Genesis 41

Joseph’s Rise to Power

Peter von Cornelius

Joseph interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams, 1816, Watercolour and gouache over pencil on brownish card, 38.6 x 35.7 cm, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; SZ Cornelius 20, Alinari / Art Resource, NY

A Discerning and Wise Man

Commentary by Susan Docherty

Peter von Cornelius belonged to the Brotherhood of St Luke, a band of German Christian and Romantic artists who were part of a larger group called the ‘Nazarenes’. Inspired by Italian Renaissance painters such as Raphael, they sought a return to the artistic forms and religious subjects of the pre-Enlightenment era (Grewe 2005: 43). This watercolour is a preparatory study (dated to 1816) for one of a cycle of large-scale frescoes showing scenes from the life of Joseph. The frescoes themselves were made for a hall of the Palazzo Zuccari in Rome (and subsequently removed to the National Gallery in Berlin in 1887). They seem to have been partly modelled on the decorations of the Sistine chapel.

In the foreground, with his back to the viewer, Joseph stands before Pharaoh, explaining to him the meaning of his dreams. The court attendants, who have been unable to explain these visions, listen to Joseph with silent and rapt attention, as befits a man of such wisdom and discernment, ‘in whom is the spirit of God’ (Genesis 41:38–39).

The insignia of kingly office (the sceptre and the crown) and the grand throne (surmounted by its niche and pediment) project confidence and power, yet these contrast sharply with Pharaoh’s deeply worried countenance (v.8). This suggests his awareness of the potential impact of his troubling dreams on the welfare of all his people (Westermann 1996: 46). This focus on Pharaoh’s economic concerns is reinforced by other details in the painting. We are given glimpses of the current fertility of the land through the arches in the lunette above him, for instance, and decorating the lunette itself, we see symbols of the ‘plenty’ that Egypt will initially (but only temporarily) continue to enjoy (v.29): baskets of fruit and a nursing woman.

It is not clear from the biblical text how far Joseph is actively seeking the position of chief overseer which he proposes to Pharaoh after interpreting his dreams (vv.33–36; Turner 2009: 181). However, his immediate assumption of this role is signalled in the scene at the right of the painting in which he appears in his grand chariot (v.43). This not only offers a route out of anxiety for Pharaoh, but also secures Joseph’s future: ‘You shall be over my house, and all my people shall order themselves as you command; only as regards the throne will I be greater than you’ (v.40).

References

Grewe, Cordula. 2005. ‘Re-Enchantment as Artistic Practice: Strategies of Emulation in German Romantic Art and Theory’, New German Critique, 94: 36–71

Turner, Laurence A. 2009. Genesis, 2nd edn. (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press)

Westermann, Claus. 1996. Joseph: Studies of the Joseph Stories in Genesis (Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

Hilaire Pader

The Triumph of Joseph, 1657, Oil on canvas, 275 x 775 cm, Cathédrale Saint-Étienne, Toulouse; (CC BY-SA 4.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=48178134

Lord of the Land

Commentary by Susan Docherty

This is one of three biblical scenes painted by the Toulouse-born artist Hilaire Pader in 1657 for the city’s cathedral of St Stephen. It hangs on the left side of the transept, underneath the organ.

The horizontal orientation of this long frieze works well to present the majesty and grandeur of Joseph’s office of vizier in Egypt. The painting is characterized by sumptuous colours, which stand out vividly even within the dark interior of its cathedral setting. The inclusion of such a large crowd of people in different styles of dress and from diverse backgrounds emphasizes the extent of Joseph’s influence over the whole country (41:43–46) and indeed over the entire world. The artist is, therefore, accurately showing how ‘all the earth came to Egypt to Joseph to buy grain, because the famine was severe over all the earth’ (v.57).

Joseph is seated in a gilded chariot, dressed in a rich robe, with the typically Egyptian symbols of his lordly status—a crown, golden necklace, and ring—clearly visible (de Vaux 1978: 299). The artist courted controversy by attributing some of his own facial features to his handsome and relatively youthful hero (Lestrade 2010: 8).

Joseph is preceded on his triumphant tour of the country by heralds who announce him with a cry of ‘abrek’ (41:43). The original meaning of this term is uncertain. It is probably an Egyptian loan-word, and is variously translated as ‘kneel’, or ‘attention’ (Vergote 2016: 135–37). Pader perhaps interprets it in the latter sense, since the bystanders are not doing obeisance before the chariot. The population of Egypt are represented, then, as submitting to the authority vested in Joseph (v.40), but the expressions on their faces suggest that they greet his passing with joy and gratitude rather than from a sense of duty or fear. This is a fitting reception for the man who has been inspired by God to ensure that ‘the land may not perish through the famine’ (v.36).

