Matthew 5:1–12; Luke 6:20–26

The Blessed

Master of Papeleu

Virtue Garden, from La Somme le Roi (and Le Miroir de l'âme) by Laurent of Orleans, 1295, Illumination on vellum, 194 x 133 mm, Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris; MS 870, fol. 61v, http://mazarinum.bibliotheque-mazarine.fr/idurl/1/3053

Cultivating Virtue

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

In 1279, the Dominican Frère Laurent wrote (or perhaps compiled) the Somme le roi, a moral treatise on the vices and virtues, for King Philippe III of France. At least 15 copies of the treatise included a variation of this illumination, the Virtue Garden, including this copy from 1295 (Kosmer 1978: 303).

The seven virtues depicted in the garden are the virtues associated with the Beatitudes. But why seven, when there are eight Beatitudes? The Somme follows a tradition laid down in the early fifth century by Saint Augustine of Hippo, who counted them as seven, rather than eight, treating the eighth Beatitude as a recapitulation of the first, since both name the same reward (‘theirs is the kingdom of heaven’). Augustine also, innovatively, paired the seven Beatitudes with the seven petitions of the Lord’s Prayer and the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit as found in Isaiah 11. The symbolism of the Virtue Garden springs from these sets of sevens.

Seven trees in the garden represent the seven Beatitudes and their associated virtues—for example, ‘those who mourn’ corresponds to the virtue of patience (Kosmer 1978: 304). An eighth tree in the garden is taller than the rest; its leafy crown breaks through the top frame. The text below the Virtue Garden explains that this one represents Christ, ‘under whom the virtues grow’.

The seven women represent the seven petitions of the Lord’s Prayer; they water the trees with streams of water representing the gifts of the Spirit. In this way, the garden depicts a petition producing a spiritual gift, which in turn ‘waters’ the virtue of each Beatitude. For example, praying ‘Deliver us from evil’ produces the gift of wisdom, which nurtures poverty of spirit (Matthew 5:3), that is, the virtue of humility. According to the Somme, the seven trees (the Beatitudes) bear the fruit of eternal life. Thus, the keeping of the Beatitudes begins in prayer and ends in the reward of eternal happiness with God. In this way, the Virtue Garden points to the necessity of God’s grace and Christ’s help in becoming meek, merciful, and pure in heart.

References

Kosmer, Ellen. 1978. ‘Gardens of Virtue in the Middle Ages’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 41: 302–7

Hubert van Eyck and Jan van Eyck

The Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb), 1432, Oil on panel, 350 x 461 cm, St. Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent; St. Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium / © Lukas - Art in Flanders VZW / Bridgeman Images

Journeying toward the Lamb

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

The Ghent Altarpiece is a hinged altarpiece with multiple panels. When open, the five panels of the lower half display various groups approaching in order to worship the slain Lamb (a figure for Christ) in the central panel—a scene known as the Adoration of the Lamb and drawn from Revelation 7:9–17. Original inscriptions (now lost) identified the approaching groups as representatives of the eight Beatitudes (Philip 1971: 105–6).

On the left-hand side of the central panel three groups represent three Beatitudes: those who mourn are the prophets, shown kneeling in the left foreground and holding books representing their prophetic words. Immediately behind them stand those who hunger and thirst for righteousness—the Old Testament patriarchs, in bright multicoloured robes. Off in the distance, toward the top left of the panel, are the confessors (those who suffered persecution for their faith but did not die as martyrs)—these are the peacemakers.

On the right-hand side of the central panel are another three groups: the kneeling twelve apostles (plus Saints Paul and Barnabas) are the poor in spirit. Those persecuted for righteousness’ sake are the martyrs, who stand behind the apostles clothed in the vibrant red of martyrdom. Some bear the symbols of their martyrdom, like Saint Livinus, who holds his tongue in the pincers that tore it out. The pure in heart are the female martyrs and saints, who stand farther off toward the top right of the panel, opposite the confessors.

In the two left-wing panels, to the left of the Adoration of the Lamb, are two groups seated on horses and collectively representing the merciful: just judges on the far left, and next to them knights bearing banners (hinting at the ongoing Crusades). In the right-wing panels are the meek: on the outer right are the pilgrims, led by Saint Christopher (reported to be a giant), and next to them the hermits, including two women in the background (Mary Magdalene and, perhaps, Mary of Egypt).

The Ghent Altarpiece presents us with a puzzle: why are the Beatitudes depicted in a scene from Revelation 7?

