Matthew 15:12–14; Luke 6:39–40

The Blind Leading the Blind

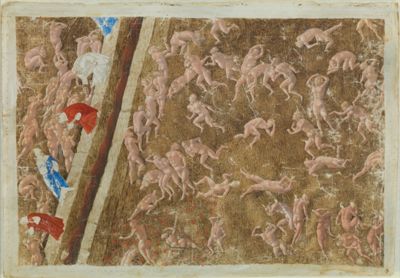

Sandro Botticelli

Inferno XV, c.1480s, Tempera and ink on parchment; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City, Reg. lat. 1896, fol. 99r., ©️ 2024 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

A Sympathetic Gaze

Commentary by Albert Godetzky

In the 1480s, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici commissioned Sandro Botticelli to illustrate Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia. Canto 15 of the epic poem introduces the Sodomites tormented in hell by burning sands. Accordingly, Botticelli’s naked figures writhe around in a fiery, undulating landscape. Their punishment recalls the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, when fire and brimstone scorched the cities and their inhabitants (Genesis 19:24–25).

Surprisingly, unlike the inhabitants of Sodom struck with blindness on account of their ‘wicked’ acts (vv.7–11), the condemned in Dante’s telling retain their eyesight: ‘each | stared steadily at us’ (Inferno 15.17–18). Inspecting Botticelli’s illustration closely, it becomes clear that the artist has depicted the Sodomites with active eyes, their pupils darting to and fro. This departure from Scripture sets up an unexpected turn in the narrative.

Dante appears three times in this scene, depicted twice in a red robe and once in a colourless outline left unfinished by Botticelli. Walking along the stony bank of the bloody Phlegethon river behind Virgil, his guide, the middle figure of Dante bends down to converse with one of the shades who has recognized him. This is Brunetto Latini, his one-time teacher who had later been exiled from Florence as a result of the factionalism between groups known as the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, a fate that was also to befall Dante himself. The two men revered one another deeply. In words that echo Luke 6:40 (‘A disciple is not above his teacher, but every one when he is fully taught will be like his teacher’), Brunetto warns Dante to stay alert and avoid those who might seek to sully his reputation through their jealousy: ‘The world has long since called them blind, a people | presumptuous, avaricious, envious’ (Inferno 15.67–68).

In offering this guidance, Brunetto reveals his remarkably clear, seer-like vision. This vision is all the more remarkable given he is amongst the Sodomites, supposedly blind to God and the laws of nature. While the social convention of his time may have swayed Dante to situate his mentor, who is believed to have been homosexual, in the fiery turmoil, Brunetto’s punishment can also been seen as the result of an unjust and ignorant power. Dante thus encourages us to reflect on our own ‘blindness’ and condemnation of those who see better than we do: we who ‘fail to see the plank in [our] own eye’ (Luke 6:42).

References

Barolini, Teodolinda. 2018. ‘Inferno 15: Follow Your Star’, Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante (New York: Columbia University Libraries). Available at https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-15/ [accessed 21 November 2023]

Schulze Altcappenberg, Hein-Th, et al. 2000. Sandro Botticelli: The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy (London: Thames & Hudson)

Pieter Bruegel I

The Blind Leading the Blind, 1568, Distemper on linen canvas, 86 x 154 cm, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; Scala/Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY

Ever Stumbling

Commentary by Albert Godetzky

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Blind leading the Blind is a highly literal representation of the parable found in Matthew 15:6 and Luke 6:39. Six men with various ocular afflictions stumble, one after another, as they follow their leader who has himself already fallen into a pit. If cause and effect in Bruegel’s composition are simple, the interpretive framework for it is, however, more varied and nuanced.

In the distance, the spire of the village church of Sint-Anna-Pede shoots up into the sky forming a crucial element in the painting’s rhythm. It occurs directly above the spot where the fragile connections established as the blind men hold onto one another’s canes (the canes they would normally use for navigation when walking separately) begin to come apart.

Multiple readings can emerge from this juxtaposition, one being that the church alone provides salvation to those who have lost their way. This interpretation would have been apt when Bruegel painted the work in 1568, at a time when Catholics were pitched against Protestants in the ongoing aftermath of the Reformation. The stumbling blind might embody a reigning lack of direction and unified leadership, the men’s tenuous link reflecting the disconnect within the Christian community.

