Proverbs 31

The Wife of Noble Character

Nina Koch

Katharina von Bora, 1999, Bronze, 170 x 60 x 80 cm, Lutherhaus, Wittenberg; © Nina Koch imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

Breaking New Ground

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Katharina von Bora was the wife of Martin Luther, the sixteenth-century German Reformer. This life-size bronze statue was made by German sculptor Nina Koch in 1999 for its site outside the Lutherhaus in Wittenberg, Germany.

Koch draws on the likeness of Katharina from the famous double portrait of Luther and his wife painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1529. The smooth bronze casting of her aquiline features and upper body, contrast with the rougher textures of her dress and coat below the waist, where green oxidized patches of bronze create an impression of brocade. Katharina strides forward, giving a modern prominence to the shape of her lower body, which sixteenth-century dresses, layered with petticoats, tended to disguise more than display. Her left hand swings forward, drawing attention to the wedding ring on her index finger.

A highly competent, intelligent woman, Katharina was a pioneer in a ‘new’ kind of Christian marriage in the Western Church. Formerly a Benedictine nun, she had fled her nunnery in the early years of the Reformation, and married Luther in 1525. They lived in the Lutherhaus, which had earlier housed Augustinian monks studying at the University of Wittenberg, including the young Luther himself. The fact that, prior to the Reformation, clergy were required to be celibate (as would remain the case for Roman Catholic clergy after the Reformation) meant that there was no ready-made model of how to be a pastor’s wife. Katharina and Martin were among those who were having to negotiate this for the first time.

In this context, ‘A good wife who can find?’ (Proverbs 31:10) can be read not just as a man’s question. It became a question for a generation of women seeking how best to exemplify ‘goodness’ in their new vocations; ‘finding’—and founding—new models for how to be wives.

References

www.nina-koch.de/Stadraum [accessed 26 April 2018]

Stjerna, Kirsi Irmeli. 2009. Women and the Reformation (Malden: Blackwell), pp. 49–70

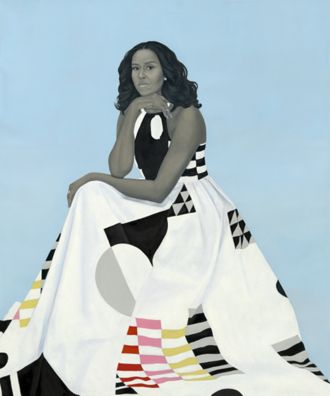

Amy Sherald

Michelle laVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018, Oil on linen, 183.2 x 152.7 cm, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; NPG.2018.15, © National Portrait Gallery

First Things

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Amy Sherald has achieved something distinctive in her painted vision of one of the most photographed women of the twenty-first century.

Michelle Obama chose the Baltimore artist for her official portrait as First Lady of USA, unveiled in 2018. It was important to Obama that her portraitist should be an African-American woman, whose family, like her own, were once slaves. Sherald deploys her signature use of greyscale for Mrs Obama’s skin, an approach that refuses to encode racial difference through the use of colour, and thus establishes what is, in the domain of portraiture, a historically-unprecedented equality between races. As Antwaun Sargent comments (2018), ‘race is central to the narrative of Mrs Obama as an “ideal” wife because she is a pioneer: a black woman who became a first lady’.

Capturing an enigmatic facial expression which is much more than just a smile for the camera, this portrait is a powerful vision of Obama’s unique character and grace, which she used to promote issues such as access to healthy food for the poor in America and education for girls worldwide. In the spirit of Proverbs 31, she spoke up for those who could not speak for themselves, and for the rights of those who are destitute (vv.8–9).

The dress worn by Obama is from the prestigious label ‘Milly’ by Michelle Smith. The wife of Proverbs 31, is also richly clothed (v.22). Sherald plays on conventions of ruler imagery by using the dress, spread in a wide triangle, to create monumentality in the composition. The bold geometric designs of black and grey on white, with red, yellow, and pink, reminded Sherald of paintings by Piet Mondrian, which she emulates by minimizing the folds of drapery. For Sherald, the dress patterns also evoked the long-standing traditions of quilting among black African-American women.

The choice of a sleeveless dress is daring within the traditions of First Lady portraits and highlights Mrs Obama’s much talked-about muscular arms. While alluding to the idea of labour in her family heritage, these are transformed in a message of contemporary beauty and physical fitness. Read together with Proverbs 31, they also speak of her arms extended towards the poor and needy (v.20), and the strength and dignity with which she clothed herself in office (v.25).