Seeing God

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

The liturgy provides the key that explains why the Beatitudes appear in conjunction with the adoration of the Lamb from Revelation 7: both texts are readings for All Saints’ Day. The groups chosen to personify the Beatitudes likewise have their origin in the liturgy, in an antiphon (a sung response) that was sometimes linked to the reading of the Beatitudes on that same day.

The antiphon spells out particular sets of saints to be remembered: patriarchs and prophets (who are also paired together in The Ghent Altarpiece), doctors of the law (who correspond to the van Eyck’s just judges), apostles, Christian martyrs, confessors, virgins of the Lord, and anchorites (hermits) (James 2001: 128).

The Ghent Altarpiece portrays the Beatitudes as the saints—who in Revelation include all the faithful who have persevered and remained loyal to Christ, and who now receive their heavenly reward. Here, the Beatitudes have faces, some of which may be unexpected to modern viewers. For example, a few pagan philosophers (respected by many Renaissance humanists as moral teachers) appear in the group of Old Testament patriarchs to the left of the Lamb: the man in white with a laurel wreath is likely to be Virgil (Philip 1971: 106). Most counterintuitive of all is the association of crusading knights with the merciful. Medieval theology sometimes associated God’s mercy with God’s gracious offer of salvation to the Gentiles (1 Peter 2:10), and by extension, here, to the non-Christians of the Muslim East. The presence of the knights forces the modern viewer to wrestle both with this meaning of mercy (as salvation) and with the shameful intertwining of evangelism and violence in Christian history.

The altarpiece also calls our attention to the rewards of the Beatitudes: here the saints are comforted, are shown ultimate mercy on the day of judgement, and receive the kingdom of heaven. The meek and the merciful—perhaps because they have persevered in meekness and mercy—are victorious, sharing in the triumph of the Lamb over death and gathered in eschatological glory. As they approach the Lamb, The Ghent Altarpiece reveals the fulfilment especially of the promised reward for the pure in heart: ‘for they shall see God’ (Matthew 5:8).

References

James, Sara Nair. 2001. ‘Penance and Redemption: The Role of the Roman Liturgy in Luca Signorelli’s Frescoes at Orvieto’, Artibus et Historiae, 22.44: 119–147

Philip, Lotte Brand. 1971. The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Schmidt, Peter. 2001. The Ghent Altarpiece (Bruges: Ludion)

Laura James

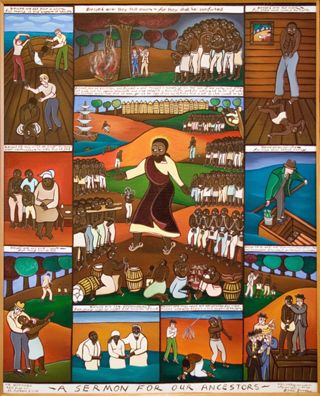

A Sermon for our Ancestors, 2006, Acrylic on canvas, 37 x 30.5 cm, Private Collection; © Laura James/Bridgeman Images, Bridgeman Images

Black is Blessed

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

Laura James, a contemporary American artist, merges the style of Ethiopian Christian art with scenes from the eighteenth-century American South, when the transatlantic slave trade sold millions of Africans into slavery in the Americas. Not surprisingly, given the cruelty of American plantation slavery, James’s work emphasizes the blessings for the persecuted (Matthew 5:10–12). The connection to Africa also renders James’s use of Ethiopic tradition particularly powerful.

In the large central canvas, a black Christ delivers a snippet from the Sermon on the Mount to groups of assembled enslaved people, many in chains. He gives them the exhortation that follows the blessing on the persecuted: ‘Rejoice and be glad…’ (Matthew 5:12) and then the famous ‘salt and light’ sayings (Matthew 5:13–14). The smaller images surrounding the central scene depict nine (rather than eight) Beatitudes. The two blessings on the persecuted, usually treated together as the eighth and final Beatitude (Matthew 5:10–11), are depicted separately in two scenes at the lower right. One shows a slave auction and the other a man lashing his enslaved fellow while being watched by the white master who commanded him to do so (in the latter, one may understand the persecuted as both the enslaved person receiving the punishment and the one forced to mete it out).

In each scene, those receiving Christ’s blessings are African men and women at various stages of their enslavement, with the exception of a white man (‘the merciful’) who conceals two enslaved people under a blanket in the bottom of his boat. Of all the individual Beatitude scenes, the largest appears just above the central section; those who mourn witness a lynching while two white men observe with folded arms.

