John 1:14–18

The Word Became Flesh

Unknown artist

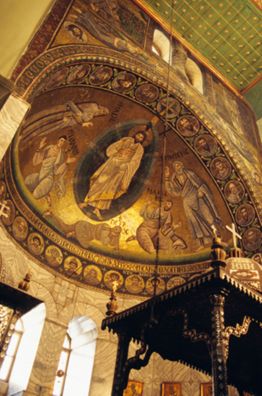

Apse mosaic of the Transfiguration, 565–66, Mosaic, Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai; LatitudeStock / Alamy Stock Photo

Transcendent Glory

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

…glory as of the only Son from the Father.

Introducing Jesus in terms of light, as the Gospel of John does, this mosaic fills the high, rounded semi-dome of the apse in the church built for Mount Sinai’s monastic community in the mid-sixth century CE by the emperor Justinian.

The materials of the mosaic illustrate Christ’s divine glory in alternating aspects of splendour, in the perpetual, repeated movement between morning and evening light. White stone, and silver embedded in glass in small cubes called tesserae, fill the apse with silvery-whiteness when morning sun lights the conch from windows above and below. In evening daylight or lamplight the whole space changes to the glow of gold, reflecting from gold-glass tesserae. Heavenly blue in almond-shaped zones of gradation surround Christ’s dazzling figure whichever background tone predominates.

This luminously dynamic intimation of Christ’s glory illustrates the Transfiguration (Matthew 17:1–9; Mark 9:2–9; Luke 9:28–36). Here, John, Peter, and James (shown and named) witness a stupendous confirmation of Jesus’s more-than-earthly identity. By an inversion typical of the writing of Sinai’s most famous abbot, John of the Ladder (John Climacus, c.579–650) the scene, instead of depicting a mountaintop, makes the height of the hollow space above the altar the mountain’s spiritual equivalent. It celebrates a pinnacle in the relationship between heaven and earth, as played out on Mount Sinai/Horeb and on Mount Tabor, where according to Anastasius, another seventh-century Sinai abbot, the Transfiguration took place.

John and James hold up their hands in a traditional gesture of prayer, while Peter, stunned, stretches out half-kneeling on the ground, holding his mantle to shield his eyes. How can they understand, in this voltaic glory, Christ’s fusion of the prophetic past with the promised future?

Still growing outside the Sinai church was believed to be the burning bush from which divinity had shone like fire. There God had spoken with Moses and given him the Law. On this same mountain, God had spoken to Elijah, sending terrifying manifestations and summoning him out of a cave. According to Luke, the revelation of Jesus shining with the glory of divinity woke his three followers out of sleep, just as the version of the scene in this mosaic seems to offer its viewers a spiritual awakening, and a promise of grace and truth in the glory of divine nature made visible in Jesus. John 1:14’s announcement here becomes dramatic experience.

Dazed by the light, John and James and Peter turn their heads to listen, hearing God’s voice explain the glory of Christ. The face of Jesus suggests his own attentive listening.

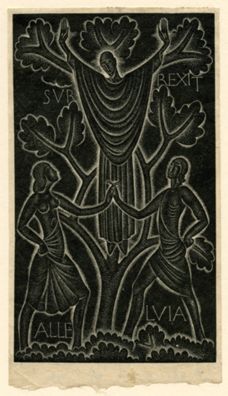

Eric Gill

Surrexit Alleluia, 1930, Wood engraving, 125 x 75 mm; Donohue Rare Book Room, Gleeson Library / Geschke Center, University of San Francisco

The Glow of Forgiveness

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

And the Word became flesh…

A glow of glory spreading like grace from the risen Jesus dominates this scene. He appears dressed in a long robe and shoes, but weightless with victory at the centre. Eve and Adam look up at him, joining their hands in an open clasp, while their other hands draw across their hips the draped garments that cover their otherwise naked bodies. His slender person is suspended as if from heaven between the adoring pair and a living tree.

Acknowledging the couple below him, Jesus inclines his head attentively in divine sympathy and love. At the same time, his dropped head and his arms now raised in blessing rather than agony mirror the familiar pose long ago given to him in representations of his death on the cross, and through that association Eric Gill makes reference to Christ’s humanity. The curving, U-shaped folds of the mantle falling from his shoulders emphasize a two-way directionality, dipping toward earth but rising with his upward gesture and spreading outward like ripples from his face.

