Habakkuk 1–2

From Protest to Faith

Dion Futerman

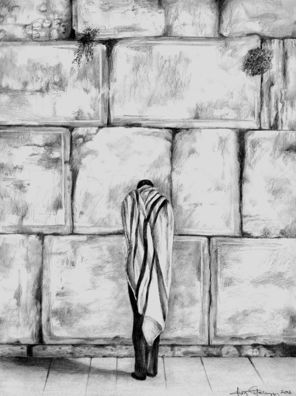

Ani Ma'amin (I Believe), 2016, Graphite pencil on paper, 210 x 300 mm, Collection of the artist (?); © Dion Futerman

‘I Believe’

Commentary by Jin H. Han

In this drawing with a pencil on paper, South African–Israeli artist Dion Futerman presents a figure in prayer who stands before a wall with his head bending low. The image does not show his face, but the hunched shoulders compel viewers to recognize the posture of a person in prayer.

The wall is undoubtedly ha-kotel ha-ma‘aravi, the Western Wall in the Old City of Jerusalem. The location powerfully summons the memory of the fall of Jerusalem commemorated on the day of Tisha b’Av, when the Jewish people reflect upon the repeated disaster in history and other colossal catastrophes that took place elsewhere.

The figure’s two feet are not planted squarely and so suggest tentativeness, perhaps even precariousness. The tallit (his prayer shawl) covers a body that may be mourning. Above him, we can observe a few plants that have managed to find their path to life through the cracks of the stone.

The Hebrew title of the artwork, Ani Ma’amin (‘I Believe’), is derived from the teaching of the famous twelfth-century rabbi Moses Maimonides, who taught the Thirteen Principles of Faith. He began each line of the faith statements with ’ani ma‘amin be-emunah shelemah (‘I believe with full faith’). Principle 12 mandates persistent waiting for the coming of the Messiah, recalling the counsel of God, who said to the prophet, ‘If it seems to tarry, wait for it; it will surely come, it will not delay / but the righteous will live by their faith’ (Habakkuk 2:3–4).

During the Holocaust, Ani Ma’amin was sung by ‘pious and obstinate Jews in the ghettos and camps’ (Wiesel 1973: 11). Set to several tunes, the lyric continues to be performed in the commemoration of victims of those horrors. Many also recite it at the end of their morning prayer.

Perhaps, the supplicant in Futerman’s drawing is also at his morning prayer. The shadow cast over him insinuates that the sun rises behind him as he prays. The hour recalls the prophet’s counsel in verse 3b (‘If it seems to tarry, wait for it; it will surely come, it will not delay’).

References

Wiesel, Elie. 1973. Ani maamin: A Song Lost and Found Again; Music for the Cantata Composed by Darius Milhaud, trans. by Marion Wiesel (New York: Random House)

Unknown French artist

Quatrefoil 19 Upper (Habakkuk), The Lord Forces the Prophet to Write of the Doom of Babylon, 13th century, Stone, Amiens Cathedral, West Facade; Photo: © Dr Stuart Whatling

‘Make It Loud and Clear’

Commentary by Jin H. Han

Quatrefoil 19 is situated under the buttress statue of Habakkuk in the west façade between the north and central porches of the High Gothic church of Amiens Cathedral. It depicts the prophet (seated) ready to receive a revelation from God, as recorded in Habakkuk 2:2. The prophet is about to write it down to make it available to those who must receive it and gain faith. They will be sustained by the prophet’s delivery of this message (2:4b).

God—depicted anthropomorphically—stands before the prophet in the quatrefoil and has a nimbus that signifies radiant divine glory. His hand is extended toward the prophet, conjuring the context of numinous communication. Seated like an ancient scribe, Habakkuk has the writing tablet on his lap, recalling a time before writing desks or tables were invented. His feet are resting on a footstool.

Christians and others of medieval and later times would have readily associated the standing divine figure with Christ. Christ is delivering his prophetic message to Habakkuk as though dictating his good news to a gospel writer. John Ruskin, the famous Victorian art critic, wrote forthrightly, ‘The prophet is writing on his tablet to Christ’s dictation’ (2008: 231).

