Revelation 22

Paradise Restored

Unknown artist

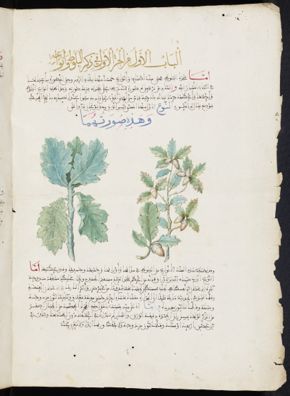

A sheet from an Arabic manuscript on botany (Kitāb al-Durar wa-al-wuqūf ʻalá al-aʻyān wa-al-ṣuwar), 16th century, Illuminated manuscript, The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; MS. Laud Or. 156, fol. 1b, ©️ Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Apocalyptic Herbalism

Commentary by Clementine Kane

...and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. (Revelation 22:2b)

Christ came as a healer, offering renewed life in abundance (John 10:10) to those who thought theirs was over. Many artists and theologians have interpreted the tree of life in Revelation 22 as an allusion to Christ on the cross, and the leaves as an extension of his healing sacrifice. While we in modern times generally think that medicine comes in pill form, most earlier cultures relied on the knowledge of how to use ‘healing leaves’ to achieve therapeutic results—in short, herbal medicine.

This page from an Arabic herbal (a book of plants and their medicinal properties) also shows a leaf for healing—an oak leaf whose purported therapeutic properties range from treating ulcerative colitis to alleviating placenta previa. Herbals such as this one, and the knowledge associated with them, were the mainstay of ancient and medieval medical knowledge. This knowledge was rooted in the theory of the four humours espoused by the ancient Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen and transmitted to Islamic culture through the writings of many philosophers and physicians, including Ibn Sīnā/Avicenna (980–1037 CE).

In the time and place of this manuscript, medicine was considered to be shared intellectual capital. Where cultural and political boundaries existed between the European and Islamic worlds, especially in the realms of religion and military activity, scientific and especially medical exchange seemed instead to connect these cultures in a common endeavour. This herbal is a rare visual manifestation of that cooperation, as it combines an Arabic text adapted from European herbals with botanical paintings based on European woodblock prints of the mid- to late-sixteenth century.

The Muslim author of this manuscript could never have dreamed that his work would be used to illuminate a biblical commentary as it is here. Nevertheless, this herbal shows that healing leaves can be a first point of connection between cultures, the first indication of the renewal that is so potently unveiled in John’s vision. Christ came as a healer, and by pursuing healing with the plants he breathed into life, his followers embody him until he himself, as the tree of life, can offer the leaves of healing that cure for an eternity.

References

Kane, Clementine. 2021. In Between Cultures: Uncovering the Book of Pearls and Knowledge of the Essences and Forms (Oxford: University of Oxford)

Matar, Nabil. 2005. ‘Arab Views of Europeans, 1578–1727: The Western Mediterranean’, in Re-orienting the Renaissance: Cultural Exchanges with the East, ed. by Gerald M. Maclean (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 126–47

Pieter de Hooch

Woman lacing her bodice beside a cradle, c.1660–63, Oil on canvas, 92 x 100 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; No. 820b, Berlin State Museums, Gemäldegalerie / Christoph Schmidt

Faithful Living

Commentary by Clementine Kane

Let the evildoer still do evil, and the filthy still be filthy, and the righteous still do right, and the holy still be holy. (Revelation 22:11)

Commenting on this initially perplexing verse, the sixth-century Greek philosopher Oecumenius reminded his readers that:

[John] is not urging or commanding anyone to do that which is wicked or to defile themselves. Rather, he is saying that the short time remaining gives humankind yet an opportunity. Therefore, let each person do that which is pleasing to them, and let them use their free will as they choose, whether for that which is evil or for that which is good. (Weinrich 2005: 399)

We humans can choose to work towards the new heaven and the new earth or we can waste this fleeting moment we call ‘life’ in greed, pride, envy, and strife. Our choice is important; as John Walvoord puts it,

There is a sense also in which present choices fix character; a time is coming when change will be impossible. Present choices will become permanent in character. (Walvoord 1966: 335)

The final verses of Revelation contain words of warning and benediction. They also contain a message which arcs back over the whole of Revelation, offering a guiding thread for its interpretation. The thread is this: Christ is coming soon—live faithfully.

