age of the past? Should humans strive to perfect the world in which they live? Or should they wait out the trials and tribulations of their times in anticipation of a paradise that will arrive after the destruction of the world as we know it? Will the New Jerusalem come only after wholesale human suffering and destruction? Is the idea of Paradise and its promise of regeneration ineluctably tied to sectarianism and strife?

Such questions have also inspired numerous contemporary artists. Following the wreckage of the twentieth century’s utopian dreams, they tend to cast an equivocal eye on promises of a more perfect world. The three artists here approach the idea of the New Jerusalem from very different perspectives, but in each case, the promise of redemption and renewal is tempered by the realities of history and human nature.

Of these three artists, Michael Takeo Magruder presents the most hopeful vision. Using virtual reality, he envisions the New Jerusalem as a glittering, jewel-like fantasy. However, the larger work of which this installation is a part is haunted by the artist’s memories of his Cold War childhood. And indeed, much of the technology that he employs was developed by the military for less uplifting purposes. Thus, while the VR, digital code, and 3D imaging that he employs are the epitome of modernity, Takeo’s work forces us to question whether humanity has made progress on any other front.

Similarly, the Amerika paintings of Tim Rollins and the Kids of Survival present joyous images of creative freedom. But the source that they reference is far more ambivalent about the promises of the New Jerusalem. Kafka’s Amerika is more demonic house of mirrors than shining city on a hill. And the cacophony that envelops its gates deliberately undercuts the promises of harmony and order we normally associate with Paradise.

Mark Wallinger’s vision of the New Jerusalem is equally sceptical. By re-envisioning the gates of paradise as the airport’s arrival door, he collapses the sacred and the secular. In doing so, he suggests that the slings and arrows we suffer in the here and now will not be ameliorated in the hereafter.

The book of Revelation’s New Jerusalem presents an uplifting coda to a saga otherwise dominated by dark visions of death and destruction. Today, fears of global warming, nuclear holocaust, global famine, and worldwide pandemics render the dangers that underlie this apocalyptic narrative all too plausible. The promise of a New Jerusalem, on the other hand, is a promise of hope. But hope, these contemporary artists suggest, remains more challenging than ever to imagine.

Commentaries by Eleanor Heartney