Genesis 18

The Hospitality of Abraham

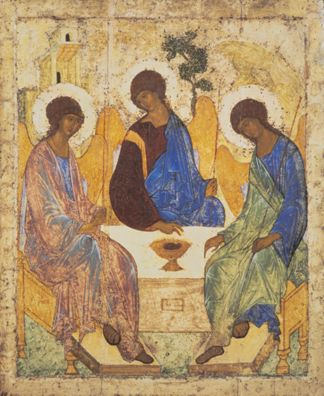

Andrey Rublyov

The Hospitality of Abraham (Icon of The Holy Trinity; The Old Testament Trinity), c.1420s, Levkas and tempera on panel, 142 x 114 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow / Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Place at the Table

Commentary by Aaron Rosen

Andrey Rublyov’s icon is a mystery. Theories abound about its date, patron, provenance, and even creator. It is only since the twentieth century that the icon’s original paint has been visible. For centuries, the icon was covered by a revetment (or riza), a protective metal plate attached by nails, whose holes are still visible in the wood. Moreover, the icon was continually ‘renewed’ by periodic repainting, a practice that brushes against the grain of contemporary Western notions of authenticity. But beneath all these layers of ambiguity lies an even more challenging theological enigma: who are these angelic figures, and what do they represent?

For centuries, Jewish and Christian commentators have puzzled over how to interpret the three strangers who arrive at Abraham’s tent. To the first-century Jewish philosopher Philo, this trio represented God, accompanied by his powers, while to the rabbis, God appeared with an angelic coterie. In the eyes of the second-century Christian writer Justin Martyr, the story revealed an early—albeit anonymous—entry of Christ into human history. Two centuries later, St Augustine would deliver a classic interpretation, reading the three visitors as representations of the Holy Trinity.

Rather than resolving competing interpretations, Rublyov’s icon entertains them. On the one hand, the three figures’ different gestures and garb encourage individual identifications, with the central figure often interpreted as Christ. As Rowan Williams notes, however, the figures’ identical faces and interlocking gazes might be more expressive of the dynamic of the Trinity, illustrating its ever-flowing interdependence.

Sometimes lost in such interpretations is the character of Abraham. Standing in front of this massive icon in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, I remember recognizing that these angels were not missing an Abraham; they were simply waiting for me—the viewer—to take up that role. Was I called to humbly serve the angels, or perhaps the icon itself? What hospitality could I offer before this sublime sight?

Marc Chagall

Abraham and the Three Angels, c.1960–66, Oil on canvas, 190 x 292 cm, Musée National Marc Chagall, Nice, France; MBMC6, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; Photo: Gérard Blot © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Hospitality on Trial

Commentary by Aaron Rosen

What is the best way to depict a dinner party? For Christian painters, the answer has been obvious. Whether the subject is the Last Supper or the Hospitality of Abraham, figures are almost always shown facing the viewer. Marc Chagall turns his back on this iconography. Throughout his career, he frequently returned to the story of Abraham and the angels. While he played with a number of arrangements, he consistently turns his angels away from the viewer. There is a puckishness to this choice, typical of an artist who prized his ingenuity, but also something more profound: Chagall deliberately avoids creating a devotional relationship between the viewer and the angels. They are never presented as a Holy Trinity. Instead, our eyes are drawn to Abraham standing at the far left of the composition, who returns our gaze. We cannot help feeling a bit like uninvited guests, travellers who have arrived too late and find the table full and the host exhausted.

Chagall makes other adjustments, too. In an earlier version, Chagall included the binding of Isaac in the top right of his composition, echoing images from the sixth-century mosaics in San Vitale, Ravenna, and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s fifteenth-century bronze reliefs for the doors of Florence Baptistery. From a Christian perspective, pairing the two scenes makes perfect sense: the angels represent the Trinity and the Sacrifice of Isaac prefigures the Crucifixion. This may be precisely why Chagall omitted this event in the later work. Instead, he depicts the angels descending toward Sodom at the upper right. The linking of the hospitality story with the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 19) follows biblical chronology more closely. Just as importantly, it raises questions that have historically concerned Jewish commentators. The angels’ visit demonstrates Abraham’s personal hospitality. The Sodom story, though, puts his charity to a more global test. We know the patriarch will open his home to strangers, but will he stick up for people of ill repute? Chagall’s image emphasizes the connection between personal and social duties. We must stick out our necks, even—maybe especially—for those who can’t possibly be angels.

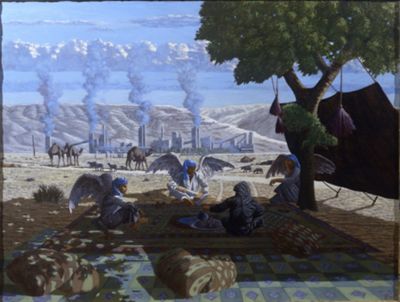

Roger Wagner

Abraham and the Angels, 2002, Oil on board, 92 x 122 cm, Collection of the artist; © Roger Wagner

A Picnic on the Edge of Doom

Commentary by Aaron Rosen

Like Stanley Spencer before him, the English artist Roger Wagner has a gift for seeing the Bible in everyday life. When Jesus walks on water, it is on the River Thames, beneath the shadow of the Battersea Power Station in London. And Golgotha is defined not by a hill, but Didcot Parkway’s mammoth cooling towers in Oxfordshire.