References

St Félix, Doreen. 2018. ‘The Mystery of Amy Sherald’s Portrait of Michelle Obama, 13 February 2018’, www.newyorker.com, [accessed 26 April 2018]

Sargent, Antwaun. 2018. ‘Inside the Obama Portraits Unveiling. Witnessing Visions of Black Power Shake Up a Gallery of White History, 13 February 2018’, www.wmagazine.com, [accessed 26 April 2018]

Artwork Institution Details

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg; Judith Kern and Kent Whealy; Tommie L. Pegues and Donald A. Capoccia; Clarence, DeLoise, and Brenda Gaines; Jonathan and Nancy Lee Kemper; The Stoneridge Fund of Amy and Marc Meadows; Robert E. Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker; Catherine and Michael Podell; Mark and Cindy Aron; Lyndon J. Barrois and Janine Sherman Barrois; The Honorable John and Louise Bryson; Paul and Rose Carter; Bob and Jane Clark; Lisa R. Davis; Shirley Ross Davis and Family; Alan and Lois Fern; Conrad and Constance Hipkins; Sharon and John Hoffman; Audrey M. Irmas; John Legend and Chrissy Teigen; Eileen Harris Norton; Helen Hilton Raiser; Philip and Elizabeth Ryan; Roselyne Chroman Swig; Josef Vascovitz and Lisa Goodman; Eileen Baird; Dennis and Joyce Black Family Charitable Foundation; Shelley Brazier; Aryn Drake-Lee; Andy and Teri Goodman; Randi Charno Levine and Jeffrey E. Levine; Fred M. Levin and Nancy Livingston, The Shenson Foundation; Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago; Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen; Sara and John Schram; Alyssa Taubman and Robert Rothman

Domenico Ghirlandaio

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, 1489–90, Mixed media on panel, 77 x 49 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; 158 (1935.6), © Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid / Bridgeman Images

More Precious than Jewels

Commentary by Ursula Weekes

Proverbs 31:10–31 is an acrostic, each line beginning with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Like the painting we see here, the ‘perfection’ of this highly crafted poetic form suits its purpose: the construction of a certain ideal.

In 1486, the beautiful Giovanna degli Albizzi, aged 18, married Lorenzo Tornabuoni, the son of a wealthy Florentine merchant banker. A year later, on 11 October 1487, Giovanna gave birth to a son and heir, fulfilling the ‘expected duty’ of a noble wife in Renaissance Florence, both to husband and the ruling elite of the City Republic. Within another year, however, the young Giovanna had died from complications associated with a second pregnancy. She was buried in Santa Maria Novella in October 1488.

Lorenzo was distraught and commissioned many memorials to his wife, including this portrait by Ghirlandaio, the ‘go-to’ portraitist of rich Florentine families at the time. A slip of paper attached to the wall bears an epigram by the ancient Roman poet Martial, ‘Art, if only you were able to portray character and soul, no painting on earth would be more beautiful’. Ghirlandaio accepts the neo-Platonic challenge of the epigram by making a painting that seeks to portray inner beauty through (and in addition to) outward beauty.

Giovanna’s identity as Lorenzo’s wife is prominently displayed in the embroidery of her silk brocade robe, which has ‘L’ motifs, together with other emblems of the Tornabuoni family. The profile format associates her with classical portraiture and accentuates her domed forehead, high hairline, and elongated neck. Giovanna’s moral virtue is conveyed by her upright pose and the prayer book on the shelf behind her, where we also see her virtue as a mother reflected in a string of coral beads, often used as a protective talisman for infants, and a dragon pendant that refers to St Margaret, patron saint of childbirth. This pendant, as well as the necklace worn by Giovanna, both feature large rubies that display the wealth of the Tornabuoni family, and recall the opening line of the acrostic poem in Proverbs 31:10, ‘A good wife who can find? She is far more precious than jewels’.

References

Brown, David Alan (ed.). 2001. Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra De’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Simons, Patricia. 1992. ‘Women in Frames. The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture’, in The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: Westview), pp. 38–57

Weppelmann, Stefan. 2011. ‘Some Thoughts on Likeness in Italian Early Renaissance Portraits’, in The Renaissance Portrait: From Donatello to Bellini, ed. by Keith Christiansen and Stefan Weppelmann (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 67–69

Nina Koch :

Katharina von Bora, 1999 , Bronze

Amy Sherald :

Michelle laVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018 , Oil on linen

Domenico Ghirlandaio :

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni, 1489–90 , Mixed media on panel

She Opens her Mouth with Wisdom

Comparative commentary by Ursula Weekes

Women frame the wisdom of Proverbs. The book opens with the headline theme, ‘the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom’, (1:6), learned from a father’s instruction and a mother’s teaching (1:7). Chapters 1–9 are dominated by female figures, most famously the personifications of Lady Wisdom and Lady Folly who call aloud in the streets offering divergent paths to life (Proverbs 8–9). Meanwhile, the final chapter of Proverbs begins: ‘The oracles of King Lemuel—an oracle his mother taught him...’ (31:1), providing one of the few direct references to female authorship in the Bible.

