Habakkuk 3

Brushes with Infinity

Lucas Samaras

Room No.2 (The Mirrored Room), 1966, Mirror on wood, 243.84 x 243.84 x 304.8 cm, Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1966, K1966:15, © Lucas Samaras, courtesy of Pace Gallery; © Lucas Samaras, courtesy of Pace Gallery; Photo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery / Art Resource, NY

Seeing Again

Commentary by Jane Petkovic

Lucas Samaras’s Room No.2 (1966), more often referred to as the Mirrored Room, built upon the earlier interactive art of Marcel Duchamp (Hopkins 2014). Samaras’s installation measures eight feet by ten feet; the entire space mirrored with panels, inside and out. One corner functions as a concealed door to admit ambulant viewers. Those who enter occupy a dizzying space. Reflections proliferate in an endless series, populating all six planes of the room.

This is art reconceived. No longer something to be seen, or venerated, from a distance, this is art that can literally be stepped into. Viewer becomes participant, a subject of infinite reflections. As the viewer moves, so do the reflected images, thereby challenging the notion of art as a static object. This is art overtly conscious of its ‘otherness’. It is a space set aside; an other-worldly insertion into the ordinary and the everyday. As when it was first exhibited, Room No.2 still challenges assumptions, not only about the nature of art, but about our own.

It is this sense of difference and separateness that especially connects Samaras’s installation with the experience of seers and prophets. Habakkuk’s hearing of God’s words sets him apart but so, too, does his anguished seeing (Habakkuk 1:3; 3:1–15). Habakkuk becomes a ‘place’ of acute spiritual engagement. The brutality Habakkuk witnesses is disorienting and disordering (1:14–15). Violent images multiply, shaping a future of despair. Such violence has effectively sterilized his world (3:17).

In what some may find its claustrophobic sterility, Samaras’s glass Room speaks to Habakkuk’s distress. The mirrored table and chair that are sometimes installed within Room No.2 are ambivalent presences. Their ordinary forms are rendered dysfunctional by their mirrored glass surfaces. The usual activities around a table—eating and working—need some undisturbed time. The frenetic environmental stimulus of Samaras’s room is a constant disturbance. As Habakkuk finds in the midst of his own situation of chaos, it is a struggle to hear or see beyond a current turmoil.

References

Hopkins, David. 2014. ‘Duchamp, Childhood, Work and Play: The Vernissage for First Papers of Surrealism, New York, 1942’, Tate Papers, 22, available at https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/22/duchamp-childhood-work-and-play-the-vernissage-for-first-papers-of-surrealism-new-york-1942 [accessed 24 September 2020]

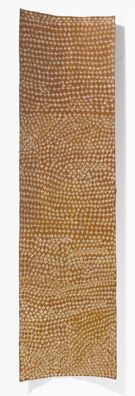

Gulumbu Yunupingu

Garak IV (The Universe) , 2004, Natural earth pigments on eucalyptus bark, The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; 2005.108, © 2019 ADAGP, Paris / ARS, New York; Photo: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra / Bridgeman Images

Seeing in the Dark

Commentary by Jane Petkovic

Australian Aboriginal artist Gulumbu Yunupingu (c.1943–2012) instantiated some of the characteristics of a prophet. Yunupingu began to paint in obedience to a command given her in a visionary experience (Eccles 2012). This prophetic painting mission began in the last decade of her life.

Garak [The Universe] IV does not depict the constellations her people revere as sacred. Instead, it shows those ordinary stars anyone may see against a dark night sky. Yunupingu only painted using natural ochres. The flattened eucalyptus bark panel of Garak IV is covered with meticulously-rendered simple crosses in white, over-painted with a finer brush in black. Influenced by her father’s paintings, a yellow dot is placed centrally in each one, suggesting astral eyes. These stars not only receive our upward gaze, but also return it. As her mother had once told her when a child, sometimes the stars shed tears over us.

White dots on the red ground infill gaps, sometimes jostling the cross-forms. These are the stars our eyes cannot see which are nevertheless present in the universe. Even those stars we can see fade from our vision at daylight. Conversely, our immediate local world vanishes in night-time dark. Different conditions reveal or conceal the same objects.

Seeing differently, so as to reveal the unseen, characterizes the vocations of both prophets and artists. Yunupingu saw in myriad stars a metaphor for myriad people (Perkins 2010: 232). Her astral sea swells and swirls rhythmically, effected by the subtly differing star sizes, densities, rotations, and angles. Her painted distillation of the universe is one where no presence is overlooked. In her hands, it becomes a patterned evocation of inter-connectedness; a vision of unity.

