Genesis 38

Tamar

Leon Mostovoy

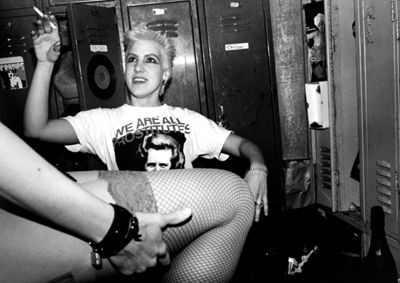

We Are All Prostitutes, from the 'Market Street Cinema' series, 1988, B&W Archival fiber print, 50.8 x 60.96 cm; © Leon Mostovoy; Photo courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Taking Destiny Into One’s Own Hands

Commentary by Marika Rose

This photograph of lesbian sex workers back stage at a San Francisco strip club is taken from Leon Mostovoy’s series Market Street Cinema. Mostovoy was a key contributor to the magazine On Our Backs, which played an important role in the feminist ‘sex wars’ of the 1980s, where deep disagreements about the value of sex work and pornography in queer and feminist liberation divided the movement (Guy 2016).

For many at this time, San Francisco represented a utopian space of possibility and freedom. The unfolding AIDS crisis highlighted the contrast between the relative freedom of San Francisco and the fearful hostility of mainstream society, as many people responded to the frightening spread of an unknown new disease by blaming and stigmatizing queer people. Mostovoy said that in this series he hoped to depict ‘a strong group of femmes … using the sex industry as a way of accessing power, control and money’ (ONE 2015).

Tamar, in her context, did not take up 'sex work' freely or without danger: she narrowly escaped a fiery death at the hands of her hypocritically puritanical father-in-law. But only when she left the safety of her respectable family home to engage in risky sexual behaviour did she gain the freedom to act and to determine her destiny for herself. In the biblical account, once Tamar has returned to respectability—giving birth to twin sons and thus ridding herself of the stigma of sexual immorality—she disappears into the background of the text, no longer referred to by name.

But her story of cunning remains, reminding us of the thin line between respectability and social ostracism, suggesting that it is not always unconventional sexual behaviour but sometimes the violent policing of sexual purity that puts vulnerable people most at risk, and hinting that certain possibilities may only be found at the margins of society.

References

Guy, Laura. 2016. ‘Sex Wars, Revisited’, Aperture 225: 54–59

ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. 2015. Leon Mostovoy: Market Street Cinema, available at: https://one.usc.edu/exhibition/leon-mostovoy-market-street-cinema

Emile Jean Horace Vernet

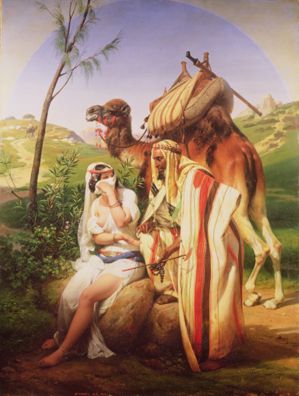

Judah and Tamar, 1840, Oil on canvas, 129 x 97.5 cm, The Wallace Collection, London; P346, Bridgeman Images

Double Standards

Commentary by Marika Rose

In Horace Vernet’s Tamar, a dark-skinned Judah leans threateningly over a light-skinned Tamar. Tamar’s bare breast and thigh indicate the fact that she is in the act of selling her sexual services, while her veil suggests the mysterious and alluring sexuality which nineteenth century Orientalists like Vernet associated with ‘Eastern’ women (Said 1979: 182).

Judah’s and Tamar’s clothes are based on Vernet’s careful studies of Egyptian clothing. In the desert landscape behind them there is no sign of the rapid processes of modernization and conflict driven by European colonization which were then reshaping the country. Together, clothes and background present an image of Egypt as an ancient but static culture, unchanged since biblical times (Hannoosh 2016: 430).

Biblical texts frequently use the imagery of women’s bodies to signify the purity and fertility of unconquered land, and this biblical imagery played an important role in the way nineteenth-century European colonizers understood themselves. The soft vulnerability of Tamar’s exposed body suggests the opportunity and fertility which European Christians saw in (what they took to be) the pure, untouched lands of North Africa (Schaub 2017: 75; Meyer 2017: 249).