A mystical celebration of grace and truth in forgiveness and compassion here takes on the glory of transcendence, set in a landscape of the spirit, detached from time. George Herbert Palmer, in The Glory of the Imperfect, considers the beauty of an actual tree, with ‘every leaf in order’ as a ‘finished thing’ (1898: 11–14). Here, in the two halves of Gill’s wide-spreading tree, as in the distinction between the human genders and personalities, there is a perfect asymmetry. The tree is in full leaf. Salvation is accomplished.

By placing Adam and Eve in front of the tree where Jesus hovers, Gill merges the interpretations of Old and New Testament stories: humanity’s fall from God’s grace and Christ’s self-sacrificing remedy for that fall and for humanity’s resulting troubles. In this design for Easter, Gill expresses the idea that the death of Jesus on the wooden ‘tree’ of the cross transformed the fatal tree of knowledge, whose fruit caused the couple’s expulsion from the earthly paradise of Eden, into an agent of salvation. Now they see Jesus on a tree of life, restoring their faith and hope that they will be reconciled with a loving God in a heavenly paradise.

References

Palmer, George Herbert. 1898. The Glory of the Imperfect (Crowell)

Albrecht Dürer

Christ in Emmaus, from The Small Passion, c.1510, Woodcut, 127 x 98 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Junius Spencer Morgan, 1919, 19.73.202, www.metmuseum.org

On the Peak of Perception

Commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

We have beheld his glory…

The Gospel of John’s opening chapter connects the earthly Jesus with his heavenly identity, without naming all of the revelatory events the other Gospels describe. Though a prologue, it is a place where the Resurrection, like the Transfiguration, is already being made manifest.

One of these events—seeming to echo through John’s Prologue even though not explicitly included in his Gospel—tells of Jesus’s conversation, as a stranger, with the two disciples walking to Emmaus. Responding to their dismay about his death and their bafflement about reports of his resurrection, he rebukes them:

O foolish men, and slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory? (Luke 24:25)

Wearily, they persuade him to join them for supper when they reach the town. Albrecht Dürer places them with other strangers at an ordinary travellers’ supper table set with a white cloth, in a small room.

The disciples’ clothing is eloquent: the battered outdoor hat’s wide brim is a style that had become a signature for Christian pilgrims on the road. A coat, weatherproofed with a shoulder cape and a hood, is a common enough form of dress, although the hood had for centuries been part of monastic habits that originated even before the Benedictines adopted it, as a sign of Christian humility.

A white patch of light where the tablecloth hangs in the foreground draws attention to a triangular shape: the splayed table legs below the shining head of Jesus at the apex. There is only one glass on the table, prominently placed; transparently it shows in its base a strengthening feature of handblown drinking vessels, known in glassmaker’s terms as a conical kick, a mountain-shaped bulge rising inside the glass. With these mountain shapes, Dürer hints at a parallel between this revelation of Christ’s true identity, and the Transfiguration.

In visual confirmation of his companions’ sudden understanding, when Christ breaks the bread, bright light surrounds his head, shaping a cross at the top and shining downward toward their eyes below. His gaze has already left their company, and seems to be fixed somewhere beyond time. He radiates the glory of their perception, and of his destination, before he vanishes.

References

Schaff, Philip and Henry Wace (eds). 1980. ‘John Cassian: The Twelve Books Of John Cassian on the Institutes Of The Coenobia, and the Remedies for the Eight Principal Faults, Institutes I’, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 11 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark)

Unknown artist :

Apse mosaic of the Transfiguration, 565–66 , Mosaic

Eric Gill :

Surrexit Alleluia, 1930 , Wood engraving

Albrecht Dürer :

Christ in Emmaus, from The Small Passion, c.1510 , Woodcut

Witnessing the Glory

Comparative commentary by Eunice Dauterman Maguire

…full of grace and truth…

Although no artist can, like God, make word into flesh, these scenes of glory extend and clarify themselves with lettering in the pictorial design. The words or lettering are unabashedly large and legible in all three compositions.

The Sinai mosaic names all the figures except Christ, and underlines the composition with a bordering inscription identifying the Old Testament precursors whom it depicts.

Albrecht Dürer emblazons his monogram, AD, on the end of a bench in his Emmaus scene as a sign that the print and its multiples were his creation.

