Genesis 39

Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife

Unknown French artist [Paris]

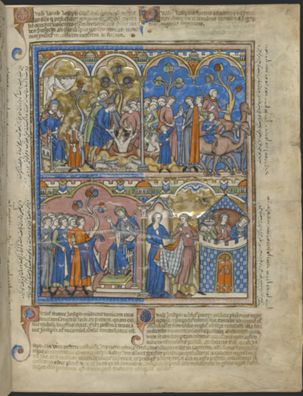

Joseph Sold into Slavery, Bad Blood, False Accusations and Portents of the Future, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54, Illumination on vellum, 390 x 300 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J.P. Morgan (1867–1943) in 1916, MS M.638, fol. 5r, Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Crown Control

Commentary by Richard Leson

Beneath a delicate trefoil arch that signifies her chambers, the wife of ‘Potiphar, an officer of Pharaoh, the captain of the guard’ (Genesis 39:1 NRSV), grabs hold of the mantle of Joseph’s vair-lined mantle as he attempts to flee her advances.

This picture is a detail—at the lower right of the sheet—of a miniature in the mid-thirteenth century French codex named the ‘Morgan Picture Bible’ or, on account of its many biblical battle scenes, the ‘Crusader Bible’. The Picture Bible’s numerous illustrations lacked explanatory inscriptions until the fourteenth century, when an Italian scribe added captions in Latin. Following the presentation of the manuscript to Shah Abbas of Iran (1588–1629), a second scribe added further captions in Persian. Finally, in the seventeenth century, a Hebrew scribe penned a final set in Judeo-Persian.

In keeping with pastoral strategies for lay instruction, the miniature attends to the literal sense of the biblical text. But for the earliest audiences of the manuscript, the salient themes of the Joseph story—familial betrayal, intrigue, and family reunion—also reverberated with tastes in romantic literature. Vernacular versions of the Joseph story proliferated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries—popular retellings that amount to ‘scripture-as-romance’ (Gauthier-Walter 2003: 299–305).

Close scrutiny of the miniature reveals a portion of the faint under-drawing, still visible through the paint: originally, the would-be seductress wore a crown. The obscured crown agrees with vernacular retellings of Genesis 39 in which Joseph is propositioned not by the wife of Potiphar but rather the queen-consort of Pharaoh himself, a promotion that intensifies the scandal and more forcefully invites comparison to the stuff of courtly romance.

Was this ‘cover-up’ of the crown a conscious editorial decision akin to a scribe correcting a biblical text? If so, it may evince some clerical discomfort with the burgeoning industry of popularized Scripture. The first of the three sets of captions eventually added to this Picture Bible was written in Latin, in contrast to the vernacular legends, and unambiguously insists that the woman in the illumination is wife to ‘Pharaoh’s captain of the guard’ (Weiss 1999: 331).

The later Persian captions, however, evince a popular sensibility akin to that signified by the crown. The woman is identified as ‘Zulaikha’—the name of Potiphar’s wife in medieval Islamic retellings of the Qur’anic account of Yusuf. The story’s enticing extracanonical embellishments reassert themselves.

References

Gauthier-Walter, Marie-Dominique. 2003. L’Histoire de Joseph. Les fondements d’une iconographie et son développement dans l’art monumental francais du XIIIe siècle (Bern: Peter Lang)

Hourihane, Colum (ed.). 2005. Between the Picture and the Word: Manuscript Studies from the Index of Christian Art (University Park, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Migne, Jacques-Paul. 1844–80. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Latina, 221 vols (Paris)

Noel, William, and Daniel H. Weiss (eds.). 2002. The Book of Kings: Art, War, and the Morgan Library’s Medieval Picture Bible (Baltimore: Third Millennium)

Weiss, Daniel H., et al. 1999. The Morgan Crusader Bible Commentary (Luzern: Faksimile Verlag)

Unknown Bukharan artist

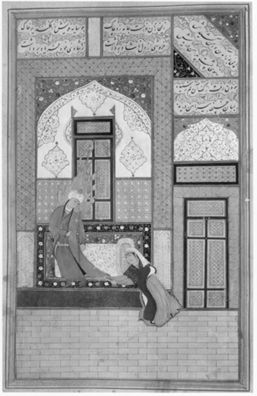

Zulaykha Seizing the Skirt of Yusuf's Robe, from a Yusuf and Zulaykha of Jami, 1523–24, Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper, Painting: 210 x 121 mm; Page: 270 x 173 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Alexander Smith Cochran, 1913, 13.228.5.4, www.metmuseum.org

A Palace of Persuasion

Commentary by Richard Leson

The Qur’an’s version of Genesis 39:1–23 is found in its twelfth Surah (chapter), which tells how the Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) was sold into the house of an Egyptian whose wife sought to seduce him. In keeping with some rabbinic commentary, the early Islamic exegete Tabari (d.923) acknowledged that Yusuf was tempted by Zulaykha (Brinner 1987: 155–60) but held that God intervened to save him from adultery.