Habakkuk, too, finds inspiration through attending to God’s work. Although the work of divine salvation evokes dread and awe (Habakkuk 3:2–16), Habakkuk is finally calmed, able to anticipate the light of restored order, even in blinding darkness.

Stars appear to us as we prepare to sleep. In that altered state, we may dream. In this different type of seeing, we may participate in the visual readjustments of prophet and artist.

References

Eccles, Jeremy. 2012. ‘Artist Saw the Stars Crying, 13 June 2012’, www.smh.com.au, [accessed 24 September 2020]

Perkins, Hetti. 2010. Art + Soul: A Journey into the World of Aboriginal Art (Carlton, Victoria: The Miegunyah Press)

Skerritt, Henry F. (ed.). 2016. Marking the Infinite: Contemporary Women Artists from Aboriginal Australia, from the Debra and Dennis Scholl Collection (Prestel: Nevada Museum of Art and DelMonico Books)

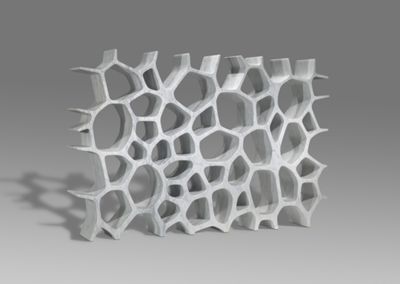

Marc Newson

Voronoi shelf , 2006, Carrara marble, The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; 2015.1717, © Marc Newson, Ltd.; Photo: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra / Bridgeman Images

Piercing Beauty

Commentary by Jane Petkovic

The Voronoi shelf of Australian industrial designer, Marc Newson, materializes a geometric concept. Voronoi diagrams are formed when a given set of points is plotted on a plane. This plane is then ‘divided into cells, each cell covering the region closest to a particular centre’ (Lynch 2017). The resultant cells form convex polygons, variable in size. Newson’s polygon cells are sinuously organic, pierced into a massive stone block. First excised using precision machinery, their smooth edges are rounded by hand-finishing.

The word ‘shelf’ immediately suggests a storage unit or piece of display furniture, which this object was designed to be. At the same time, Newson’s ‘shelf’ references the word's geological usage, as in ‘a projecting rocky ridge’—though this sculpted form visually challenges the massive solidity which that latter phrase evokes.

The Voronoi shelf constitutes itself as a lace-like pattern of negative space. The excised cells are made legible by the seamless boundaries of connecting Carrara marble. This confounds expectation of how stone is used. Carrara marble is valued for its quality, beauty, and strength, and is well-known for its historic use by sculptors. Newson’s design repeatedly punctuates and evacuates that precious material. Here is a different iteration of stonework. Stone’s aesthetic potential is expanded through the sacrifice of much of the material. Eviscerated, the multiple excisions expose an inner patterning of mineral veins.

Habakkuk 3 may be read as a spiritual-literary equivalent of the positive possibilities of negative space. Babylonian violence meant ‘the fields yield no food … and there is no herd in the stalls’ (v.17). God appears to be silent and inactive while wickedness destroys the good. God had intervened in the past to destroy oppressors but this now seems relegated to the past. The prophet, then, faces a stark choice. He can either abandon hope in a loving God, or retain faithful trust. The latter requires humility, relinquishing a desire to force God’s hand. Habakkuk makes a virtue of his negative space, able at last to ‘wait quietly’ (v.16b).

His suffering results in moral virtue. As with Newson’s delicately traced yet weighty sculpture, Habakkuk’s piercing realizes inner beauty.

References

Lynch, Peter. 2017. ‘How Voronoi Diagrams Help Us Understand Our World, 23 January 2017’, www.irishtimes.com, [accessed 7 April 2019]

Lucas Samaras :

Room No.2 (The Mirrored Room), 1966 , Mirror on wood

Gulumbu Yunupingu :

Garak IV (The Universe) , 2004 , Natural earth pigments on eucalyptus bark

Marc Newson :

Voronoi shelf , 2006 , Carrara marble

Pursuing the Incarnation

Comparative commentary by Jane Petkovic

Gulumbu Yunupingu’s Garak IV, Lucas Samaras’s Room No.2, and Marc Newson’s Voronoi shelf, use motifs of connectivity. For Yunupingu, it is stars; for Samaras, mirrors; for Newson, repeating cells. For the Prophet Habakkuk, it is the communal memory of his people.

