1 Kings 10:1–13; 2 Chronicles 9:1–12

The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba

Jacopo Tintoretto

The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon, c.1545-46, Oil on canvas, Museum & Gallery at Bob Jones University, South Carolina; Courtesy of the Museum & Gallery at Bob Jones University

The Stage Is Set

Commentary by Caroline Shaw

Jacopo Tintoretto allows the hand gestures in his painting to tell the unspoken story of this encounter between the two great monarchs. Centre stage stands the richly-dressed figure of the Queen of Sheba. She inclines her head and places her right hand across her breast in a gesture of respect. Her left hand is held over her private parts in a gesture of modesty, directly alluding to the pose of antique Venus Pudica statues.

The Queen is majestic and dignified, yet respectful and perhaps slightly wary. The dark red carpet, cascading down the steps, draws our eye towards Solomon. He dominates the space between them, seated as he is above the Queen on a canopied throne between two elaborate gilded bronze pillars that allude to the pillars of the Temple named and described in 1 Kings 7:15–22.

Solomon leans forward, his open hand of welcome seeming to contradict the gesture of the bearded courtier on his right. The Queen inclines her head as she meets Solomon’s gaze across the chequered expanse of marble floor. She has come to test him with hard questions, but first she must acknowledge him as a great king.

They are not alone in their encounter. Solomon is flanked by an array of courtiers and advisers, and the Queen is surrounded by her ‘very great retinue’ (1 Kings 10:2; 2 Chronicles 9:1) of women in rich silks and velvets. Scattered in the foreground are the Queen’s gifts—golden vessels full of spices and perfumes from Saba, which call to mind the gifts of the Magi brought to honour the Christ-child.

Tintoretto seems to be showing us the preliminary greeting between Solomon and the Queen—the courtly, theatrical formalities played out in the presence of others. The court itself looks almost like a stage-set: indeed, we know that in his early career Tintoretto worked with theatre companies in Venice.

We cannot imagine, however, that the Queen would tell King Solomon ‘all that was on her mind’ (1 Kings 10:2; 2 Chronicles 9:1) in this very public setting. Soon, we might find ourselves hoping, they will retire to a more private place, perhaps to a room in the apricot-coloured building on the left, where the Queen will be free to test the King with her questions—and where the real meeting of minds will take place.

References

Krischel, Roland et al. 2018. Tintoret. Naissance d'un genie (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux)

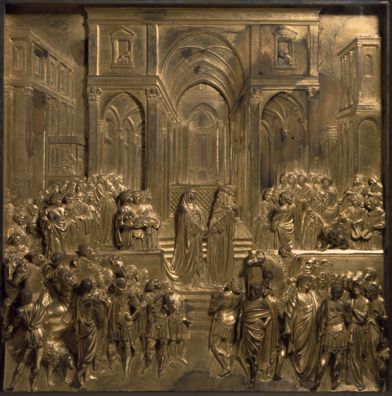

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, from Gates of Paradise, 1425–52, Gilded bronze, 79 x 79 cm, The Baptistery, Florence; Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Match Made in Heaven

Commentary by Caroline Shaw

This is the final panel of the gilded bronze reliefs which make up the doors known as the ‘Gates of Paradise’ of the Florence Baptistery, the great masterwork which Lorenzo Ghiberti spent almost twenty years of his life creating. Here, all is golden, harmonious, splendid, and eternal—is this earth, or is it a vision of heaven?

The Queen and King stand in front of Solomon’s great Temple of Jerusalem, the dwelling-place of God on earth, described in great detail in 1 Kings 5–8. Ghiberti’s Temple has followed the biblical descriptions in its general plan, although its classical pillars and gothic arches seem to owe rather more to the cathedral of Florence than to the ancient structure in Jerusalem.

In the centre of the composition, below the great porch, stand Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. They turn towards each other holding hands, in a pose which looks very like that of a marriage. This is undoubtedly a meeting of minds rather than a moment of submission: they have emerged from long private discussions to present themselves before the assembly as allies and equals.

