Matthew 19:16–30; Mark 10:17–31; Luke 18:18–30

The Rich Young Man

George Frederick Watts

‘For he had great possessions’, 1894, Oil on canvas, 139.7 x 58.4 cm, Tate; N01632, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Mourning Lessons

Commentary by Charles A. Gillespie

George Frederic Watts captures the melancholy of his title, taken directly from Mark 10:22/ Matthew 19:22, ‘For he had great possessions’. He has, it seems, inherited material wealth; now he asks to inherit the kingdom of heaven. The painting provokes hard questions that walk beside this familiar story. Might the rich young man (or ruler in Luke) be wondering why his achievements—prestige, education, and virtue—should burden his pursuit of holiness?

Watts’s figure, with his slumped shoulders, might suggest to us a childlike sadness. Maybe too it awakens a theological realization: eternal life, the greatest possession, cannot be owned, or accomplished from our own resources. The man gazes downward, his shoulders weighted by fur trim and a golden chain. Only one hand emerges from the sumptuous fabric, poised ambiguously in a half-closed, half-open position. To give away favourite things feels like loss, perhaps even the anxious sacrifice of a longstanding identity in which much has been invested. Can this would-be disciple imagine himself apart from what he owns?

We never learn the rich man’s name in the Gospels; Watts, as though in keeping with this fact, hides his face from view. We know the subject of Watts’s portrait only from titles and garments: just those great possessions that Christ now asks him to give away. But what point in the story, exactly, has Watts shown us in this moment of apparent mourning? The spare background has a single vertical line to organize perspective with shadows near the bottom. Watts implies bare walls, possibly the corner of an empty room. We might imagine the narrator’s ‘he had great possessions’ describing the rich man’s sigh in preparation for an immediate estate sale.

Nevertheless, we know he is a quick learner. He corrects himself from ‘Good Master’ to ‘Master’ after only a single injunction from the Teacher (Mark 10:20). The painting invites us to grieve the difficulty of this next assignment, but also to hope that this nameless man will sell his great many things and join Jesus’s crowd of followers. His hand might not be clutching at all, but rather in the middle of the first intensely hard act of letting go.

Paul Klee

New Harmony, 1936, Oil on canvas, 93.6 x 66.3 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; 71.1960, © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY

Hearing Colours Newly Arranged

Commentary by Charles A. Gillespie

At first, Paul Klee’s New Harmony may appear rigidly four-square, but a closer inspection could lead us to notice imprecision in these ‘squares’. Can we imagine how the colours and shapes—interpreted by some as Klee’s response to musical theory—might undulate, dance, and play together? When Jesus enumerates familiar commandments, do they work like these discrete colours? What does it mean to keep all of the commandments?

Perhaps the rich young man (or ruler according to Luke) in this passage imagines God’s instructions as something like Klee’s patterns. Jesus rearranges the music of the law in a way that is analogous to the way our eyes might move about Klee’s painting. Harmony emerges in relation, not isolation.

Klee, too, might help us find the harmony in those words of Jesus that connect the rich man to the other disciples; all are addressed as ‘children’ (Mark 10:24). No one can win the inheritance of eternal life through their own isolated brilliance, zeal, or action.

The more memorable lesson of this passage may be about money, but the Gospel cautions against all sorts of self-centred focus. Jesus calls for a hard a way of keeping commandments—with a love suitable for building the kingdom of heaven rather than a concern with one’s own success. The rich man must learn to see and hear others; he must be harmonized in a new way. Peter and other disciples, too, must be wary of ‘owning’ their discipleship as though it were a clear-cut or finished work. Peter exclaims that the disciples have already met the terms of Jesus’s amazing request to the rich young man: ‘Lo, we have left everything and followed you’ (Mark 10:28; see also Luke 18:28; Matthew 19:27). Jesus replies with yet another inversion. Overconfidence in the eventual harmony of eternal life might refuse to see and respond to the interim dissonance of ‘persecutions’ (Mark 10:30).

Mark’s Gospel continuously rearranges what was already known. Its ‘good news’ takes us beyond the known, asking more of us than we are prepared for, and directing us to love what is beyond our habitual horizons. Do we know what keeping all of the commandments looks like? It might be more like listening between colours.

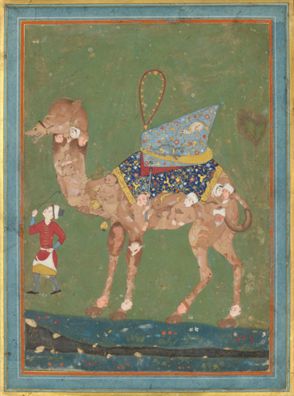

Unknown Iranian artist

Composite Camel with Attendant, Late 16th century, Opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 229 x 170 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of George D. Pratt, 1925, 25.83.6, www.metmuseum.org

Composing the Kingdom

Commentary by Charles A. Gillespie

This Composite Camel with Attendant represents an anonymous miniature manuscript illumination, potentially from late-sixteenth-century Iran. Lavish colours and textures are used to suggest the sky, ground, and cargo which frame its central subject, the camel, whose outline circumscribes a visual puzzle in browns and beiges.

Using a popular technique, perhaps an image of the oneness of all creatures in God, the camel consists of animals, fantastic beasts, and people of differing cultures. Caravans connected the world and its wealth through the profits of foreign trade and cultural exchange. Could we imagine this camel as a Silk Road stitched together? In talking about camels and eternal life (Mark 10:25; Matthew 19:24; Luke 18:25), Jesus adapts a well-known proverbial motif in which a big animal squeezing through a tiny space is used to suggest something impossible or surreal (Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 55b; Marcus 2009: 731, 736). The metaphor of the camel, needle, and entrance to the kingdom of heaven also appears in the Qur’an (al-A’rāf 7.40). Ideas and scriptural poetry spread by trade, as well as commodities. Does this image point us beyond the comforting boundaries we often impose on the Gospels?

