1 Kings 8:62–66; 9:1–9; 2 Chronicles 7:4–22

Construction and Consecration of the Temple

Giovanni Battista Ricci

Building of Solomon’s Temple, 1623–27, Gilded stucco, Blessed Sacrament Chapel vault, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome; Courtesy of the Fabbrica di San Pietro in Vaticano

The New Sacrifice

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

The vault and walls of the Blessed Sacrament Chapel on the right-hand side of the nave in St Peter’s Basilica are ornamented with panels containing gilded stucco reliefs showing scenes of salvation history, from Adam and Eve to Christ. Of these, five are devoted to King Solomon, including two showing his building and dedication of the first Temple in Jerusalem.

King Solomon, in Christian tradition, is both an ancestor and a type of Christ. The Song of Songs, attributed to him, was read by commentators like Origen and Bernard of Clairvaux as an allegory for the love between Christ and his Church. Above all, Solomon’s Temple was considered a symbolic archetype of the Church; the sacrifices performed at its dedication and later within it were seen as foreshadowings of the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary and its bloodless re-presentation in the sacrament of the Eucharist.

Thus, the prominence of Solomon and the Temple in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel asks to be interpreted in light of the chapel’s dedication. The central panel of the vault represents a chalice and host, the sacrament that is present in the active celebration of the Eucharist at the altar, and reserved in the grandiose tabernacle designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the unmistakable shape of a Temple.

The foreground of the panel shows the building of the Temple and portrays King Solomon with the artisan Hiram (1 Kings 7:13–14). Solomon is dressed in Roman-style armour, with a turban surmounted by crown. Carrying a sceptre in one hand, he points with the other to the design, while an architect hovers nearby carrying measuring calipers. In the background we see building underway: workers chisel rock, carry stones, set bricks. The pillars of the Temple are modelled on Bernini’s pillars for the ciborium surmounting the high altar in St Peter’s.

The complementary panel in the series (not shown here) shows Solomon’s dedicatory sacrifice: flames with animals burning in them and bowls for blood. In the foreground, a man with a knife holds onto a goat intended for slaughter. As Solomon’s Temple in these reliefs evokes the Church, so the bloody sacrifices once performed in the Temple are contrasted with the unbloody sacrifice of the Eucharist that takes place in the chapel, and these in turn sacramentalize Christ’s ministry in the heavenly sanctuary (Hebrews 8:2).

References

‘The Blessed Sacrament Chapel-Detail Maps’, http://stpetersbasilica.info/Altars/BlSacrament/BlSacramentDtl.htm [accessed 5 October 2020]

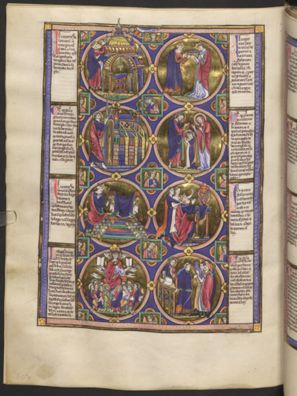

Unknown artist

'Solomon dedicates the temple; Christ thanks the Father for the Church', from a Bible Moralisée, Early thirteenth century, Manuscript illumination, 344 x 260 mm, Österreichische Nationalbibliotek, Vienna; Codex Vindobonensis 2554, fol. 50, Courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Temple and Church

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

Codex Vindobonensis 2554 is one of the earliest examples of a Bible Moralisée, or ‘moralized’ Bible—a genre of manuscript developed in the thirteenth century for the French royal family. In contrast to earlier manuscripts of the Scriptures in which text dominated, the Bible Moralisée was essentially a picture book to which short explanatory commentaries were added.

Here we see the illuminations arranged in pairs: a biblical scene, and beneath it a second visual image that suggests its ‘spiritual sense’. The accompanying text of the Bible Moralisée (seen here in the left margin) helps readers to interpret how the juxtaposed pictures can instruct them. In a way appropriate to their royal users, the scenes chosen for commentary frequently emphasize proper rule and the importance of purifying the Church.

In the first of this pair of illuminations accompanying the book of Kings, we see the full-length figure of the crowned Solomon with hands raised in a gesture of prayerful fealty, next to a schematized imagining of the interior of the Temple, represented as a ciborium with a dome. In the upper right corner of the image God (in the form of Christ, with a cross in his halo) extends his hand in blessing. The marginal text reads: ‘Here Solomon comes and gives thanks to God and praises the Lord God when he has finished the Temple, and God descends and gives his blessing to the Temple’.