Eric Gill’s Christ lifts his arms above a line of inscription that, had it been a solid shape, would have been the transverse bar of a cross, but is instead the word SUR-REXIT—Latin for HE IS RISEN—as a heavenly message interrupted by his triumphant body. From the ground below, rising above the lush plants that hide the feet of Eve and Adam is the earth’s response: ALLELUIA.

Subtle reversals glorify these scenes. The positive peak inside Dürer’s suddenly sacramental drinking glass rises from a deep depression, while the concave Sinai apse de-materializes a mountain peak, and Gill’s Christ, no longer nailed to a tree of death, raises his hands in blessing.

All three scenes express the glory of Christ’s divinity offered to the human gaze through glowing or radiating light, with his figure as the central focus in a carefully balanced evocation of time and place. The central vision in the Sinai apse dissolves all sense of local space, suspending Christ, for a moment, in heaven. The barely visible ground is only a narrow band, darkening to black shadow under Peter below the all-encompassing blaze of light. For the transcendent moment in the ordinary room at Emmaus, Dürer makes the whole supper table shine under Christ like a mountain of revelation. Gill’s stylized tree has sturdily curving limbs and multi-lobed foliage hinting at the strength and endurance of English oak. It stands in undulating, leafy countryside, on a benign earthly hillock that supersedes the drama of the hill of Calvary for the couple who represent every man and woman.

In very different ways, the three scenes honour the human wish to hold on to a vision of glory by constructing a sacred space: the high, curved semi-dome at Sinai; the wide arch, as in a church sanctuary, opening into the Emmaus room; and the special enclosure shaped by the hands of Gill’s couple in front of Jesus. They join their upright, slightly cupped hands to make a miniature sanctuary of the space inside. Above this arched space, their long, extended index fingers cross in a chiasmic pose, a visual embodiment of the X or chi that is the Greek initial for Christ, and at the same time an echo of the X that is the phonetic and visual climax of the word SURREXIT, appearing under Christ’s beneficently lifted arms.

Gill’s complicated personal relationships have yet to be fully examined in relation to the evolution of his strong religious faith, but there is a deep poignancy in his depiction of this unique sanctuary of flesh created by a man and a woman reconciled and forgiven, in timeless devotion.

At Sinai, the Transfiguration comes as the crescendo of a progression of crosses where light enters or would be reflected along the East/West axis, aligned with the mosaic figure of Christ (Maguire 1990): the eight-rayed cross of beams emanating from the transfigured Christ; the identifying cross inside his halo; just above, representing him at the apex of the bordering arch of apostle portraits, a golden cross in blue circles of heaven; above that, on the face of the triumphal arch, in similar blue circles, a sacrificial lamb against the cross; and in a blue medallion darkened for visibility between the window arches, high over the rich décor of a fictive inlaid column, a cross at the very top of the east wall.

Spiritual light shines in all three works of art. Moses and his people found darkness at Sinai, where ‘the law was given through Moses’; but as John (1:17) makes clear, ‘grace and truth came through Jesus Christ’. When the three disciples on the mountain rise from their darkness of sleep, they find the brilliance of Christ’s person. Dürer, by giving his evening Christ at Emmaus a glory of radiance not mentioned in the Gospel story (Luke 24:13–35), projects the travellers’ amazement onto Christ’s risen person. Gill’s glowing outlines bring heaven to earth with emotional intensity. In all three, a radiant Jesus seems to be matching grace and truth with glory, listening to God’s voice or to human concerns with a unique understanding as he ‘dwells among us’.

References

Dürer, Albrecht, and R. T. Nichol (trans.). 1965 [full German text 1525]. Of the Just Shaping of Letters (New York: Dover Publications)

Fehl, Philipp P.1992. ‘Dürer’s Literal Presence in his Pictures: Reflections on his Signatures in the “Small woodcut Passion”,’ in Der Künstler über sich in seinem Werk, ed. by Mattias Winner (Wirnheim: VCH, Acta Humaniora), pp. 191–224

Maguire, Eunice Dauterman. 1990. ‘Light Visible and Invisible’, unpublished paper in Timothy Verdon’s extended session, Faith, Vision, and the Visual Arts, College Art Association and Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Nelson, Robert S. and Kirsten M. Collins (eds). 2006. Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum), pp. 16–19

Commentaries by Eunice Dauterman Maguire