References

Lestrade, Jean. 2010. Le Triomphe de Joseph et Le Deluge (Whitefish: Kessinger)

Trouvé, Stéphanie. 2016. ‘Lomazzo and France: Hilaire Pader’s Translation: Theoretical and Artistic Issues’, available at https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01319315v3

de Vaux, Roland. 1978. The Early History of Israel, vol. 1 (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd)

Vergote, Jozef. 1959. Joseph en Égypte (Louvain: Publications Universitaires)

Unknown artist

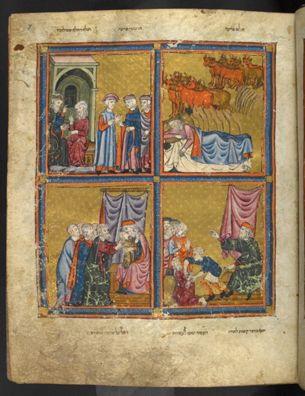

Scenes from the life of Joseph, from the Golden Haggadah (upper right: Pharaoh's dream; upper left: Joseph interpreting Pharaoh's dream; lower right: the arrest of Simeon; lower left: Joseph revealing himself to his brothers), c.1320–30, Illuminated manuscript, 245 x 190/195 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 27210, fol. 7r, © The British Library Board (Add MS 27210, fol. 7r)

Pharaoh’s Troubling Dreams

Commentary by Susan Docherty

When Jews retell the story of the exodus at the annual family Passover meal, they use a special service book called a Haggadah (named from the Hebrew verb ‘to tell’). This particularly beautiful and ornate example was produced in Catalonia around the year 1320 (Narkiss 1970: 56). It contains fifty-six miniature paintings of biblical scenes, all decorated with opulent gold leaf and intricate punchwork.

This folio represents the section of the Joseph narrative recounted in Genesis 41–43. As with all Hebrew texts, it is read from right to left, beginning in the upper register. The first panel depicts Pharaoh’s two dreams, then Joseph’s explanation of them. Both dreams, of cows and ears of grain (Genesis 41:1–7), are combined within the first miniature. This reflects Joseph’s interpretation that they share a single meaning (v.25). Cows were associated with fertility in ancient Egyptian thought, as well as serving as an essential source of food and labour (Brewer 1994). The dreams therefore presage a serious threat to the kingdom’s economy and prosperity, and so greatly trouble Pharaoh (v.8).

In the top left panel, Joseph is seated next to the ruler, in intimate discussion with him. Their heads are leaning towards one another, and the positions of their hands indicate an animated conversation. All the other courtiers stand a little way off, separated from them both physically and by their lack of comprehension of the dreams. This composition suggests that Joseph, although a foreigner and former prisoner (39:20), is already well on the way to becoming Pharaoh’s closest advisor and second-in-command (41:33–41). The result of his appointment to that position is revealed in the two miniatures on the bottom register: it will ultimately bring about his reconciliation with his brothers and enable him to provide food for the Hebrews as well as the Egyptians during the coming famine.

The Golden Haggadah demonstrates the close interaction between Jewish, Christian, and Muslim culture in this period (Epstein 2011: 3; Kogman-Appel 2004). Each scene is framed with the geometric patterns typical of Islamic decoration, for example, and the figures are drawn with the long flowing bodies characteristic of contemporary Christian illuminated Bibles and Gothic art generally.

Such interweaving of influences is particularly appropriate for a narrative about the mutually beneficial engagement of Egyptians and Hebrews.

References

Brewer, Douglas J., Donald Redford, and Susan Redford. 1994. Domestic Plants and Animals: The Egyptian Origins (Warminster: Aris & Phillips)

Epstein, Marc Michael. 2011. The Medieval Haggadah: Art, Narrative, and Religious Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2004. Jewish Book Art Between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain (Leiden: Brill)

Narkiss, Bezalel. 1970. The Golden Haggadah: A Fourteenth-century Illuminated Hebrew Manuscript in the British Museum (London: British Museum)

Peter von Cornelius :

Joseph interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams, 1816 , Watercolour and gouache over pencil on brownish card

Hilaire Pader :

The Triumph of Joseph, 1657 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

Scenes from the life of Joseph, from the Golden Haggadah (upper right: Pharaoh's dream; upper left: Joseph interpreting Pharaoh's dream; lower right: the arrest of Simeon; lower left: Joseph revealing himself to his brothers), c.1320–30 , Illuminated manuscript

