Ezekiel 37:15–28

Ezekiel’s Two Sticks

Ronald B. Kitaj

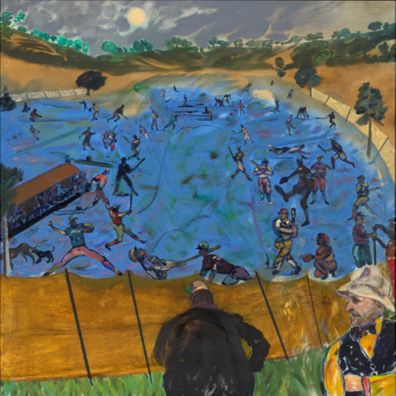

Amerika (Baseball), 1983–84, Oil on canvas, 147.32 x 147.32 cm, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut; Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933, Collection, 2006.52.14, © R.B. Kitaj Estate; Photo: Yale University Art Gallery

A Great Gulf Fixed

Commentary by Christina Juliet Faraday

Ronald B. Kitaj turned Jewish exile into an artistic mission, declaring himself a ‘Diasporist painter’ and writing not one but two Diasporist Manifestos.

Diasporism was not, he argued, uniquely Jewish, but the Jewish experience of uprootedness was one of many layers of exile that infused Kitaj’s works. In the first instance, however, Amerika (Baseball), shows Kitaj exploring his own separation, not from a scriptural ‘promised land’, but his American birthland. He paints from the nostalgic perspective of a self-imposed exile in England: ‘[f]rom time to time I have to make a baseball painting to express a deep national love’ (Morphet et al.: 1994: 150).

The title betrays the painting’s emigratory themes, referring to Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel Amerika, which opens with a description of the enforced emigration of a young man from Europe to New York. Meanwhile, as Aaron Rosen has noted, baseball features repeatedly in Jewish–American works of Kitaj’s generation as a symbol of aspirational belonging (Rosen 2009: 101 n.74 and Appendix 3).

Beyond this, any unity that the painting might appear to have is illusory. The picture plane is fragmented: there are too many pitchers, too many batters, no ‘home plate’. The lack of compositional harmony mirrors the disjointedness of Kitaj’s relationship with his birthland. Rosen sees this as Kitaj’s meditation on ‘homelessness’ (ibid: 91).

This loss of a shared home, inhabited by peoples with shared forebears and a shared history, is the state that Ezekiel’s symbolic sticks promise to resolve.

Rosen suggests that the emptiness of the central field evokes the Red Sea of Exodus 14: dangerous, but also salvific (ibid: 91). The gap also speaks of another gulf, the transatlantic one that physically distanced Kitaj from the America he considers so nostalgically here. In the bottom right a figure, seemingly a self-portrait, looks off to the side, separated from the hubbub, suggesting Kitaj’s conflicting feelings towards his homeland.

As with Ezekiel’s sticks, which signify what will be done, any resolution—any homecoming—is deferred. Exile may be a state of freedom, as well as of trauma and anticipation.

References

Kitaj, R. B. 1989. First Diasporist Manifesto (London: Thames and Hudson)

———. 2007. Second Diasporist Manifesto (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2017. ‘Home and the World’, in Artists in Exile: Expressions of Loss and Hope, ed. by Frauke V Josenhans (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Morphet, Richard et al. 1994. R. B. Kitaj: A Retrospective (London: Tate Gallery)

Nochlin, Linda. 1996. ‘Art and the Conditions of Exile: Men/Women, Emigration/Expatriation’, Poetics Today, 17.3: 317–37

Rosen, Aaron. 2009. Imagining Jewish Art (London: Routledge)

Unknown Chinese artist

Kangxi vase, Late 17th to early 18th century, Porcelain, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Nothing So Damaged That It Cannot Be Repaired

Commentary by Christina Juliet Faraday

In January 2006 a visitor to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, UK, tripped and tumbled down a grand stone staircase, his fall broken by the three Kanxi vases on a windowsill at the foot of the stairs. The vases shattered into thousands of fragments: anyone looking at the twenty-four trays and many small bags collected after the incident would have been forgiven for thinking the repair impossible.

Yet, astonishingly, specialist conservator Penny Bendall was able to sort the fragments and reassemble the vases in eight hours, a miracle of conservation and patience.