Below this scene, in a second roundel, we see the image designed to accompany it: Christ standing next to a highly stylized Gothic church, with steeples and flying buttresses. Christ makes a gesture similar to Solomon’s. He wears a blue inner garment, and red outer robe—a reversal of the colours of Solomon’s clothing. They mirror each other as prefiguring type and prefigured antitype. God once again appears in the upper right, blessing. The text explains the spiritual meaning of this moment: ‘That Solomon gave thanks to God when he had finished the temple and God gave him His blessing signifies Jesus Christ who gave thanks to the Father of Heaven for finishing the Holy Church and the Father of Heaven descended and gave [His] blessing and his grace’.

As Solomon is presented as a prefiguration of Christ, so the physical Temple he built is presented as a type for the spiritual reality of the Church instituted by the Saviour.

References

Guest, Gerald B. 1995. Bible Moralisée. Codex Vindobonensis 2554, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliotek (London: Harvey Miller Publishers)

Lowden, John. 2005. ‘The “Bible Moralisée” in the Fifteenth Century and the Challenge of the “Bible Historiale”’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 68: 73–136

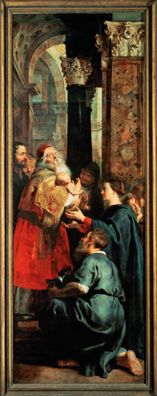

Peter Paul Rubens

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple; Right wing of triptych altarpiece of the Deposition, 1614, Oil on panel, Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp, The Netherlands; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Coming for to Carry Me

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

Shortly after the successful completion of his painting of the Raising of the Cross, in Antwerp’s Cathedral of Our Lady, Peter Paul Rubens was asked by the city’s Guild of Harquebusiers to create a complementary triptych altarpiece in the same cathedral. The subject was to be the descent of Christ’s body from ‘the Cross that carried the Lamb of the World’. Rubens, by his own account, expanded the theme to include the patron of the Guild, St Christopher, who in legend had also carried Christ, as well as other ‘carriers’ of the Saviour.

The central scene of the triptych is the Descent from the Cross. When the hinged shutters or 'wings' are open they show the Visitation and the Presentation in the Temple. When they are closed they show St Christopher on one wing and his hermit mentor on the other.

The ‘carriers’ of Christ thus include the cross itself; those who removed his body from it; Mary his mother, bearing him in the womb at the Visitation; the sage Simeon, at the Presentation; and St Christopher, whose name means ‘Christ-bearer’.

In the Presentation scene, Mary has just presented the child to the aged Simeon. Her arms are still raised in the gesture of offering. Their position forms a counterpart to her raised arms in the central panel. (Though uniquely entrusted with the carrying of Christ, Mary must let him go at the end of his life as well as at the beginning—as Simeon foretold.)

Simeon holds the baby in his arms and raises his eyes to heaven. His robes are meant to evoke those of a Jewish priest, but they could equally be those of a bishop, and he wears on his head a camauro, a fur-trimmed red hat that by Rubens’s day was worn only by the Pope.

Joseph kneels at the feet of Simeon, carrying the two birds that would be sacrificed as a vicarious offering for Jesus as a first-born son (Leviticus 12:8; 5:11). The allusion to Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross, which replaces the Temple sacrifice, is apparent.

This privileged circle of Christ-carriers is not a closed one. By implication, it extends to all Christians, who bear Christ in their hearts (Ephesians 3:17; Romans 8:10) and who—foreshadowed by Solomon’s prototype—are now the living Temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 3:16).

References

Viladesau, Richard. 2014. The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era (New York: Oxford University Press)

Giovanni Battista Ricci :

Building of Solomon’s Temple, 1623–27 , Gilded stucco

Unknown artist :

'Solomon dedicates the temple; Christ thanks the Father for the Church', from a Bible Moralisée, Early thirteenth century , Manuscript illumination

Peter Paul Rubens :

The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple; Right wing of triptych altarpiece of the Deposition, 1614 , Oil on panel

Transcendence and Sacred Space

Comparative commentary by Richard Viladesau

What makes a place sacred?

Some ancient traditions have thought of God as present in some places and not others. Frequently these are places where nature inspires awe and sublimity: mountains, for example. (Many scholars speculate that YHWH, the God of Israel, was originally imagined as a mountain/storm god, e.g. Green 2003).