To the right stand bearded wise men, while percussionists beat on drums and cymbals, and musicians play a melody on the shawm. Behind the Queen of Sheba stand three female attendants, carrying her long train and bearing vessels filled with spices, while all around, figures jostle to catch a glimpse of the royal pair.

It has long been suggested that this panel was intended as a commemoration of the impending Council of the Eastern and Western Churches, which opened in Florence in 1439. The Queen, as representative of the Eastern Church, and King Solomon as the Western Church, stand together in a glorious union, blessed by God.

Ultimately the attempt to heal the Great Schism was a failure. The same, however, cannot be said for Solomon and the Queen of Sheba’s meeting—nor, indeed, for Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, with their sophisticated elegance, mathematical perspective, and humanist-inspired classicism.

References

Gombrich, E.H. 1985. ‘The Renaissance Conception of Artistic Progress and its Consequences’ in Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance I (London: Phaidon), pp. 1–11

Radke, G.M. (ed.). 2007. The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Renaissance Masterpiece (New Haven: Yale University Press)

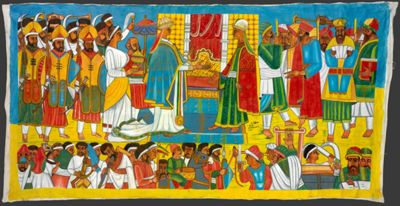

Qes Adamu Tesfaw

Scene of the meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, surrounded by their respective attendants, c.2003, Oil on canvas, 156 x 298 cm, The British Museum, London; 2012,2023.1, © Qes Adamu Tesfaw; Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

A Royal Handshake

Commentary by Caroline Shaw

The sound of music fills the air. Trumpets and drums thunder. The krar (Ethiopian lyre), and the washint (flute) pick out a melody. Swords rattle in their hilts, horses neigh, and courtiers talk excitedly as two great monarchs approach each other, extending their hands in greeting and friendship.

The setting is King Solomon’s throne room in Jerusalem. The Queen of Sheba, known as Makeda in the Ethiopian tradition, is magnificent with her domed crown, blue cloak, and a sash in the green, yellow, and red of the modern Ethiopian flag. The fourteenth-century chronicle of the Kebra Nagast or ‘Glory of Kings’, which forms a repository of Ethiopian national and religious history, traces the descent of all Ethiopian kings from this historic meeting of Queen Makeda of Saba (i.e. Sheba) and King Solomon of Israel. The artist, a former qes or priest of the Ethiopian Church, draws on the traditional iconographic elements of the Gondarine style of Ethiopian religious painting that developed from the seventeenth century, with its flat, relief-like composition, and rich red, blue, and yellow colour palette.

At first, the account of the meeting in the Kebra Nagast is very similar to that in the Old Testament: Makeda journeys to Jerusalem in order to witness the wisdom and magnificence of King Solomon. In a composition that could equally reflect the biblical text and the fourteenth-century chronicle, the monarchs stand facing each other, looking confidently into each other’s eyes. There is no hint of restraint or coyness in the Queen’s demeanour. She brings with her a similar number of attendants as those surrounding Solomon. There is an atmosphere of triumph and celebration here, but also of power made manifest: the swordsmen and spear-carriers on the Queen’s side are poised for action, and in the crowd below, drumsticks mingle with daggers.

But as the drama of the Kebra Nagast unfolds, there is a departure from the biblical text. Queen Makeda converts to Judaism and conceives a son by Solomon. Their son, King Menelik, ‘the Great King’, was the ancestor of all Amharic kings, and according to the Kebra Nagast, his transferral of the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem to Aksum brought the very abode of God to a new resting-place, in Ethiopia.