Ezekiel’s gesture of joining two sticks is heightened by the seeming impossibility of the reunion he describes. It is a union of the southern remnant of the original twelve tribes of Israel (Judah and Benjamin)—who had formed the kingdom of Judah and were now in exile together in Babylon—with the other ten tribes (vv.15, 19)—once part of the northern kingdom of Israel, now dispersed among the peoples who invaded them. The repaired vase could equally stand for the miraculous restoration and reparation of the breaks experienced by the tribes during their separations and scatterings.

As a Qing Dynasty vase in an English collection, the object might itself seem to be in a kind of exile. However, such vases were usually made for the European export market, their exotic motifs designed to attract wealthy customers looking for objects to fill their stately homes and demonstrate their taste and status. Although the vase, therefore, can’t be seen in terms of forced separation from its culture, the wealth that enabled its purchase in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries may itself have come more or less directly from the profits associated with the displacement of people in the transatlantic slave-trade. Issues of exclusion and separation run deeper than the cultural displacement of the jar’s enamel birds, waterfalls, and butterflies.

The joining of the two sticks signifies, not only the reunion of the tribes of Israel, but also their purification, salvation from ‘backslidings’ in preparation for a renewed relationship with God (v.23). However disastrous the situation, the vases stand as a reminder that nothing is so broken that it is beyond repair, if we only know where to look for help.

Andy Goldsworthy

Two forked branches and twig. Ilkley Moor, Yorkshire. September 1978, 1978, Cibachrome photograph, 24.2 x 16.2 cm, The Arts Council of Great Britain; © Andy Goldsworthy; Photo: Courtesy Andy Goldsworthy Studio

Miracle as Metaphor

Commentary by Christina Juliet Faraday

Ezekiel’s two sticks are as much metaphor as miracle.

Their miraculous aspect lies not only in the gesture of joining the two sticks in the hand, but also in the future fulfilment of the prophecy they symbolize: that the ten northern tribes of Israel, scattered among and intermarried with those who invaded them, will one day be reunited with the two southern tribes of Judah and brought back to their God-given lands.

But the choice of wooden sticks to express this unity has other resonances: in horticulture, inosculation is the practice of binding branches together so that the bark wears away, causing the underlying cambium to combine and graft the branches together. This process can happen naturally, but has also been exploited artificially to create intricate and prodigious shapes.

Is inosculation what we are seeing in Andy Goldsworthy’s ‘Two forked branches and twig’? The stick emerges from the ground, like lightning in reverse, forking only to join again in a single loop. The straightness of the apex suggests they may have been tied, rather than grafted, together, but the haze of the photograph doesn’t allow us to see for sure how the branches join at the top.

Goldsworthy has performed a similar ‘miracle’ to Ezekiel’s, though without the presence of the hand.

Although no person is visible in this photograph, the question of an external influence, of mastery, is suggested by the unnatural melding of the branch, much as God’s prophetic gloss on Ezekiel’s actions suggests an external influence in human affairs.

Metaphor returns alongside miracle. Goldsworthy’s exploration of transience, the traces of human presence in the landscape and the issues they raise about power and ownership, are pertinent to Ezekiel’s discussion of homeland and exile. The promise of the tribes’ reunion in ‘their own land’ can be interpreted geographically, but also spiritually, looking forward to a time when human disputes about land ownership will be subsumed into a greater, but as yet invisible, kingdom

Ronald B. Kitaj :

Amerika (Baseball), 1983–84 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Chinese artist :

Kangxi vase, Late 17th to early 18th century , Porcelain

Andy Goldsworthy :

Two forked branches and twig. Ilkley Moor, Yorkshire. September 1978, 1978 , Cibachrome photograph

Fixed Sticks and Shattered Matter

Comparative commentary by Christina Juliet Faraday

In his Second Diasporist Manifesto, the artist Ronald B. Kitaj enumerated some aspects of Jewish art, identifying fragmentariness as a recurring feature:

395 Jewish Art may sometimes prefer a montage of fragments ...

396 Jewish Art is a shattered history. One wants to mend it into new life.

397 Jewish Art makes the unified work of art a sort of idolatry

(Kitaj, Second Diasporist Manifesto, 2007)

In Ezekiel 37 the themes of separation, fragmentation, union, and reunion are likewise to the fore. Ezekiel takes two sticks, and joins them in his hand: their divinely-ordained labels symbolic of the scattered tribes of Israel. Ezekiel combines two sticks to figure the (re)union of peoples, with each other, but also with a restored land, and ultimately with God. In each of these works we find fragmentation, but also exclusion, separation, and reunification.