Curiosity about the romantic undertones of the tale, which the Qur’an itself (Yusuf 12:3) calls ‘the best of stories’, gave rise to a tradition of scriptural commentary and poetry that spanned the medieval Islamic world. It is this tradition that gave the would-be-seductress a name: Zulaykha. By far the best-known version of the tale is the epic romance Yūsuf u Zulaykhā, composed 889/1484–5 by the Persian poet and mystic Jami (Pendlebury 1980; Simpson 1997: 116, 330). According to Jami, Zulaykha’s desire for Yusuf is an allegory for the soul’s search for the divine but, in keeping with prominent themes in Sufi Islam, the poem’s heady mixture of romantic and mystical love allowed for both literal and spiritual interpretations (Merguerian and Najmabadi 1997: 497–500).

Yusuf and Zulaykha was the most popular of the seven books of Jami’s Haft Awrang (Seven Thrones), as well as the most frequently illustrated throughout the Islamic world. This miniature, from a manuscript attributed to Bukhara—now in modern Uzbekistan (Simpson 1997: 330, 371)—shows Zulaykha’s attempt to prevent Yusuf, whose head is surrounded by a flaming nimbus, from fleeing her advances. The setting is an ornate palace she has constructed for the express purpose of Yusuf’s seduction.

In this she is almost successful. According to Jami, Yusuf is on the verge of surrendering to Zulaykha when he notices her discreet attempt to cover her nearby idol. He is reminded of Allah and flees. Rather than illustrate the idol, the miniaturist concentrated on the moment that Yusuf pulls away.

The encounter of Yusuf and Zulaykha resembles numerous depictions of the encounter between Joseph and Potiphar’s wife in Jewish and Christian art, proof of the composition’s poignancy regardless of confessional or narrative context.

References

Brinner, William M. (trans.). 1987. The History of al-Tabarī, vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs (Albany, NY: State University of New York)

Merguerian, Gayane Karen, and Afsaneh Najmabadi. 1997. ‘Zulaykha and Yusuf: Whose “best Story”?’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 29.4: 485–508

Pendlebury, David (ed. and trans.) 1980. Yusuf and Zulaikha: An Allegorical Romance by Hakim Nuruddin Abdurrahman Jami (London: Octagon)

Simpson, Marianna Shreve. 1997. Sultan Ibrahim Mirza’s Haft Awrang: A Princely Manuscript from Sixteenth-Century Iran (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Unknown artist

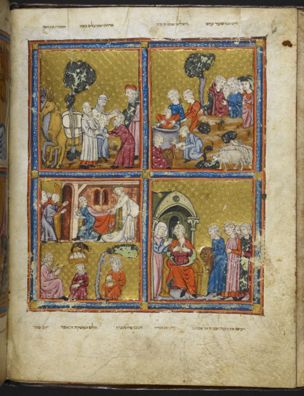

Joseph and Potiphar's Wife and Scenes from the life of Joseph, from the Golden Haggadah, c.1320–30, Illuminated manuscript, 245 x 190/200 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 27210, fol. 6v, © The British Library Board

Royal Repose

Commentary by Richard Leson

As he rushes from her bedchamber, Joseph turns back to admonish the wife of Potiphar. He points to the heavens, in keeping with his protest: ‘Now how can I commit this great evil, and sin against God?’ (Genesis 39:9 NRSV). But he is already undone: the household has arrived in response to her cry: ‘Look! … He came to me to lie with me’ (v.14).

This miniature is found at the lower left of a folio in the Golden Haggadah, an opulent Sephardic manuscript made in Catalonia around 1320–30 (Narkiss 1970). Exceptionally for a haggadot manuscript, the Golden Haggadah prefaces the traditional texts for the Passover Seder with no less than fifty-six biblical miniatures based on Genesis and Exodus. Its rich, gold-tooled backgrounds, rectangular miniature frameworks, and iconography have led to comparisons with Christian book illumination, particularly with the mid-thirteenth century Morgan Picture Bible (elsewhere in this exhibition).

That Potiphar's wife here lies abed suggests the painter’s familiarity with the Jewish commentary tradition, which pondered why ‘… on a certain day … none of the people of the house were there in the house.’ (Genesis 39:11). The rabbis’ solution was that Potiphar and his household were attending an Egyptian religious festival and that, sensing an opportunity to seduce Joseph, Potiphar’s wife feigned illness and invited Joseph to lie down next to her (Carasik 2018: 349).

The bed motif is rare in Christian art of the later Middle Ages (it is absent, for example, in the Morgan Picture Bible), though it would become standard in later Renaissance and baroque works. Another iconographic element of the Golden Haggadah illumination does, however, suggest a debt to Christian iconographic motifs. The crown worn by Potiphar’s wife agrees with rhymed biblical paraphrases of Genesis 39 in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century France and England, composed in the vernacular for the Christian laity. In these popular retellings, the enslaved Joseph serves Pharaoh directly and is accused by no less than the queen of Egypt.