Pieter de Hooch’s calm domestic scene can illuminate what it might look like to live faithfully in joyful anticipation. A woman gazes at a cradle as she laces her bodice after breastfeeding her infant, tired yet content. She is in the throes of life-making and life-giving; it is the creative, generative, nurturing work all humans are called to, whether through the bearing and raising of children or in other forms. End times or no, humans are still going to create and nurture life.

Look deeper, and this painting, in all its serenity, has another element that expresses a sense of joyful anticipation. The child in the background stands at an open doorway through which streams golden light. In the lifted heel we sense her anticipation, and the warmth of the light suggests that she can expect something good—a beloved father or a playmate. The figures in de Hooch’s intimate painting are in a reciprocal relationship with life itself, giving, receiving, and anticipating.

References

Weinrich, William C. (ed.). 2005. Revelation, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, New Testament, 12 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press)

Walvoord, John F. 1966. The Revelation of Jesus Christ (Chicago: Moody Press)

Unknown artist, Greece

Head of Aphrodite, later carved with a cross, 1st century CE, Marble, National Archaeological Museum, Athens; no. 1762, George E. Koronaios / Wikipedia / CC BY-SA 4.0

Image Bearers

Commentary by Clementine Kane

They will see His face, and His name will be on their foreheads. (Revelation 22:4)

What might the name of God inscribed on our foreheads look like? The sixth-century Iberian bishop Apringius of Beja read it as both an experience and a literal marking:

They shall rejoice in the vision of his face and in the sweetness of his presence, and they shall bear his name engraved in the sign of his cross on their foreheads. (Weinrich 2011: 60)

Since their early history, Christians have been known by the sign of the cross. It is the way that we inscribe God’s name on ourselves in this life. And wherever Christians have gone, crosses have followed, painted, drawn, or in this case carved into the forehead and chin of a statue of the ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite. The gesture of carving the cross into the goddess is paradoxically iconoclastic and sanctifying. It is an inherently violent act intended to break the power of the goddess and submit her (and everything she represents) to Christ.

Yet simultaneously, this act of desecration can connote an act of consecration because of the use of the cross. Read eschatologically, it anticipates the reach of the sanctifying power of Christ’s cross to all creation. The statue, and everything she represents, is set apart for a new God and a new purpose. She is not obliterated. And although some of Revelation’s language can indeed suggest the erasure of the entire pre-existing material world and its human culture (‘the old heaven and the old earth have passed away’; 21:1), it is transformation, not obliteration, that dominates its final vision, begun in Revelation 21 and culminating in 22:4.

How is the defacement of this statue redeemed in the apocalypse? The apocalypse is literally ‘the unveiling’, the revelation that even this goddess, this female archetype, so roughly ‘baptized’, is extended healing as much as she represents the human attributes of love, fertility, beauty, and sexuality: all entirely human things that require redemption and restoration from the leaves of the tree of life. Humanity will be transformed into the likeness of Christ (2 Corinthian 3:18) and this statue is a raw intimation of that hope.

References

Apringius of Beja. 2011. ‘Explanation of the Revelation by the Most Learned Man, Apringius, Bishop of Pax (Julia)’, in Latin Commentaries of Revelation, Ancient Christian Texts, ed. by William C. Weinrich (Downers Grove: IVP Academic), pp. 23–63

Unknown artist :

A sheet from an Arabic manuscript on botany (Kitāb al-Durar wa-al-wuqūf ʻalá al-aʻyān wa-al-ṣuwar), 16th century , Illuminated manuscript

Pieter de Hooch :

Woman lacing her bodice beside a cradle, c.1660–63 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, Greece :

Head of Aphrodite, later carved with a cross, 1st century CE , Marble

Maranatha

Comparative commentary by Clementine Kane

The first six verses of Revelation 22 round out the vision of the heavenly city begun in the previous chapter. Added to the city’s immense architectural beauty is the wonder of nature in harmony; pure abundance in the form of a flowing river of life and the tree of life itself. It is a garden-city.