The materials of Garak IV—natural pigments and tree bark—literally ‘earth’ the stars we see when looking up. This visual ‘upward’ trajectory follows the upward direction of animal and vegetal growth. Yunupingu’s stars signal our shared universe as something alive and watchful. Her painting is her contemplative, appreciative response. Looking up facilitated her people’s spiritual growth and creativity, and her own. In remote regions, stars appear against a black sky, yet Yunupingu paints a red ground. Our perception of a black night sky is a relativity, not an absolute. Looking up, we encounter the limit of our sight. No eye can see all the celestial bodies. If we could see the luminescence of every star in the universe, all darkness would be dispelled in a field of light.

Yunupingu’s stars are motifs that also speak of time and transcendence. Stargazers process photons emitted years earlier. This refigures our norm of understanding. We do not look upon the universe as it is, but as it was. It is not the past that eludes us, but an ungraspable present.

This schematic pattern is reversed in Samaras’s installation. Inside Room No. 2, viewers are seemingly suspended in space. Caught in a series of reflections, the multiple images regress in scale until they are lost to view, projected into infinity. Reflected viewers become a future memory of themselves, becoming like stars. The future into which they are projected, though, offers neither change nor development. In contrast to the upward growth implied in Yunupingu’s work, Samaras’s implies a developmental unravelling. Here, ‘future’ presents as an endless and sterile iteration of ‘present’. For all its shimmering surfaces, Room No.2 suggests an unsettling and ambivalent vision of connectivity.

The form of Newson’s Voronoi shelf signals a more dynamic alternative. The marble rhythmically connects the cavities. These tessellated cells could indefinitely proliferate, their number limited only by the size of the marble slab (admittedly a significant practical limitation). Newson’s shelf explicitly gestures to this theoretical inexhaustibility. His stone connections energetically reach upward and outward at the perimeters of his work. These open forms imply the boundlessness of mathematical possibility. His shelf speaks the paradox of infinity set in stone.

Yet Newson’s Voronoi shelf does not ‘set’ so much as ‘liberate’. His cells are, in one sense, not there. Obliterated stone—a nothing—becomes in Newson’s shelf the something around which his remnant stone is organized. Open space, not only the substance of the stone, becomes a focus of Newson’s sculpture. This is material put to singular, unusual use. Newson’s shelf exposes the unseen in two ways. The excisions reveal the marble’s inner striations. They also frame the invisible. The emptiness of spaces becomes organized as a perceptible pattern of interconnecting forms.

Just as Newson makes unusual use of his material, so the prophecies of Habakkuk fall outside the expected type. Scholarly opinions regarding Habakkuk 3 vary. Some hold that Habakkuk himself may be the one who had the theophany described. Others hold that Habakkuk 3 may be reproducing an earlier vision, given to someone else (Tuell 2017: 264). Either way, Habakkuk has had an extraordinary spiritual encounter with God. He has heard of tremendous events which he interprets as the work of God in human affairs (Habakkuk 3:2). He has seen their effects (v.7a). Strengthened by a belief that God is at work, Habakkuk directly petitions Him.

Habakkuk regains his confidence that God’s ‘eyes’ see the eviscerating effects of unrelieved misery. He has been reminded of how God can explosively redirect human affairs. Chapter and book culminate in a first-person proclamation of trust in God’s continuing—and sometimes, astonishing—providence. Habakkuk, whose burden was to see clearly his society’s dark ills, can finally see them differently in the light of God’s revelation. He is able, that is, to look ‘up’ and envisage a different future.

Yunupingu, Samaras, and Newson, take the uncircumscribed (the universe, infinite reflections, space) and circumscribe them as painting, installation, sculpture. Habakkuk sees in the circumscribed affairs of the world the uncircumscribed possibilities of God. In this way, these three artists and this prophet can be read as pursuing the way of the Incarnation: circumscribing infinity so that human finitude may see it, and even participate in it.

References

52 Insights. ‘Marc Newson: The Consummate Designer, 22 December 2016, www.52-insights.com, [accessed 24 September 2020]

Floyd, Michael H. 2000. Minor Prophets, Part 2, Forms of the Old Testament Literature, 22 (Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans)

Newson, Marc and Christopher Frayling. 2015. V&A Annual Design Lecture: Marc Newson in Conversation with Professor Sir Christopher Frayling, 8 June 2015’, www.youtube.com, [accessed 7 April 2019]

Perkins, Hetti (curator). 2015. Earth and Sky: John Mawurndjul and Gulumbu Yunupingu (Healesville, Victoria: Tarrawarra Museum of Art)

Scouteris, Constantine. 1984. ‘“Never as gods”: Icons and their Veneration’, Sobornost Incorporating Eastern Churches Review), 6.1: 6–18

Stubbs, Will. 2013. ‘Gulumbu Yunupingu: We Can All Look at the Stars’, Artlink, 33.2: 104–07

Commentaries by Jane Petkovic