Whereas the scene undoubtedly reproduces Habakkuk 2:2, which underscores the writing down of the vision of what God will ultimately do (2.3a), the scene captures the moment just before writing begins. We see the prophet giving full attention to the divine figure, seeking to grasp and comprehend the message before he writes it down for others. The prophet’s head is tilted, suggesting attentiveness. The relief recalls the declaration of the prophet who has just said, ‘I will keep watch to see what [the Lord] will say to me’ (2:1). At the ‘appointed time’ (2:3), God will grant the vision to the prophet who strains to hear God’s words.

References

Ruskin, John. 2008 [1881]. Our Fathers Have Told Us, Part I: The Bible of Amiens (Oxford: Benediction Classics)

Donatello

The Prophet Habakkuk (called 'Lo Zuccone'), 1423–35, Marble, h. 195 cm., Museo dell' Opera del Duomo, Florence; Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Prophet on High

Commentary by Jin H. Han

Donatello produced both this sculpture and one of Jeremiah for niches on Giotto’s fourteenth-century bell tower (campanile) adjacent to Florence Cathedral. Once installed, his work became part of a larger programme of sculptural reliefs and statues on the tower, depicting sibyls, prophets, patriarchs, and other Old Testament figures. The statue is heavily weathered, and some have suspected that it was a representation of another prophet like Elisha—known to be bald-headed (Rose 1981; see 2 Kings 2:23)—but the majority agree that it is Habakkuk.

The sculpture brings the prophet vividly to life, with his hairless pate, intensely-focused eyes, wide mouth, and parted lips (Coggins & Han 2011: 44). Writing a century after its creation, Giorgio Vasari, the painter and famous artistic biographer, praised the work’s naturalism with superlatives, declaring it ‘more beautiful than anything Donatello had ever done’ (Conaway & Bondanella 1991: 151).

Donatello liked to call it lo Zuccone (meaning ‘the pumpkin-head’ or ‘gourd-head’), probably as a term of endearment. The sculptor apparently regarded it more as a companion than as a lifeless piece of marble. He used to swear by it, saying, ‘By the faith I place in my Zuccone’ (ibid: 151–52). Vasari’s biography also states that while Donatello was working on the statue, the Florentine artist would address it with a stare, ‘Speak, speak, or be damned!’ (ibid), leaving later generations to wonder whether Donatello thought he was speaking to the prophet or to the sculpture he was creating.

Given the prophet’s denunciation of idols that could not speak (Habakkuk 2:19; recalled by Vasari), it seems all the more significant that Donatello gave his statue an open mouth. This is a prophet who spoke the words of the Lord.

It is now housed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, while a replica stands as one of the sixteen prophet figures on the Campanile of the Cathedral, looking down on the worshippers who throng the piazza below or who pass in their thousands into the cathedral. Undoubtedly, Donatello gave a thought to the angle and the perspective from which it would have been viewed, and the proportions of the figure are adjusted for the fact that it was to be seen from below and at a distance. Even from afar, the posture of the prophet communicates his passion, as he delivers his urgent prophetic message to the people of God.

I will stand at my watch-post,

and station myself on the rampart. (2:1)

References

Coggins, Richard, and Jin H. Han. 2011. Six Minor Prophets Through the Centuries (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell)

Conaway Bondanella, Julia, and Peter Bondanella (trans.). 1991. Giorgio Vasari: The Lives of the Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Rose, Patricia. 1981. ‘Bald, Baldness, and the Double Spirit: The Identity of Donatello’s Zuccone’, The Art Bulletin 63.1: 31–41

Dion Futerman :

Ani Ma'amin (I Believe), 2016 , Graphite pencil on paper

Unknown French artist :

Quatrefoil 19 Upper (Habakkuk), The Lord Forces the Prophet to Write of the Doom of Babylon, 13th century , Stone

Donatello :

The Prophet Habakkuk (called 'Lo Zuccone'), 1423–35 , Marble

‘Do Not Let Go’

Comparative commentary by Jin H. Han

Donatello’s statue of Habakkuk has the air of someone burdened with serious questions. His searching gaze reflects a person who, as we see in the opening chapters of this prophetic book, is deeply troubled by the divine silence in the face of rampant violence.