In this vein, two of the artworks chosen here are by women artists, Nina Koch and Amy Sherald. The subject of their artworks are bearers of insight and strength and exemplify the crucial role of women in social justice and cohesion—key concerns of King Lemuel’s mother (31:8–9).

Koch’s statue, with its door frame signalling the threshold between home and the outside world, reminds us of Katharina von Bora’s personal courage in crossing boundaries. We become aware of the crucial role of women in the Reformation and the social changes that Protestantism brought about for women. Katharina was a role model for a new kind of Christian wife and mother, shaping households in which the Bible and vernacular devotion were part of everyday family life.

In our own time, Michelle Obama has likewise been a pioneer, above all in becoming the first black First Lady of the United States. She spoke powerfully from this position into situations of poverty, health, education, and the need for respect for women.

Obama saw her portrait as offering a visual ideal for future generations. She said at the unveiling of her portrait:

I am thinking about all the young people—particularly girls, and girls of colour—who in years ahead will come to this place and look up and seen an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this Great American Institution ... I know the kind of impact that will have on their lives because I was one of those girls. (Pogrebin 2018)

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s portrayal of Giovanna degli Albizzi, with her pure beauty, idealizes its subject in different circumstances and to different ends. Unlike Obama, she was painted after her death, her portrait proclaiming her perfect precisely as she is also mourned as mortal. The work gives poignancy to Proverbs 31:30: ‘beauty is fleeting’. But the verse goes on: ‘a woman who fears the Lord is to be praised’, and it seems that in commissioning this work, Lorenzo genuinely wanted to ‘praise’ her for more than her outward attributes alone.

Giovanna’s large rubies recall the opening couplet of the poem, where the noble wife surpasses the value of jewels (31:10). Similarly, at the start of Proverbs, the female figure of Wisdom herself is also described as more precious than rubies (3:15) The good wife is thus directly aligned with the personification of Wisdom. Later, in the New Testament, this figure of Wisdom becomes associated with Jesus (for example in 1 Corinthians 1:30). So by a chain of association, the ideal wife can be read as directing us to God himself.

The poem closes with a focus on civic honour: ‘give her the fruit of her hands, and let her works praise her in the gates’ (31:31). Giovanna’s portrait was not only a private commemoration, it spoke a ‘civic language’, embodying the ideal virtues associated with being a wife and mother in Renaissance Florence. Michelle Obama embraced the role of First Lady of the United States with a grace and dynamism that earned her worldwide affection—‘civic praise’ on an international stage.

Katharina von Bora, by contrast, did not generally enjoy such praise in her lifetime, but often faced social isolation and poverty, especially as a widow. Yet in Koch’s bronze statue Katharina appears to stride across the centuries into twenty-first-century Wittenberg, as the modern city acknowledges one of its great historical citizens.

These works all open a further question, however: the question of whether civic honour in this world is not the real praise that counts for the ‘woman who fears the Lord’, but the praise received in that greater city, the city of Heaven. Koch’s statue can help us imagine Katharina crossing this final threshold to reach an everlasting reward.

References

Pogrebin, Robin. 2018. ‘Obama Portrait Artists Merged the Everyday and the Extraordinary, 12 February 2018’, www.nytimes.com, [accessed 26 April 2018]

Artwork Institution Details, Amy Sherald, Michelle laVaughn Robinson Obama

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Gift of Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg; Judith Kern and Kent Whealy; Tommie L. Pegues and Donald A. Capoccia; Clarence, DeLoise, and Brenda Gaines; Jonathan and Nancy Lee Kemper; The Stoneridge Fund of Amy and Marc Meadows; Robert E. Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker; Catherine and Michael Podell; Mark and Cindy Aron; Lyndon J. Barrois and Janine Sherman Barrois; The Honorable John and Louise Bryson; Paul and Rose Carter; Bob and Jane Clark; Lisa R. Davis; Shirley Ross Davis and Family; Alan and Lois Fern; Conrad and Constance Hipkins; Sharon and John Hoffman; Audrey M. Irmas; John Legend and Chrissy Teigen; Eileen Harris Norton; Helen Hilton Raiser; Philip and Elizabeth Ryan; Roselyne Chroman Swig; Josef Vascovitz and Lisa Goodman; Eileen Baird; Dennis and Joyce Black Family Charitable Foundation; Shelley Brazier; Aryn Drake-Lee; Andy and Teri Goodman; Randi Charno Levine and Jeffrey E. Levine; Fred M. Levin and Nancy Livingston, The Shenson Foundation; Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago; Arthur Lewis and Hau Nguyen; Sara and John Schram; Alyssa Taubman and Robert Rothman

Commentaries by Ursula Weekes