For the Jewish audiences of the Golden Haggadah—who were by law the property of the Christian Catalan ruler—the crown may have summoned to mind their complicated relationships with non-Jews. Ironically, similar concerns preoccupied rabbinic exegetes of the episode, for whom the Egyptian femme-fatale’s attempted seduction of Joseph held out the worrisome possibility of a rupture of confessional boundaries and a loss of cultural integrity (Carasik 2018: 348–40; Levinson 1997).

References

Carasik, Michael (ed. and trans.). 2018. The Commentator’s Bible: Genesis: The Rubin JPS Miqra’ot Gedolot (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society)

Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2006. Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain: Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press)

Levinson, Joshua. 1997. ‘An-other Woman: Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife. Staging the Body Politic’, The Jewish Quarterly Review, 87.3: 269–301

Narkiss, Bezalel (ed.). 1970. The Golden Haggadah: A Fourteenth-Century Illuminated Hebrew Manuscript in the British Museum (London: Eugrammia)

Unknown French artist [Paris] :

Joseph Sold into Slavery, Bad Blood, False Accusations and Portents of the Future, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54 , Illumination on vellum

Unknown Bukharan artist :

Zulaykha Seizing the Skirt of Yusuf's Robe, from a Yusuf and Zulaykha of Jami, 1523–24 , Ink, opaque watercolour, and gold on paper

Unknown artist :

Joseph and Potiphar's Wife and Scenes from the life of Joseph, from the Golden Haggadah, c.1320–30 , Illuminated manuscript

Romancing Joseph

Comparative commentary by Richard Leson

Late medieval images of Joseph propositioned by Potiphar’s wife are strikingly similar across Christian, Jewish, and Islamic art, a phenomenon that resulted from cultural exchange but more broadly from a shared interest in the subject’s palpable theme of adultery.

For the most part, Christian exegetes of Genesis 39:1–18 avoided allegorizing the episode in favour of straightforward moralization (Murdoch 2003: 166). This approach was not far removed from that of rabbinic commentators who praised Joseph’s chastity and good faith (Carasik 2018: 349) and early Qur’anic interpreters who argued that God intervened to save Yusuf (Joseph) from temptation (Brinner 1987: 155–60).

While indebted to this moralizing approach, the three late-medieval examples gathered here also suggest how popular tastes reshaped the story. Regardless of the religious context, the image of Joseph attempting to flee his would-be seductress satisfied shared appetites for suspenseful tales of desire and seduction. This is Scripture as romance.

In the thirteenth-century Morgan Picture Bible, the under-drawing of Potiphar’s wife wearing a crown betrays a familiarity with an alternative, Old French version of Genesis 39:1–18, in which Joseph is propositioned not by the wife of Pharaoh’s captain but rather the queen of Egypt. This transformation agrees with vernacular retellings that resituated the episode in the house of Pharaoh himself. For thirteenth-century audiences, the prospect of royal adultery placed the biblical material in conversation with the affairs of Lancelot and Guinevere or Tristan and Iseult.

The full-page miniatures of the fourteenth-century Golden Haggadah are clearly inspired by a Christian source like the Morgan Picture Bible, but here the action proceeds from right to left, in accordance with the Hebrew language. Remarkably, Joseph is once again propositioned by the wife of Pharaoh, as proven by her crown. While it is unclear how familiar Jewish audiences were with the Christian origins of this particular motif, its presence points to their general appreciation of the entertaining qualities of such imagery. For their part, the illuminators of the Haggadah enriched the Christian source material through the addition of the bed, a motif perhaps indebted to rabbinic questions about the precise circumstances of the attempted seduction but one that also amplified the sexual connotations.

Islamic audiences were equally intrigued by images of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife but understood the episode in terms of their own scriptural and literary traditions. The Qur’anic account of the life of Yusuf (Joseph) similarly places him in the house of an Egyptian whose wife seeks to seduce the prophet. Much as it had in Christian Europe, this tale fired the romantic imagination and gave rise to multiple poetic adaptations. Most famous of these is the Persian verse romance Yusuf u Zulaykha (889/1484–85) written by the Sufi mystic and poet Jami. In the final example gathered here, Zulaykha grasps the mantle of the fleeing Yusuf, a composition reminiscent of earlier Christian and Jewish miniatures that convey a similar amorous tension. Yet despite these romantic connotations the poet insists that Zulaykha’s love for Yusuf is, in fact, allegorical. In keeping with themes in Sufi Islam, the tale figures the soul’s desire for union with the divine.

References

Brinner, William M. (trans.). 1987. The History of al-Tabarī, vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs (Albany, NY: State University of New York)

Carasik, Michael (ed. and trans.). 2018. The Commentator’s Bible: Genesis: The Rubin JPS Miqra’ot Gedolot (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society)

Murdoch, Brian. 2003. The Medieval Popular Bible: Expansions of Genesis in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer)

Commentaries by Richard Leson