Another interpretation coexists. Catastrophe occurs at the far right of the painting; those who follow ‘blindly’ are sooner or later bound for the same end. Life is full of traps and dangers unknown, avoided only with luck, yet ultimately ending in death. The world and time, represented by the frieze of a quotidian landscape in the background, seems an unchanging and unconcerned constant. Doctrinal differences—who is right and who is wrong—cease to matter.

The blind man, third from the right, helplessly directs his absent gaze at the church. It is with tragic futility, Bruegel seems to say, that we seek a way to pre-empt our inevitable demise. Gazing at this painting in the 1850s, Charles Baudelaire described his astonishment at such ‘blind’ faith:

I drag along also! but, more dazed than they, I say: ‘What do they seek in Heaven,

all those blind?’ ('The Blind', 1954)

References

Baudelaire, Charles. 1861. ‘Les Aveugles’, in Les fleurs du mal (Paris: Poulet-Malassis & De Broise)

______. 1954. ‘The Blind’, in The Flowers of Evil, trans. by William Aggeler (Fresno: Academy Library Guild)

Gibson, Walter S. 2006. Pieter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2017. Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

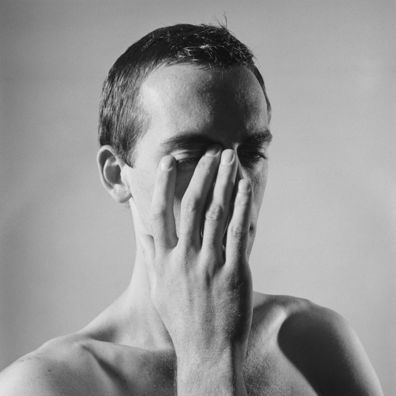

Peter Hujar

David Wojnarowicz, 1981, Gelatin silver print, 374 x 374 mm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Fellows of Photography Fund, 320.1991, ©️ 2023 Peter Hujar Archive

Blind Spots

Commentary by Albert Godetzky

In Peter Hujar’s portrait of his one-time lover, artistic mentee, and gay-rights activist, David Wojnarowicz covers his nose and mouth with his hand, emphasizing the senses that remain exposed—sight and hearing. Text and image—to be read or heard, and to be seen—were, and remain, crucial to AIDS activism, especially during the crisis of the late 1980s and 1990s. Wojnarowicz, like many other artists and activists, turned again and again in his work to pairings of text and image to convey his advocacy.

Created in the easily reproducible medium of photography, Hujar’s intimate portrait of Wojnarowicz bears an almost messianic radiance akin to a sacred icon. Closely cropped, and without references that would otherwise ground the image in a specific time and place, the photograph contains ambiguities which invite questions: is this man falling asleep or awakening? Can he see? How much?

Looking closely at the image, Wojnarowicz appears to press on one eye with his hand, perhaps removing from it some impurity. In the passage immediately following Luke 6:40, the motif of sight and blindness continues: Christ calls on his followers to remove the speck from their own eyes before removing that of others, encouraging us to recognize our own inherent prejudices before judging others (Luke 6:41–42).

Wojnarowicz urged mainstream American society to question its passivity in the face of the plight of those ‘different’ to themselves. Repeatedly in his work, he drew attention to inherent ‘blindness’, inaction, and complacency. In a photograph of 1989, which recalls the composition of Hujar’s portrait, Wojnarowicz depicted himself with his lips apparently sewn together as part of the ‘Silence=Death’ protest. To see or hear, then, but not to act—as Luke elaborates—is like building a house without foundations (Luke 6:49).

References

Smallwood, Christine. 2018. ‘The Rage and Tenderness of David Wojnarowicz’s Art, 7 September 2018’, www.nytimes.com. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/07/magazine/the-rage-and-tenderness-of-david-wojnarowiczs-art.html [accessed 21 November 2023]

Sandro Botticelli :

Inferno XV, c.1480s , Tempera and ink on parchment

Pieter Bruegel I :

The Blind Leading the Blind, 1568 , Distemper on linen canvas

Peter Hujar :

David Wojnarowicz, 1981 , Gelatin silver print

Inner Sight

Comparative commentary by Albert Godetzky

The relationship between word and image informs and deepens understanding of the three works in this exhibition.