Yet despite the violence unfolding in Egypt as a direct result of European colonialism, here the threatening masculine figure is portrayed not as European, but as Egyptian. The hypocrisy of Judah—happy to ask a friend to take payment to the sex worker that he visited, yet so horrified at the prospect of Tamar’s ‘whoring’ that he threatened to burn her to death—is a hypocrisy shared by Vernet’s depiction, which both revels in Tamar’s seductively exposed body and positions her as threatened by the dark-skinned man who looms over her.

The idea that North African men posed a threat to the women of their societies played a key role in European justifications both for colonialism—seen as the best way to free women from patriarchal control—and for restrictive laws attempting to control sex workers’ behaviour in the name of protecting their virtue (Zonana 1993; Ware 2015; Doezema 2013). But those women were never merely passive victims. We can glimpse Tamar’s cunning here in the staff Judah hands her in lieu of payment—the staff she will later use to prove that he is the father of her illegitimate child. So too the history of resistance to colonialism is full of stories of clever, resourceful women, finding ways to protect themselves and those they loved.

References

Doezema, Jo. 2013. Sex Slaves and Discourse Masters: The Construction of Trafficking (London: Zed Books)

Hannoosh, Michèle. 2016. ‘Horace Vernet’s “Orient”: Photography and the Eastern Mediterranean in 1839, part II: the daguerreotypes and their texts’, The Burlington Magazine, 148: 430–39

Meyer, Andrea. 2017. ‘A View from Germany: Vernet, New Media, and the Remaking of History Painting’, in Horace Vernet and the Thresholds of Nineteenth Century Visual Culture, ed. by Daniel Harkett and Katie Hornstein (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press), pp. 245–62

Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books)

Schaub, Nicolas. 2017. ‘Horace Vernet and the Conquest of Algeria through Images in Horace Vernet and the Thresholds of Nineteenth Century Visual Culture, ed. by Daniel Harkett and Katie Hornstein (Hanover: Dartmouth College Press), pp. 73–89

Ware, Vron. 2015. Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism, and History (London: Verso)

Zonana, Joyce. 1993. ‘The Sultan and the Slave: Feminist Orientalism and the Structure of Jane Eyre’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 18.3: 592–617

Juniper Fleming

Mother and Child, 2014, Silver gelatin print, oil paint, 48.26 x 76.2 cm, Collection of the artist; © Juniper Fleming; photo: Courtesy of the artist

Untold Roles

Commentary by Marika Rose

In Juniper Fleming’s photograph, a small girl feeds cherries to her mother, who lounges against an opulent background. The photograph is a contemporary reimagining of Frederic Leighton’s 1865 painting Mother and Child (Cherries) (Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery).

The work that Leighton was producing in the 1860s played an important role in contemporary debates about the nature and value of art and aesthetic pleasure. Critics disagreed about whether his depictions of quiet, seemingly aimless moments represented a triumph of artistic skill and beauty or a troublingly amoral and dangerously lazy celebration of doing nothing.

These discussions do not appear to have considered the work being done in Leighton’s paintings by his models (Prettejohn 1996).

The series of photographs by Fleming from which this work is taken, Reclamation and Dis/Atonement, recreates canonical Western depictions of women. Fleming worked with her models—who were sex workers like Fleming herself—to highlight the often hidden role played by sex workers—as models and muses—in creating Western ideals of feminine beauty.

Biblical narratives of ‘sexually deviant’ women such as Tamar often express anxiety about the transmission of inheritance from father to son. Biblical and contemporary worries about women’s sexual purity cannot be disentangled from a patriarchal logic of paternal inheritance. In taking her fate into her own hands and risking her life to secure property—first Judah’s staff and seal and then his sons—Tamar makes herself, however briefly, the centre of her own world, the agent of her own destiny. In this, she is like Fleming, who writes: ‘The world made me a sex worker, but sex work is also how I make the world’ (Fleming).

The poet and scholar of Jewish thought Ruth Kaniel sees Tamar’s story as part of a lineage of sexually transgressive ‘mothers of the messiah’ which runs throughout the Hebrew Bible, beginning with the incestuous daughters of Lot and culminating redemptively in the story of Ruth, whose love for Naomi gives us an image of love and care between women (Kaniel 2017). The scriptural text never shows Tamar interacting with other women, but perhaps Fleming’s image allows us an imaginary glimpse behind the scenes of the story.

