Matthew 8:5–13; Luke 7:1–10

The Centurion’s Servant

Stanley Spencer

The Centurion’s Servant, 1914, Oil on canvas, 114.3 x 114.3 cm, Tate; T00359, © Estate of Stanley Spencer/ Bridgeman Images; Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Away Seeking his Deliverance

Commentary by Gerard Loughlin

The Centurion’s Servant is an early work by Stanley Spencer. As so often with his paintings, the scene is set in the English village of Cookham, where Spencer lived. But this is less than usually evident, because set indoors rather than out—indeed, in the servant’s bedroom of Spencer’s own house. The boy is on the bed, and behind him, kneeling on the floor, are three figures in prayer.

Spencer had originally thought to accompany the picture with one of Christ meeting the centurion (McCarthy 1997: 68). The two separate panels would be linked by the similar positioning of soldier and servant, which is why—Spencer claimed—the latter looks as if he is walking, though lying down. But without the explanation, we might think the boy writhing—tossing and turning in a fever (as suffered by the official’s son in John 4:52). But Spencer said the picture shows the servant after his cure, when he started to move, having previously been paralysed, as in Matthew (8:6).

Though clothed, there is something Baconian about the figure on the bed, as if he were one of those mutating male bodies that Francis Bacon (1909–92) placed on beds equally as isolated and against blank backgrounds like the one Spencer depicts here. Bacon almost certainly knew the painting, having developed an early interest in Spencer, and the picture having been exhibited in London on several occasions before its acquisition by the Tate Gallery in 1960.

As with the Veronese painting and the Byzantine manuscript elsewhere in this exhibition, Spencer populates the scene with other members of the centurion’s household. But at the same time, it is also a picture of absences, of both Christ and the centurion, though the boy’s remembering of his master—now away seeking his deliverance—might be figured by the double bed on which he is lying, on the sheets of a more intimate companionship.

References

MacCarthy, Fiona. 1997. Stanley Spencer: An English Vision (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Unknown Byzantine artist

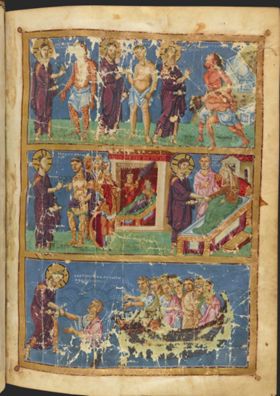

Miracles of Jesus, including healing of Centurion's servant, from Homilies of Gregory of Gregory of Nazianzus, dedicated to Basil I, 879–83, Ilumination on parchment, 435 x 300 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; MS Grec 510, fol. 170r, Bibliothèque nationale de France: ark: / 12148 / btv1b84522082

Backroom Boy

Commentary by Gerard Loughlin

This illuminated page is part of a ninth-century edition of the homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (c.329–90), a richly illustrated—and hugely expensive—manuscript gifted to the Byzantine Emperor Basil I (811–86; reigning from 867).

The page provides a visual commentary on one of Gregory’s sermons. But the book from which it comes is in a sense an ‘absent text’, since, though held in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, it hasn’t been seen—opened—since from before the Second World War. Its paint is too delicate for the further turning of its pages.

In the top register, the figure of Christ appears three times as he heals a leper, a man with dropsy, and then two demoniacs. The middle register shows Christ encountering the centurion, whose sick servant is at home, and then the healing of Simon Peter’s mother-in-law, which story follows that of the centurion in Matthew (8:14–15; see also Luke 4:38–39).

The image is like a comic-strip, to be read from left to right, with the lad at the centre of the sequence, and thus the centre of the page. He and Christ seem nearly to be in the same space because in the same register. But in fact, the lad is isolated at the back of the ‘stage’, beneath the roof of the centurion’s house and framed by its doorway. In his next appearance, Christ has moved on to Peter’s house, almost as though he has passed the boy by.

The miniaturist, working for the court in Constantinople, imagines a courtly bed for both the boy and the older woman. Indeed, the boy enjoys additional luxury, for an attendant wafts him with a fan of peacock feathers as he reclines on his couch. This might be wholly inappropriate—and therefore surprising—were he were an ordinary servant, but would be entirely fitting if (as some scholars have argued, e.g. Jennings 2003) he is thought the centurion’s beloved catamite—‘ganymede or male lover’ (Burgess 1981:7).

The theme of faith recurs in the bottom register, but now in the guise of Peter’s lack of what the centurion and presumably Peter’s mother-in-law both have. It is the story of the ‘rock’ sinking beneath the waves until rescued by Christ (Matthew 14:22–33; for the naming of the rock—Cephas/Peter—see Matthew 16:18; John 1:42), who responds with mercy, as he does to all on the page.

References

Burgess, Anthony. 1981 [1980]. Earthly Powers (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books)

Jennings Jr, Theodore W. 2003. The Man Jesus Loved: Homoerotic Narratives from the New Testament (Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press)

Paolo Veronese

Christ and the Centurion, c.1571, Oil on canvas, 192 x 297 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; P000492, Photo: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Humble Access

Commentary by Gerard Loughlin

Paolo Veronese (1528–88) probably painted Christ and the Centurion for a private domestic setting—perhaps the home of the Contarini family. Veronese shows Matthew’s version of the story (8:5–13), in which Christ meets with the centurion rather than with his envoys, as in Luke 7 (vv.3, 6).

