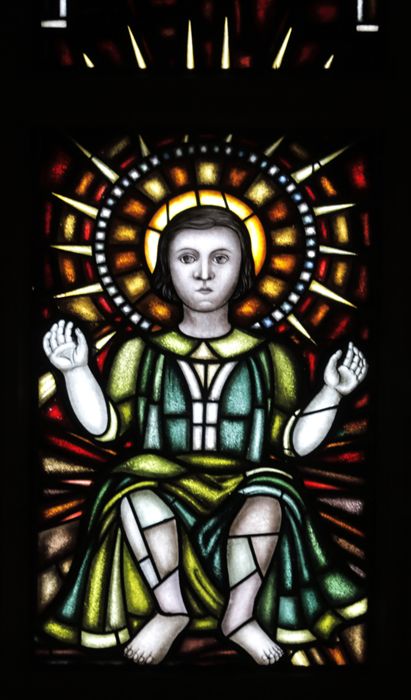

Francisco de Goya

The Drowning Dog, 1820–23, Mixed method on mural transferred to canvas, 131 x 79 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; P000767, Copyright of the image Museo Nacional del Prado / Art Resource, NY

‘Beginning to Sink’

Commentary by Johann Hinrich Claussen

Faced with some works of art, you can find yourself completely unclear about what the artist wanted to express in them. That is frustrating at first, but then it gives you the freedom to focus on your own perceptions. What do I see in this painting?

Francisco de Goya’s painting of a dog’s head is enigmatic. It belongs to the so-called ‘black paintings’ with which he decorated his country house Quinta del Sordo. Having acquired the property in 1819, he created fourteen paintings of great inscrutability on its walls—just for himself and his few visitors.

The series offers a nightmarish panorama that can hardly be interpreted. Single human figures or groups of people in strange connections and contortions show the monstrosities of humanity as though in a ‘satanic mass’ of visual art.

The painting of a dog’s head is an exception. It is neither monstrous nor charged with mysterious references. It only shows a dog’s head. But it is as difficult to understand as it is simple in appearance. Was it easier to decipher it in its original state? Historical photographs from the Quinta show that Goya had originally placed the dog in a landscape with a high rock in front of it, birds flying in the sky, at which the dog’s gaze was directed. All this is lost. Now the head alone survives, surrounded by fields of yellow-brown colour. Everything that could provide context is erased. Is the dog hiding behind a hill, is it buried in sand, or is it struggling in brown water—sinking into a dark wave? And what does its expression communicate: is it fearful or hopeful?

Whatever Goya wanted to express in his original composition, what I see here now is an endangered creature, all alone, surrounded by a brown nothingness—a desert of sand and ashes or a hostile sea that threatens to bury or to drown it. But it keeps its head up, looks straight ahead, seeming to expect something that will rescue it—perhaps even seeing it already.

This dog seems to me to be more expressive of the human condition than all the other figures in the ‘black paintings’. And it is this condition that Peter gives voice to with his words: ‘Lord, save me!’ (Matthew 14:30).

References

Hofmann, Werner. 2003. Goya: ‘To Every Story There Belongs Another’ (London: Thames & Hudson)