References

Budge, E. A. Wallis (trans.). 2004. The Kebra Nagast (Cosmio Classics: New York)

Chojnacki, Stanislaw. 1964. ‘A Short Introduction to Ethiopian Traditional Painting’, Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 2.2: 1–11

Jacopo Tintoretto :

The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to Solomon, c.1545-46 , Oil on canvas

Lorenzo Ghiberti :

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, from Gates of Paradise, 1425–52 , Gilded bronze

Qes Adamu Tesfaw :

Scene of the meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, surrounded by their respective attendants, c.2003 , Oil on canvas

Echoes through Time

Comparative commentary by Caroline Shaw

All three of the artworks in this exhibition convey the essential elements of the meeting between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, but the individual artists have both suggested and elaborated upon those details that they consider most important.

Qes Adamu Tesfaw, drawing on centuries of Ethiopian tradition, has emphasized the importance of the Queen. She is slightly taller than Solomon, and appears rather larger than him too, thanks to her impressive blue cloak. Her outstretched hand dominates the centre point of the composition: it is she who takes the initiative in the moment of greeting. According to the fourteenth-century sacred history the Kebra Nagast, the great King Menelik—he who would one day transport the Ark of the Covenant to Aksum—was the result of the union between Solomon and Makeda. Being descended from Solomon, and thus from King David, he is regarded by Ethiopian Christians as a direct relation of Christ himself. In this encounter, therefore, Ethiopian Christians find proof that they are the lawful successors to the Israelites as the chosen people of God.

For Lorenzo Ghiberti, the meeting of Solomon and the Queen seems to have had a different importance. In his relief panel, the two royal figures are united in a way that seems not only celebratory and jubilant, but almost sacramental. If this was indeed a direct allusion to the Council of Florence (1439–45), the image of this royal pair has a significance for Christians far surpassing a single historical moment. Church Fathers and later theologians have long agreed that Solomon is an Old Testament type, or prefiguration, of Jesus Christ. While Solomon raised the Temple of God in Jerusalem, Christ raised the House of God in the Heavenly Jerusalem. The Temple of Solomon is thus an earthly foretaste of Paradise, an idea that Ghiberti has evoked with great skill. In the Old Testament (e.g. Isaiah 60:6; Psalm 72:10), the Queen of Sheba was held up as a sign of the acknowledgement and worship of God by pagans and gentiles. The Church Fathers drew on this idea to affirm that the meeting of Solomon and the Queen represented the union of Jesus and his Church, whose members come from all corners of the world.

For Jacopo Tintoretto, who seems to have been fascinated by this story (we have at least seven surviving versions painted by him), the emphasis is more on the courtly greeting between the Queen of Sheba and Solomon, and her respectful homage to him. The king is seated high above her on an elaborate and imposing throne. It is he who decides whether she should kneel or advance towards him. Tintoretto is therefore not alluding to their blessed union, but to the might of Solomon. This has its clear roots in the New Testament, where Jesus cites the Queen of Sheba as a prophetic witness: she ‘came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon, and behold, something greater than Solomon is here’ (Matthew 12:42). This passage developed into the long-accepted idea that the visit of the Queen of Sheba was a prefiguration of the journey of the wise men or Magi, who came to adore the Christ-child. Tintoretto paints the golden vessels, the jars of perfume and tusks of ivory that the Queen brought with her, and we even catch a glimpse of a camel, framed by the arch in the background, details which call to mind images of the Adoration of the Magi.

This brief story, which occupies just twelve biblical verses, has given rise to centuries of interpretations and embellishments—scholarly, literary, and artistic. It has also inspired archaeological research. During the past fifty years, archaeologists working in eastern Yemen have found evidence of a sophisticated civilization in Ma’rib, formerly known as Saba, whose considerable wealth was founded upon the trade in frankincense and myrrh. King Solomon, for his part, actively encouraged friendly relations and trading partnerships with neighbouring kingdoms. It is possible that the meeting between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba was nothing more than an elaborate trade mission—but if so, it is one that has left a very strong echo indeed.

References

Pritchard, James B. (ed.). 1974. Solomon and Sheba (Phaidon: London)

Commentaries by Caroline Shaw