The work proved a popular subject, with Veronese’s workshop producing another five versions. Perhaps it was so liked because Christ’s compassion for the imploring centurion is so well portrayed in the face of Christ as he turns to the entreating man, who is asking for God’s mercy, as so many others also did when their loved ones were stricken.

There is a dynamic sense of arrested movement in the picture. The centurion is dropping to his knees—his sword unbuckled and placed beneath him—as Christ, walking by, stops and turns to hear his plea.

The painting is divided into two groups. On the left, Jesus and his disciples, and on the right, the centurion with his entourage, which is itself divided between assistants and audience; between the soldiers to whom the centurion need only say ‘go’ and they go, ‘come’ and they come (Matthew 8:9), and others looking on from between the pillars.

The space between Jesus and the centurion figures the divide between their respective worlds: the evangelical and the military, heavenly and earthly. The young pageboy just behind the centurion, holding his helmet, is perhaps a reminder of the servant we don’t see, for whose cure Christ is entreated. The boy’s white cloak visually balances Christ’s tunic.

In Matthew, Jesus not only wonders at the centurion’s faith (this also occurs in Luke), but he further declares that the faith of this Gentile surpasses that of anyone in Israel, and that ‘many will come from east and west and will eat with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven’ (8:10–11). The text addresses the Gentile readers of the Gospel, who in Veronese’s painting are represented by the figures on its outer edges, by the Moor on the left, and by the soldiers on the right, wearing anything but Roman armour—knights of the sixteenth century.

As so often, the contemporary viewer is included within the biblical scene. If we too have faith in Christ, Christ will turn and hear our pleas.

Stanley Spencer :

The Centurion’s Servant, 1914 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Miracles of Jesus, including healing of Centurion's servant, from Homilies of Gregory of Gregory of Nazianzus, dedicated to Basil I, 879–83 , Ilumination on parchment

Paolo Veronese :

Christ and the Centurion, c.1571 , Oil on canvas

Absences

Comparative commentary by Gerard Loughlin

The story of Jesus and the centurion, and the centurion’s servant, is told in the Gospels of Matthew (8:5–13) and Luke (7:1–10), with a possible third version in John (4:46–53). The story begins with Jesus entering Capernaum, where—as told in Matthew—he encounters a centurion. As in other healing stories, it is the afflicted who approaches Jesus, convinced that Jesus can help; can cure his servant. But the supplicant is a centurion, a member of the occupying Roman army. He is not a fellow Jew, though a friend of Jews. He is an outsider, though one who nevertheless is prepared to reach out to a man he recognises as able to accomplish what Rome cannot deliver. The centurion has only to speak a word to have his slaves obey him, and he believes Jesus need only speak and his slave will be cured. The implied parallel suggests that such curing is a matter of commanding the spirit that harms the boy—a spirit over whom the centurion has no authority, but Jesus does.

When Jesus dies in Luke, a centurion proclaims his innocence (23:47). In Matthew, following the darkening of the sun and the quaking of the ground, a terrified centurion cries out: ‘Truly this man was God’s Son!’ (27:54; see also Mark 15:39). These soldiers echo the faith of their earlier comrade. They are in a way versions of one another: seeing what others fail to recognize, believing what others doubt.

One of the problems for an artist representing the story is that the curing of the servant happens at a distance—off-stage. Jesus never meets with the boy. Indeed, in Luke’s telling of the tale, Jesus never even meets with the centurion, who entreats via intermediaries, sending Jewish elders to Jesus. It is they who plead for the centurion: ‘He is worthy of having you do this for him, for he loves our people, and it is he who built our synagogue for us’ (7:4–5). Again, as Jesus draws close to the centurion’s home, it is friends of the centurion, not the centurion himself, who relay the message that he is not worthy to have Jesus enter his house, come under his roof.

Why is the centurion so concerned for his servant? What is this servant—this doulos (slave)—to him that he would appeal to Jesus for his saving? The answer might lie in the fact that in Matthew the centurion refers to his ‘boy’ (pais), which may not be in the sense of ‘child’ or ‘son’, as sometimes suggested, but in the sense of a youth, a lad, the younger man in a pederastic relationship. Such a relationship, of an older man with a younger, was the expected form that male same-sex relationships took in the ancient world. For a Roman citizen, like the centurion, all sexual relationships would have to be with those who were deemed socially inferior. Women fell into this category, but if the relationships were with men, then they would be with younger men—if free-born—or else with slaves. If the centurion’s pais was such for him it would explain his concern. It was his boyfriend who needed curing. And if it seems unlikely that Matthew would have Jesus respond positively to such a person and such a relationship, we should remember that it is Matthew who has Jesus tell the ‘chief priests and the elders’ (21:23) that ‘the tax collectors and the prostitutes are going into the Kingdom ahead of you’ (21:31).

The centurion’s statement that he is not worthy to have Jesus come under his roof (an unworthiness that is doubled in the Lukan version by having it relayed to Jesus by others) became the cry of every communicant Christian when it entered the liturgy of the Mass as a prayer before—in a reverse of the Gospel story—the reception of Christ in the consecrated bread; Christ entering under the roof of the mouth, into the house of the communicant’s body. ‘Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed’. Thus transferred, the centurion’s words become a statement of faith in a presence seemingly absent, of Christ in the host, and of his power to cure the spirit as once he had cured the believing soldier’s absent pais.

References

Brubaker, Leslie. 1999. Vision and Meaning in Ninth-Century Byzantium: Image as Exegesis in the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Salomon, Xavier F. 2014. Veronese (London: National Gallery)

Commentaries by Gerard Loughlin