In the vase, shattered, scattered, and mended, reunification is the result of an unforeseen disaster, miraculous, but still a making-the-best-of, which sets it against the return to God, which is to be superior even to Eden in its everlastingness: ‘when my sanctuary is in the midst of them for evermore’ (v.28). In the looping sticks of Andy Goldsworthy’s photographed sculpture, separating and converging, the divergence is really part of a closed loop, circular, forever returning. In these artworks we find a reflection of Ezekiel’s combinatory metaphor, and the reunion of scattered and divergent peoples promised in God’s prophecy. In both cases external forces are seen to create the conditions for restoration: the need to look outside the artwork, or outside oneself, for help.

The suggestion of exile is deeply embedded in Kitaj’s work, reunion deferred to a future point like the promise held out by Ezekiel in the figure of the two sticks. The prophecy is in the future tense. In Amerika (Baseball) a figure, probably Kitaj’s self-portrait, looks across the picture plane, separated from the disjointed and fragmentary baseball field, evoking the ‘Wandering Jew’s’ perpetual state of displacement (Zemel 2008: 178).

Meanwhile, Goldsworthy’s transient ‘land art’—recorded in photographs—questions what it is to ‘own’ an artwork, and by extension, anything natural, from a stick to a piece of land. The fraught issue of land ownership is still present in questions of Jewish exile and homecoming, but while Ezekiel’s verses speak of ‘the land where your fathers dwelt that I gave to my servant Jacob’ (v.26), there is also the spiritual aspect of God’s eternal presence ‘when my sanctuary is in the midst of them for evermore’ (v.28).

Much like the strange perspective of Kitaj’s baseball field, in which the ground seems to shift uneasily as the eye ranges across its surface, Ezekiel’s verses seem to look now at one distance, now at another. The labelling of the sticks (v.16) recalls Numbers 17, when Moses is directed to write the name of each tribe of Israel on one of twelve rods. In this sense the passage looks back, like Kitaj’s nostalgic alter-ego recalling a scene of baseball from his childhood. Meanwhile, the ‘everlasting covenant’ (Ezekiel 37:26) looks forward, to a geographical and spiritual homecoming. We find this sense of eternity driving even Kitaj’s secular anxiety for immortality: ‘Diasporism is, after all, an attempt to survive via art, and a little beyond death, maybe’ (Kitaj 2007: point 142).

This passage presents a highly visual symbol and then consciously glosses it with a prophecy. ‘When the sticks on which you write are in your hand before their eyes, then say to them...’ (vv.20–21). The passage offers both image and interpretation, drawing out the meaning of the symbol for the edification of Ezekiel’s audience. In this sense, it might well stand for the possibilities of the visual arts for theology: the ability of things in the world, human-made, or human-arranged, to point to things beyond the world, and reveal the working of the divine. This use of the physical world, in verses pre-dating the Incarnation, offers a pre-Christian redemption of matter, or as Kitaj puts it: ‘[my pictures] may be likened to Jewish IDEAS, or even Jewish MATTER. It is the case that the MATTER MATTERS!’. Images can point to divine truths, as Ezekiel knew only too well.

References

Keil, Carl Friedrich and Franz Delitzsch. 2001. Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament, vol. 10, rev. edn (Peabody: Hendrickson)

Kitaj, R. B. 2007. Second Diasporist Manifesto (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2017. ‘Home and the World’, in Artists in Exile: Expressions of Loss and Hope, ed. by Frauke V Josenhans (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Zemel, Carol. 2008. ‘Diasporic Values in Contemporary Art: Kitaj, Katchor, Frenkel’, in The Art of Being Jewish in Modern Times, ed. by Barbara Kirschenblatt–Gimblett and Jonathan Karp (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), pp. 176–91

Commentaries by Christina Juliet Faraday