References

Fleming, Juniper. n.d. ‘Reclamation and (Dis)atonement’, available at: http://juniperfleming.com/reclamationgallery.html [accessed 22 April 2021]

Kaniel, Ruth Kara-Ivanov. 2017. Holiness and Transgression: Mothers of the Messiah in the Jewish Myth (Boston: Academic Studies Press)

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. 1996. ‘Morality Versus Aesthetics in Critical Interpretations of Frederic Leighton 1855–75’, The Burlington Magazine, 138: 79–86

Leon Mostovoy :

We Are All Prostitutes, from the 'Market Street Cinema' series, 1988 , B&W Archival fiber print

Emile Jean Horace Vernet :

Judah and Tamar, 1840 , Oil on canvas

Juniper Fleming :

Mother and Child, 2014 , Silver gelatin print, oil paint

No Fairytale

Comparative commentary by Marika Rose

At the end of this story, Tamar is restored to righteousness, to respectability, to her place in the family, and to a bit part in the long biblical story of fathers passing things down to their sons. Although her actions deviate from the normal path of biblical wives and mothers, nevertheless—like them—her main purpose seems ultimately to be fulfilled in ensuring that the father has a son to inherit his name and his property. The birth of Tamar’s children is the last we hear of her. With that, her adventures are over.

It’s easy to forget the moment when Judah threatens to burn Tamar to death, just as it was easy for Horace Vernet to leave the invading colonial armies out of his romantic depiction of Tamar as a nineteenth-century Egyptian. Yet Tamar’s story allows an attentive reader to catch a glimpse, fleetingly, of the violence which hovers in the background of the production of happy endings and good wives and mothers. It allows us a brief insight into the difficult and dangerous work which goes into making ‘happy families’—just as Juniper Fleming’s reimagining of Frederic Leighton’s Mother and Child (Cherries) brings into view the work that women do as artists’ models, and the role that sex workers may have played in producing our idea of what beautiful females and chaste wives look like. Moreover, Tamar’s example may lead us to conclude that sometimes there may be more freedom for people who are outcasts than for people who play by the rules—just as Leon Mostovoy’s photograph reminds us of the bonds of affection, the courage, and the solidarity there can be among sexual deviants and gender outlaws.

In Tamar’s story we are offered a glimpse of the costs that can be exacted when societies advance certain ideals of 'the family', and we are provoked to reflect on how the narratives we tell about our identity as members of a nation, a religious community, or a family can put others at risk.

Tamar does difficult, dangerous (v.24), and scandalous 'work' in order to ensure her future, even though it is principally because she becomes a mother and returns to the propriety of the family that she is considered righteous. In this way, she secures for herself a position of honour and importance in her family and community, even though her cleverness means that the father of her twins—the man who threatened to have her killed—gets to pass his property on to his sons. They in turn will continue the long line of fathers passing on property to their sons, while leaving Tamar’s female descendants just as dependent as she was.

Tamar is a foreigner—Judah has left his brothers to live among Canaanites (38:1–2)—even though in the larger narrative frame within which her story is preserved what is most important about her is that she makes it possible for the people of God to carry on reproducing themselves, and eventually to conquer the land which belongs to her people.

Brave and cunning, Tamar is (however briefly) the protagonist of her story. She takes risks, acts against tradition, and transgresses the boundaries which the people around her believe in between good and bad behaviour, between pure and impure sexuality.

Perhaps Tamar can help us to think about what it means to inherit traditions that like to tell stories about sexual, racial, or national purity. The biblical story, like the heterosexual family or the European nation, is not as simple as we sometimes pretend. It is messier, less respectable, and nowhere near as pure as the glosses we put on it.

Reading the Bible along with Tamar can help us to think about how to negotiate religious traditions that are sometimes deadly and always dangerous; it can help us to ask what it means to inherit violent histories of racism, sexism, and property, and to try to take care of one another without handing that violence down to the next generation. Tamar’s story can help us to think about the immense amounts of work that go into reading and handing on texts and traditions, and the moments of freedom which can sometimes come when we refuse to play by the rules, suspend our concerns about sexual purity, and insist on taking care of the people who aren’t supposed to be important.

Commentaries by Marika Rose