Representing Christ as an African places him in solidarity with those enslaved. Unlike them, he is not barefoot, perhaps gesturing ever so quietly to the promise of the black spiritual that ‘All God’s Children Got Shoes’. The work’s title points both to the past (enslaved Africans) and to present-day African American viewers (‘our ancestors’). The message is clear: the suffering enslaved, and their present-day descendants who suffer still, are the blessed.

Master of Papeleu :

Virtue Garden, from La Somme le Roi (and Le Miroir de l'âme) by Laurent of Orleans, 1295 , Illumination on vellum

Hubert van Eyck and Jan van Eyck :

The Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb), 1432 , Oil on panel

Laura James :

A Sermon for our Ancestors, 2006 , Acrylic on canvas

The Concert of the Happy

Comparative commentary by Rebekah Eklund

On the one hand, it is possible to read the Beatitudes as descriptions: these are the kind of people whom God declares blessed, flourishing, or truly happy. The blessings reveal the unexpected, counter-cultural, ‘upside-down’ nature of God’s kingdom: the world declares the rich and powerful to be the blessed—but God favours the humble, the hungry, and the meek. Laura James’s A Sermon for Our Ancestors is an example of this approach. Paradoxically, those who are enslaved, raped (see the top right scene illustrating ‘Blessed are the meek’), murdered, and beaten are declared blessed.

Why? God sides with them.

On the other hand, it is possible to read the Beatitudes as implied commands, or invitations: if you want to be blessed, then be merciful. This is the interpretation suggested by the Virtue Garden illumination from the Somme le roi, in which the Beatitudes are virtues (humility, patience, kindness) nourished by the Spirit and received through the Lord’s Prayer, the prayer common to all Christians.

The Ghent Altarpiece takes a similar approach when it portrays the Beatitudes as the saints. Initially, these sterling examples of faithfulness may seem inaccessible to the layperson, holding up martyrs and apostles as exemplars to be admired rather than imitated directly. Yet Lotte Philip notes that the groups represent various levels of society, including those with higher status (the judges and knights) and those of more modest means (the hermits and pilgrims), suggesting that the Beatitudes are within reach of anyone who chooses to practise them (Philip 1971: 107). The great concert of the blessed in heaven turns out to be more capacious than we might imagine.

Each work of art takes the potentially abstract values of the Beatitudes and renders them more concrete by associating them with a specific virtue, social location, or group of people. Some connections are clear: the martyrs of The Ghent Altarpiece are obviously those persecuted for righteousness. Other identifications are more challenging, such as the association of crusading knights with the merciful. All the identifications are generative, for they prompt the viewer to explore and test the connections. Why are prophets those who mourn? Perhaps because Christian thought has closely associated mourning with penitence, and the prophets with repentance in the face of divine judgement.

Most of the Beatitudes allow for a wide range of interpretation: do peacemakers make peace between quarrelling individuals or warring nations? A Sermon for our Ancestors opts for peace between God and humanity by interpreting this Beatitude with a scene of baptism (second from left at the bottom). The Ghent Altarpiece panel implies a similar theme by linking peacemaking to the confessors, since Christians could pray to the saints to intercede with God on their behalf, thus helping to assure the forgiveness of their sins and restore peace between God and the sinner.

By contrast, the Somme draws on an earlier tradition by associating peacemaking with the virtue of temperance—in other words, the peacemakers are those who pacify their own unruly desires (see, e.g. Augustine, De Sermone Domini in Monte 1.2.9).

All three artworks place a Christ-figure in the centre: the tallest tree in the middle of the garden tended by prayer, an African Jesus with open arms delivering the Sermon on the Mount, or the slaughtered Lamb standing triumphantly on the altar of his sacrifice and surrounded by angels. This centrality suggests Christ’s role not only as the speaker of the Beatitudes but also as their embodiment and fulfilment. More than the others, The Ghent Altarpiece points to the future rewards of the Beatitudes by locating them in the heavenly throne room (or perhaps the New Creation, following Revelation 21): theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Of all the artists, only Laura James suggests the implied corollary to each Beatitude: if you are not merciful, then you will not receive mercy. If the earth and the kingdom of God belong to the meek and persecuted slaves, then what will become of the slave owners? These warnings, which are given voice in Luke’s version—‘Woe to you who laugh now, for you will mourn and weep’ (Luke 6:25b)—remain unspoken in Matthew. This confronts the contemporary viewers with our own position relative to Christ’s blessings: are we the merciful, or the merciless?

References

Philip, Lotte Brand. 1971. The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Rebekah Eklund