Sandro Botticelli’s illustrated scenes from the Divina Commedia complement the text which appears in the same manuscript, inviting readers to compare written with depicted narrative. Reading Canto 15 of the Inferno, it is at first startling to encounter Sodomites capable of seeing (they are blinded in Genesis 19:11), only to have this confirmed in Botticelli’s illustration, with its suggestion of Brunetto Latini’s enlivened stare at Dante Alighieri.

In the Blind leading the Blind, Pieter Bruegel the Elder turned to the eponymous parable and offered his sixteenth-century audience a contemporary vision of the well-known biblical passage found in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Moreover, giving visual expression to the parable, Bruegel’s painting emphasizes the didactic ends of the scriptural ‘Word’ and thus ties itself into the then widening debate around the role of images in religious doctrine, and specifically the degree to which images could claim to represent truth over the written word.

The role of text equally informs Peter Hujar’s portrait of David Wojnarowicz. Here, however, the relevant text is an entire body of messages and admonitions penned by Wojnarowicz and intended to reveal the plight of a community besieged by a crisis that remained largely unacknowledged and ignored by his society.

Together, the manuscript, painting, and photograph, along with their kindred words, highlight the correlation between sight and knowledge, between visual experience and self-awareness. And, as if to accentuate the power of sight, the artists have chosen to focus, paradoxically, on the theme of blindness. In so doing, each of these three images can lead us back to the two parallel scriptural passages dealing with blindness that are the focus of this exhibition. The parable of the Blind leading the Blind was well known in Graeco-Roman thought by the time it appeared in both Gospels. Although the message is ultimately the same—ignorant leadership and false convictions lead to disaster—the two scriptural instances of the parable differ in both context and rhetoric. In Matthew 15:12–14, Jesus has just criticized the practices of the Pharisees and then addresses his disciples, telling them to disregard their fraudulent ways. His admonitions are unequivocally direct—the Pharisees are impure ‘plants… [that] will be pulled up by the roots’ (v.13). Blind to their hypocrisy, these false leaders are, according to Jesus, bound to fail.

In contrast, Luke 6:39–40, which appears within the Sermon on the Plain, is directed at a larger, more diverse audience than Jesus’s discourse with his disciples as related in Matthew 15:12–15. Here, too, the rhetoric is different. The parable of the Blind leading the Blind appears in the form of a question and, therefore, invites the listener to consider various possibilities and moments of blindness. Furthermore, in the wider context of the Sermon on the Plain, Jesus’s ministry encourages his followers to recognize the marginalized and outcast of society. Pursuing the metaphor of eyesight, Jesus asks his followers to first clear themselves of their own inherent prejudices before attempting to instruct others: ‘Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?’ (Luke 6:41).

The questions posed by Jesus in Luke 6:39–41 can be related to the three works presented here. Addressing the theme of blindness, Botticelli, Bruegel, and Hujar attempt, through their art, to initiate their viewers into a process of reflection and questioning that is grounded in the very nature of sight.

In Botticelli’s manuscript, the figure of Brunetto Latini surprises the viewer not only by being able to recognize Dante as he passes through the realm of the Sodomites, but by offering his former acolyte insight into the dangers to come.

Bruegel, in his use of detailed realism, brings the apparent irreverence of the quotidian world into sharp focus and so, too, the constant cycle of ‘blind’ faith and inevitable disaster.

Finally, Hujar’s photograph of Wojnarowicz optically documents the body of his lover as he manipulates his eyes so that, even he, an activist, may perhaps see more clearly.

Guelph or Ghibelline, Catholic or Protestant, gay or straight—examining these works of art can reveal that the social divides that we construct are relative if not entirely superficial. Whether admonishing or questioning, the rhetoric of Matthew and Luke can be seen reflected in the three works explored here; together, text and image asks us to reconsider the true depth of our vision and the nature of what we think we see and know.

References

Barolini, Teodolinda. 2018. ‘Inferno 15: Follow Your Star’, Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante (New York: Columbia University Libraries), available at https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-15/ [accessed 21 November 2023]

Gibson, Walter S. 2006. Pieter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2017. Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Schulze Altcappenberg, Hein-Th, et al. 2000. Sandro Botticelli: The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy (London: Thames & Hudson)

Smallwood, Christine. 2018. ‘The Rage and Tenderness of David Wojnarowicz’s Art, 7 September 2018’, www.nytimes.com, [accessed 21 November 2023]

Commentaries by Albert Godetzky