In fact, power lines—physically and metaphorically—run throughout Wagner’s work. When he first imagines Genesis 18, Wagner sets Abraham and the angels at the edge of a wheat field in his native Suffolk. The scene is far from bucolic, though. In the background, the hulking facade of the Sizewell nuclear power station glows eerily, reminding us of its toxic contents. In the artist’s words, this is ‘a picnic on the edge of doom’. In the biblical text, the angels are agents of destruction, on their way to Sodom and Gomorrah. In Wagner’s image they look more like potential victims, pleasantly chatting while a man-made catastrophe looms.

Sixteen years later, Wagner painted another image of Genesis 18. This time he found inspiration during his travels through the Middle East. According to Wagner, the picture ‘grew directly out of the experience of Bedouin hospitality’ in a desert encampment. And yet there is still an ominous edge to this composition. The nuclear power plant is replaced by the belching smokestacks of a cement factory, which he observed during a trip through Syria. Here too, there is little suggestion that the assembled angels are on a mission of vengeance. With humanity content to execute itself under a cloud of sulphur, who needs angels to supply the fire and brimstone?

If human destruction lies on the horizon, however, hope remains in the foreground. Abraham’s winged visitors remind us of our own better angels. In the end, what is most divine in this picture is Abraham’s generosity: his boundless concern for strangers.

Andrey Rublyov :

The Hospitality of Abraham (Icon of The Holy Trinity; The Old Testament Trinity), c.1420s , Levkas and tempera on panel

Marc Chagall :

Abraham and the Three Angels, c.1960–66 , Oil on canvas

Roger Wagner :

Abraham and the Angels, 2002 , Oil on board

A Spirituality of Feasting

Comparative commentary by Aaron Rosen

God repeatedly promises Abraham that his descendants will be innumerable, like the stars of the sky or the grains of sand on the seashore (Genesis 15:5; 22:17). The same might be said of Abraham’s artistic legacy. Depictions of even just a single episode of his life, the visit by the angels, are almost too numerous to count. Within Christian tradition, we might mention such masterpieces as the late antique mosaics at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and at San Vitale, Ravenna; medieval manuscripts such as the Vehap’ar Gospels and the Psalter of St Louis; Ghiberti’s Renaissance reliefs; and Baroque paintings by Carracci, Murillo, Rembrandt, and Tiepolo. While there are fewer Jewish images, there is an intriguing example in the influential Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695, illustrated by Abraham ben Jacob. The scene is highly unusual for a haggadah, which might be explained by the background of the artist, a Christian pastor who converted to Judaism. Examples of Abraham’s angelic visitation—mentioned four times in the Qur’an—can also be found in Islamic art, such as the early fourteenth-century Jami al-Tawarikh (‘Universal History’) composed by Rashid al-Din, a convert from Judaism to Islam. It seems fitting that a story about welcoming strangers has produced an abundance of overlapping and intersecting images, not easily confined within a single religious, cultural, or artistic context.

The works of Andrey Rublyov, Marc Chagall, and Roger Wagner provide a snapshot of this diversity. Together, they compel us to think through the experience of Abrahamic hospitality from multiple vantage points. We are, by turns, host, guest, and observer. Each of these roles attunes us to different questions and responsibilities. There is one question in particular that often gets lost in theological inquiries: what is the place of enjoyment in hospitality? Chagall’s image is the most straightforwardly celebratory. The angels in his canvas eagerly tuck into their food and drink, gesturing heartily as if guffawing at a joke. Indeed, laughter is at the core of the biblical narrative. Sarah’s snigger at the angels’ news that she will give birth anticipates her son’s name: Isaac (Hebrew: ‘he laughed’). As the French philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) insightfully adds, Isaac is not only born of laughter, he is ‘the one who comes to make them laugh’, to lighten Sarah and Abraham’s old age. Laughter is a genuine, joyful response to the befuddling revelations which an encounter with the Divine might bring. Sarah is fittingly resplendent, as if her body has already responded to the good, literally in-credible news brought by the angels.

There might not be laughter in Rublyov, but there is a sublime comfort which comes from contemplating this icon. Its nearly life-size dimensions and the almost circular arrangement of the angels’ bodies seem to enfold and protect the viewer. We might be in the position of Abraham, but it is the angels who seem to offer the greatest hospitality, as if inviting us to shelter under their gilded wings. Wagner’s canvases, to be sure, have foreboding elements, but that hardly means there is no joy in what the artist playfully calls Abraham’s ‘picnic’. In his painting from 2002, there is a humble camaraderie between the patriarch and his visitors, who all sit cross-legged on the carpet. Having come from the white-hot desert beyond, we can sense the angels’ relief as they drink in the dappled shade from the tent and oak tree. For all their differences, Rublyov’s, Chagall’s, and Wagner’s paintings each speak to the joys of hospitality, for host as well as guest. And, at a fundamental level, from the serene gold of Rublyov to the rich red of Chagall and the tranquil blue of Wagner, all three painters provide a feast for the eyes.

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1906–95) insists that true hospitality demands that we recognize an infinite and asymmetrical responsibility to others. We are not called simply to treat the Other as we would want to be treated, he says, but to ‘take up a position in being such that the Other counts more than myself’. The artists we have looked at do not undermine this message, but they do provide an important counterbalance. They remind us of what theologian David Ford calls the ‘spirituality of feasting’, the potential to luxuriate in the presence of both the Other and the Divine—or indeed the Divine within the Other. Joy and obligation can co-exist. Art encourages us to paint a vibrant picture of hospitality for ourselves, attuned to the pleasures which bind us together.

Commentaries by Aaron Rosen