But if, as in Christianity, it is thought that there can be nothing ‘outside’ God—for then God would be finite, a being among other beings—then it makes no sense to say God is here-and-not-there. Rather than God being more present in one place than another, it is we who become more present to God by particular participations in God’s limitless presence—participations that are sacramental and aesthetic.

The rabbis spoke of the Shekhinah—a word derived from the verb ‘to dwell’—to designate the luminous cloud that signified God’s presence during the Exodus migration. In the narrative in the books of Chronicles and Kings the dedication of the Temple culminates in a supernatural consumption of the sacrifice and the dramatic descent of ‘the presence’ into the inmost sanctuary, as though God replies to the invitation to ‘inhabit’ this place (2 Chronicles 7:1; 1 Kings 8:10). Prior to this, the sanctuary at Shiloh, which housed the Ark of the Covenant, was referred to as the Lord’s ‘temple’ or ‘palace’ (1 Samuel 1:9), and the Ark itself was considered the footstool of God’s ‘throne’. All this was seen as fulfilment of God’s promise to his people, ‘dwell among them’ (Exodus 25:8 NRSV).

The biblical accounts not only narrate a visible descent of God’s presence into the completed Temple, but also indicate a sacredness in the process of construction: ‘In building the temple, only blocks dressed at the quarry were used, and no hammer, chisel or any other iron tool was heard at the temple site while it was being built’ (1 Kings 6:7; cf. Exodus 20:25).

Later rabbinic stories expand this into the idea of supernatural forces at work: Solomon was assisted by demons and angels, and the huge foundation stones were hewn by the magical shamir, a substance that cut rocks by its touch (or according to some, a living creature whose mere gaze split the hardest substances (Gittin 68a-b). According to the Talmud, the enormous blocks set themselves in place unaided (Shemot Rabbah 52:4; Midrash Shir hash-Shirim 1:1:90).

The three works of art in this exhibition show how Christians over many centuries have used images of Solomon’s Temple to develop their own concepts of how God is present in our midst.

By contrast with the rabbis’ stories of supernatural aid, Giovanni Battista Ricci’s reliefs portray men doing realistically heavy construction work at the Temple site, and the dedicatory sacrifice (not shown in this panel) shows no sign of divine intervention. By their location in the Blessed Sacrament chapel of St Peter’s, the reliefs not only point to a new kind of sacred place—the Christian Church instead of the Temple—but also indicate a different conception of divine presence: a sacramental presence by the memorial meal of the Eucharist, a symbol of God’s being found in the communion of faith and love. The ‘sacrifice’ of the Eucharist is the memorial of Christ’s self-giving to God in service of the coming Kingdom.

The illuminations from the Bible Moralisée are an earlier example of this Christian shift in thinking: from the Temple as a physical building to the Temple as the spiritual reality of the Church. God is present in the communion of the faithful. The building is the house of the Church, not of God. Christians may continue to ‘constitute’ sacred spaces and times by dedicating places and events to increased awareness of God’s presence, but as the twentieth-century theologian Teilhard de Chardin said, for those who can see, all is sacred; nothing is profane (1958: 59).

Similarly, Peter Paul Rubens evokes several dimensions of the spiritualization of sacred space and action in Christian terms. In the wing of the altarpiece showing the infant Christ’s Presentation, the physical Temple now resembles a Christian church— indeed, it shows marked similarities to St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. But the real Temple is spiritual: it is Christ’s humanity (John 2:19, 21); it is the assembly of believers (1 Corinthians 3:16–17; Ephesians 2:21); it is the perfect sanctuary in heaven, where the perfect sacrifice takes place (Hebrews 8:1–2; 9:24). That sacrifice, Christians believe, no longer consists in repeated external offerings, but in Christ’s obedient self-giving, symbolized by his blood shed on the cross (Romans 5:19; Philippians 2:8; Hebrews 9:11–14; 10:5–10)—a bloodshed prefigured at his circumcision.

References

De Chardin, Pierre Teilhard. 1958. Le Milieu Divin (Paris: Éditions du Seuil)

Fine, Steven. 1996. ‘From Meeting House to Sacred Realm: Holiness and the Ancient Synagogue’, in Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World, ed. by Steven Fine (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 39–65

Goldhill, Simon. 2005. The Temple of Jerusalem (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Green, Alberto R. W. 2003. The Storm-god in the Ancient Near East (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press)

Viladesau, Richard. 2014. The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts—The Baroque Era (New York: Oxford University Press)

Commentaries by Richard Viladesau