‘Fruitful in the Land of my Affliction’

Comparative commentary by Susan Docherty

The story of Joseph (Genesis 37; 39–45) is ‘…the most intricately constructed … of all the patriarchal histories … for sustained dramatic effect … unsurpassed in the whole Pentateuch’ (Speiser 1964: 292). Genesis 41 is widely regarded as the very centre of this dramatic tale (Westermann 1986: 85). It tells of Joseph’s unlikely rise to power in Egypt, and sets the stage for his reunion with his family after a two-decade long separation. It divides into three parts, a common pattern in Hebrew narrative: a description of Pharaoh’s dreams (Genesis 41:1–13); an account of their interpretation by Joseph (vv.14–46); and a demonstration of their eventual fulfilment, in which Joseph will play a central role (vv.47–57; Wenham 2000: 389).

These three acts are represented in turn in this exhibition. Two of the artworks reflect an appreciation of the chapter as a whole and of the interconnections between its three sections. So folio 7 of the Golden Haggadah encompasses both the dream interpretation scene and the final episode of this narrative, in which Joseph as Pharaoh’s chief advisor will welcome his family to Egypt.

In Peter von Cornelius’s portrayal of Joseph explaining Pharaoh’s dreams, too, the composition hints at the implications of this for Joseph’s future role and authority, particularly through the secondary scene at the right which shows him riding in his chariot. In the main scene Joseph alone is foregrounded, albeit with his back to the viewer, and the king and all his courtiers listen to him in respectful silence, although the sense of closeness between the two main protagonists which emerges in the Golden Haggadah is lacking.

Hilaire Pader concentrates wholly on the final scene, lavishly celebrating Joseph’s eminence as grand vizier of Egypt. The success of a Hebrew abroad was enthusiastically celebrated by both early Jews (as in Joseph and Aseneth, a romantic novel written in Greek by an unnamed author around the turn of the era), and early Christians, who saw in Joseph’s life a prefiguration of Christ’s humiliation and exaltation (as in the sermons of St Ephrem the Syrian). With rich colours and large crowds, Pader deftly conveys a sense of the size and wealth of the land over which Joseph is set, and of the splendour and power with which he is invested.

Over the course of this chapter, then, the imprisoned and forgotten slave has been transformed into a member of the Egyptian elite, second only to Pharaoh in authority and married into a high-status priestly family (vv.4–45). Ironically, it is Joseph’s apparently complete absorption into his adopted society depicted so fully by Pader that will bring about his reconnection with his Hebrew origins, when members of his family journey to Egypt during the famine (41:57–42:3).

Pharaoh’s dreams are presented in the biblical text as a true and divinely-sent message (41:25, 28, 32), reflecting a view widespread in the ancient world (Westermann 1996: 46). The providential and life-changing power of dreams is literally enacted in this narrative and in these visual representations of it, as they are instrumental in raising Joseph to greatness and ultimately enabling him to give life and prosperity to his entire clan when they migrate to Egypt (42:2; 45:18).

For the biblical narrator, however, these events are not primarily about the individual character, Joseph. Rather, they form one strand within a much larger epic about Israel’s ancestors, who encounter numerous obstacles on their way to inheriting the promises made to them by their God of land, descendants, and blessings (Genesis 12:1–3; 17:2–8; 22:16–18). Joseph’s life encapsulates the experience of these early patriarchs, and also foreshadows the key events of the exodus, when his people will become enslaved in Egypt as he was, will interact with another Pharaoh in order to gain their deliverance, and will again ultimately triumph through divine intervention (Exodus 1:1–14:31). This link between Joseph’s own life and the exodus is made explicit when he gives his second son, Ephraim, a name which recalls both the divine promises to Abraham of ‘fruitfulness’ (Genesis 12:2; 15:5; 17:2–6; 22:15–17) and the ‘afflictions’ which his descendants will suffer in Egypt (Genesis 41:52; see Exodus 3:7, 17; 4:3). It is also appropriately highlighted by the inclusion of an artistic portrayal of the Joseph narrative at the front of the Golden Haggadah, a book designed for use in the annual celebration of the Hebrews’ escape from Egypt at Passover.

References

Goodacre, Mark. 1999. ‘The Aseneth Home Page’, available The Aseneth Home Page (markgoodacre.org)

Speiser, Ephraim. 1964. Genesis: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Anchor Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Wenham, Gordon. 2000. Genesis 16–50, Word Biblical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan)

Westermann, Claus. 1986. Genesis 37–50 (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress)

———. 1996. Joseph: Studies of the Joseph Stories in Genesis (Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

Commentaries by Susan Docherty