This patchwork vision of a camel might also invite us to juxtapose Jesus’s challenge about the salvation of the rich in Mark with the camels of a Nativity scene: Matthew’s caravan of royal magi following a star. They were the first Gentiles to recognize Christ. Here too something new is stitched into the story, and again we may ask: what role will wisdoms from other cultures and traditions play along the way to eternal life?

‘Then who can be saved?’ (Mark 10:26; see also Matthew 19:25; Luke 18:26). Impossible combinations may also be scary and unsettling—not unlike Jesus’s promised ‘persecutions’ (Mark 10:30). This multiplex camel has a single attendant, but his identity too is ambiguous. We may imagine him as a figure for Christ, for the rich young man, for us who ‘attend’ to the story and each other.

The least expected are suddenly revealed as first (Mark 10:31). Perhaps the ‘hundredfold’ gifts in the ‘age to come’ will arrive like a composite kingdom (Mark 10:30): a quilted-camel greater than the sum of its parts. Perhaps this paradoxical composite camel—monks and lovers, demons and dogs, rabbit-hooves and fox-tails—suggests, in one moment, the whole of Creation’s long caravan toward God.

References

Marcus, Joel. 2009. Mark 8–16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New Haven: Yale University Press)

George Frederick Watts :

‘For he had great possessions’, 1894 , Oil on canvas

Paul Klee :

New Harmony, 1936 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Iranian artist :

Composite Camel with Attendant, Late 16th century , Opaque watercolor and ink on paper

Visualizing Impossibility

Comparative commentary by Charles A. Gillespie

How does impossibility look to the eye? We call events or ideas ‘impossible’ when they show us something unexpected, inexplicable, or suddenly new. The sort of impossibility perhaps imagined by George Frederic Watts’s portrait of a rich man faced with a challenge harder than anyone would want a challenge to be. These are the possible ‘impossibilities’: undoable only because they have yet to be done. Improbable and potentially inadvisable; but technically ‘possible’ according to the rules of the everyday, waking world. Even though the task is ‘impossibly difficult’, anyone could sell everything and follow Jesus. Peter reminds his master how some already have!

Those disciples must then react to another impossible image. Jesus’s micro-parable says big camels go through tiny needles more easily than rich people enter the kingdom of heaven. Impossibility can also be seen through the surreal. This is the impossibility at work in the Composite Camel with Attendant: a beast unable to be found in the wild world as we know it. Imagined impossibilities can even be frightening. Beautiful and strange, this camel may shock, amaze, or captivate—like Jesus’s challenge to the rich young man (or ruler in Luke). If it only shocks it leaves us like Watts’s rich aristocrat. If it also captivates it encourages us to journey. Sometimes, artists visualize impossibility by reassembling pieces of the world as we know them. Monsters and fantasy vistas expand the limits of the imagination, pointing to the world’s promise beyond ordinary sightlines.

Some impossibilities will never literally be ‘seen’ in a picture. Words of poetry can sing logical contradictions (like a square circle) in ways that elude figurative art’s representational forms. Yet the abstract colours and shapes in Paul Klee’s palette could perhaps be said to rhyme with this third sort of impossibility. Does New Harmony elicit the same calm feeling of balance as a well-struck chord, connecting us with something more than what we see?

Themes of recombination and renunciation are a feature not just of this exchange with the rich young man, but of the teachings and encounters that immediately precede and follow it. They are reminders of how accepted standards of possibility become transfigured in God. Christ’s teaching about inheritance, goodness, and salvation all underscore God’s complete unexpectedness. Only God counts as good (Mark 10:18; Matthew 19:17; Luke 18:19); only ephemeral treasures in heaven have lasting value (Mark 10:21; Matthew 19:21; Luke 18:22); all things are possible only for God (Mark 10:27; Matthew 19:26; Luke 18:27). These three images invite us to consider impossibility: the non-possibility for mortals of achieving eternal life through some action of their own. The impossible coherence of all the world’s history living eternally in the kingdom of heaven: a complex-unity beyond the confines of the world’s old and broken harmonies of time and space. New Harmony could, perhaps, work alongside the Composite Camel to awaken in us a new sensibility about the heavenly kingdom.

The viewer of a work of art assembles differences into unity by operating from outside an image’s ‘frame’. The rich young man is asked to adopt a viewpoint that permits a new assemblage of what he sees—perhaps to look on the poor with the same gaze of love he receives from Christ.

We might view in the camel’s single attendant a reminder of this Christ: the One who invites the rich man to ‘come, follow me’ (Mark 10:21; Matthew 19:21; Luke 18:22) just as the other disciples have already done. The caravan leads to eternal life by following behind the teacher, turning away from self-obsessed histories toward shared futures.

Reading in the company of these works of art may help us to visualize the astounding wonders of God. The impossibilities suggested by them remind us of the vast treasures the follower of Christ has already inherited, precisely while being asked to give them away. Beauty arises when goods are shared.

These works critique cultures of opulence even as they participate within them. Hoarded wealth, like any self-obsession, curves our attention inwards and causes us to look away from the amazements that arise from sharing in unexpected relationships. Like these images, Christ directs our attention outside comfortable frames of reference. Perhaps Watts’s sense of avarice’s lament honours the grace required to do an impossible act of love for others. The Composite Camel may help us glimpse the impossible harmonization of histories in the eternal life promised by Jesus. Klee’s abstractions can invite new openness to wonder through artistic experiments that push the limits of what was previously thought possible.

These works remind us that God’s all-possibility always confounds and reshapes the merely mortal imagination.

Commentaries by Charles A. Gillespie