In the text, the prophet complains that he has been engaged in protest for some time. The open mouth and tensed body of Donatello’s figure can be interpreted as a recognition of this protest. However, God has been unresponsive to his cry of ḥamas! (‘violence’ in Hebrew)—a distress call that should warrant an immediate response from anyone who is within earshot (see Job 19:7). The prophet concludes that the deleterious deity refuses to offer any aid, forcing the innocent to suffer helplessly. To make it worse, God’s lack of response promotes the slackening of Torah observance, paralyzing the course of justice.

Habakkuk’s remonstration brings forth a distinctive feature of the biblical discourses of expostulation. Unlike other tragic figures in ancient and modern literature, the prophet refuses to acquiesce to the caprice of fate or to the divine whim. He demands repair, and his demand recalls many servants of God, including Abraham, who interceded for the sinners of Sodom (Genesis 18:23–33); Jeremiah, who lamented on behalf of his generation (Jeremiah 8:18–22); and Job (Job 9:15–24).

The Lord provides a preliminary answer for Habakkuk and advises him to study the scenes of the international world. God is ‘rousing the Chaldeans’ (1:5). God is going to use them as the instrument of punishment. Their military might will dispense divine judgement. The divine answer leaves the prophet baffled, however. His question in verse 12 borders on sarcasm, when he says to God, ‘Are you not of old?’. The prophet finds God’s remedy neither to reflect a grasp of history nor to provide a durable resolution to the problem at hand. The prophet points out the irony of a perpetuation of violence being built into God’s administration of justice. To punish the wicked, the prophet argues, God seems to plan to call in those who are more wicked than they are.

Habakkuk is not going to let God off the hook easily. He is not going to settle for a facile argument that attempts to justify God’s way. The prophet climbs up the watch-post with determination and eagerness to receive a word from the Lord (2:1). God answers him again (2:2). In this exchange that simulates a conversation, God and the prophet are engaged in a shared project to defeat the injustice that threatens to prevail over the world. Hope is conceived and can then be conveyed to others, thanks to the prophet’s stubborn supplication.

God asks the prophet to ‘write the vision’ (2:2). The revelation will be plain and will be available to all who seek God. It has been heard in the countless locations where worshippers have gathered ever since—including the Temple in Jerusalem, the entrance of the Cathedral of Amiens, and the campanile of Florence Cathedral, where Habakkuk’s prophecies can be equated with the calling of the bells (the locations of the three artworks in this exhibition).

According to verses 3–4, the vision given to the prophet has to do with the end, which is sure to come even if it may seem to tarry. In the intervening period, ‘the righteous [shall] live by their faith’ (v.4b; the auxiliary verb added). Through the centuries, this counsel of faith has received several interpretations. For example, it may well be construed as a double-edged divine commandment that mandates believers to have faith in God and pursue their life with faithfulness.

Based on these verses, Moses Maimonides constructed his famous Thirteen Principles of Faith, each of which begins with ’ani ma’amin, echoing verse 4b. Over the centuries, the Jewish people have sung ’ani ma’amin to a number of tunes including the one that Rabbi Azriel David Fastag composed by humming it on the way to the death camp at Treblinka. The same tradition of ’ani ma’amin inspires Dion Futerman to illustrate the mournful prayer at the Western Wall in 2016. Grief is there, but the faithful shall not let go of hope, as the nineteenth-century Rabbi Nachman of Bratzlav taught, ‘Do not despair. Do not despair. It is forbidden to despair’ ('Asur Lohayitiesh'). Even if the coming of the Messiah seems to tarry, the delay will not destroy the faith of the faithful.

Habakkuk the prophet juxtaposes the life of hope and faith with treachery, exploitation, violence, and a false sense of security in the world (2:5–13, 15–19). In sharp contrast to the pursuits of the wicked, the prophet lifts the final triumph of the glory of the Lord that will be plainly known ‘as the waters cover the sea’ (v.14), when the Lord’s presence will command silence over all the earth (v.20).

References

Rabbi Nachman. 'Asur Lohayitiesh (Heb.)', Songs of Rabbi Nakhman of Breslov (Jerusalem: Gal paz)

Commentaries by Jin H. Han