In the sixth century BCE, Ezekiel has a similar vision of his world restored and renewed. In it, trees watered by the river of life flowing from the temple bear fruit in each season and their leaves offer healing (Ezekiel 47). In John’s revelation, however, we are told something new: this tree has leaves which are for the healing of the nations. The heartbeat of salvation offered freely to all that begins in Genesis and pulses through the Gospels and Epistles is here reiterated in the shattering goodness of this tree that offers healing, not just for one nation or one affliction, but for all.

The oak leaf of the herbal manuscript chosen for this exhibition is part of the great tradition of herbal medicine. As such, it represents the physical healing that can take place in this life and foreshadows the effect of those health-giving leaves in the life to come. The manuscript itself, as a cooperation between cultures, is a foretaste of the unity in diversity of heaven, and the healing offered freely to all.

Whatever ills, wrongs, or violence the peoples of this earth—and their art—have suffered, restoration is offered in the streams of living water flowing from the throne of God. The marks which the goddess Aphrodite bears were perhaps intended to distinguish her from her old purpose and context and reassign her a new one. The decision to keep yet redefine the statue, instead of destroying it, acknowledges that there is something of human creativity and experience to keep, and sanctify, rather than abolish completely. It is a recognition that it is not ‘civilization/culture/the city itself that is evil, but the distortion of city/culture/civilization’ (Gorman 2011: 164).

These first six verses are more than an uplifting coda. As understood by centuries of Christian interpreters, ‘this vision—or rather, this coming reality—is the climax of the book of Revelation, the New Testament, the entire Bible, the whole story of God, and also the story of humanity’ (ibid 163). John’s description of the new heaven and the new earth affirms that this coming reality is intensely material. It will not occur solely in our minds or souls but in our transformed bodies and world as well. Gorman writes that ‘[t]his eschatological reality is not an escape from the materiality of existence but the very fulfilment of material existence…. Paradise, the original creation depicted in Genesis, has been restored, not abandoned or destroyed’ (ibid 164).

While it is a masterpiece of symbols and images, John’s revelation is at heart a pastoral letter written to a particular set of churches. One pastoral theme that emerges in the epilogue of the final chapter is that of living faithfully in joyful anticipation. The simplicity and calm beauty of Pieter de Hooch’s painting gives a sense of one way of living faithfully in joyful anticipation. Adela Yarbro Collins writes that:

[t]he destiny of the world and even of the church is beyond human control. But people can discern the outlines of that destiny and ally themselves with it. They can avoid working against it. And they can embody its values in witness to the world. (Collins 1979: 150)

John’s image of a world divided by who or what they choose to worship resolves itself into an invitation—‘come!’. Human responsibility is held in tension with the God who vows to make all things new. John’s revelation is not concerned to predict the day or the hour, or to delineate who is in and who is out. Instead, followers of Christ are called to heal as Christ healed, to be conformed ever more to the likeness of Christ until they see God face to face and his name is inscribed on their foreheads. In short, to live faithfully awaiting the unveiling of heaven on earth as those who are near the end of time. Let the righteous still pursue righteousness, let the holy become holy, let the farmers cultivate, the teachers guide, the parents nurture, the builders labour, the scientists explore, the pastors shepherd, the artists create. Maranatha—Come Lord!

References

Collins, Adela Yarbro. 1979. The Apocalypse (Collegeville: Liturgical Press)

Gorman, Michael J. 2011. Reading Revelation Responsibly (Eugene: Cascade Books)

Mommsen, Peter (ed.). 2022. Hope in Apocalypse: Plough Quarterly, 32 (Walden: Plough Publishing House)

Commentaries by Clementine Kane