Numbers 17

Aaron’s Rod

Kaspar Schockholz

Aaron before the Altar, 1446, Wood, Choir stalls, Merseburg Cathedral, Germany; Courtesy of G. Freihalter

A Great High Priest

Commentary by Laura Llewellyn

This carved relief is one of twenty-two tall rectangular panels, each possessing a similarly pleasing simplicity in their design, which form the backs of two sets of choir stalls in the Cathedral of Merseburg, in Saxony-Anhalt (part of Old Saxony). Of the artist, we know only what we can glean from his signature—prominently displayed on the stalls on the choir’s south side—that he was a Dominican friar, called Kaspar Schockholz.

The core narrative of the panels is the Life and Passion of Christ. However, each scene from this cycle is flanked on either side by an episode which predates (and in some way pre-empts) the life of Christ. The image of Aaron with his miraculous rod is located to the left of the Nativity of Christ, to the right of which appears the non-biblical episode of the Emperor Augustus’s Vision of the Virgin and Child with the Tiburtine Sibyl. For this format, Schockholz almost certainly took inspiration from a ‘biblia pauperum’, a popular type of printed book at the time, in which scenes from the Old and New Testament were grouped together to show typological frameworks.

Despite having been included within the cycle as a prophecy of the coming of Christ, in the imagery of this specific panel the artist paid close attention to Aaron’s role as high priest. He stands alone before the altar wearing the distinctive headdress of a Jewish priest, as anachronistically conceived in fifteenth-century terms. He holds his left hand against his chest in a manner which suggests that the blessing made by his other hand is directed, in part, at himself. With his blessing hand, he also signals toward the sprouting rod on the altar behind him, though his eyes remain trained on the viewer.

With this subtle economy of gaze and gesture, Schockholz gives visual form to the particular significance of the rod as symbol of the divinely-endorsed priesthood. It is an apt emphasis on the priestly vocation, given Christ’s status in Christian tradition as the true and eternal High Priest. In this respect Aaron is his forebear, as he is of all those who will share Christ’s priestly ministry.

References

Cottin, Markus, John Uwe, and Holger Kunde. 2008. Der Merseburger Dom und seine Schätze: Zeugnisse einer tausendjährigen Geschichte (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag), pp.184–86

Unknown Master

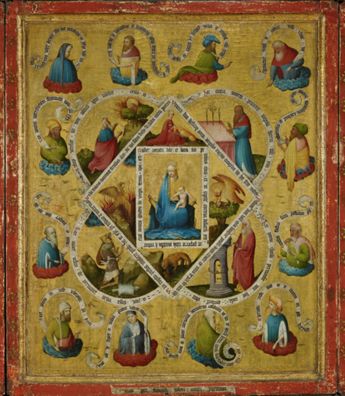

Altarpiece with the Glorification of Mary’s Perpetual Virginity, c.1420–23, Panel, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn; © LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn; photo: Jürgen Vogel

Purity and Parity

Commentary by Laura Llewellyn

Aaron’s rod which bloomed without roots or water, was likened to the Virgin by all four Doctors of the Western Church. Virga is the Latin word with which Jerome translated the Hebrew matteh, and the poetic effects offered by the linguistic similarities of virga and virgo were seized upon by countless other interpreters of the Scriptures through the ages.

The inscribed rectangle in the middle of the central panel of this fifteenth-century altarpiece shows the Madonna and Child enthroned surrounded by symbols of Christ and scenes and figures from the Old Testament. The preponderance of inscriptions leaves little doubt as to the painting’s didactic function, and the inscription on the lower part of the engaged frame, underwriting all the rest, proclaims its overall theme: Hanc per figuram noscas castam parituram (‘Learn of the Virgin birth through this painting’). It is clear from the many vignettes, both textual and figural, that the Virgin birth is to be understood not only as the miraculous conception of Christ, but also the perpetual virginity of Mary. Saints Jerome and Augustine, both of whom wrote treatises in defence of this doctrine, appear in the wings of the altarpiece holding scrolls which proclaim it.

Despite this focus on Mary’s purity, Christ is also foregrounded in the imagery. Four triangles surrounding the Madonna contain symbols relating to his Passion and Resurrection—the pelican who pierces her breast to feed her chicks, the lioness whose cubs awake on the third day, the phoenix who rises again, and the unicorn tamed by a virgin.

These scenes are encased within a quatrefoil of four semi-circles containing scenes from the Old Testament. Aaron appears in the upper right, kneeling before the altar, his gaze trained upon his budding rod. As with the altarpiece’s overall imagery, the depiction of Aaron proclaims the miracle of the Virgin birth while also celebrating Christ, the fruit of her miraculous fecundity.

The inscription Hec contra morem produxit virgula florem stresses the parity between the rod and the Virgin’s womb.

References

Das Rheinische Landesmuseum. 1977. Auswahlskatalog 4: Kunst und Kunsthandwerk: Mittelalter und Neuzeit (Bonn: Rheinland-Verlag), pp. 53–58

Unknown artist

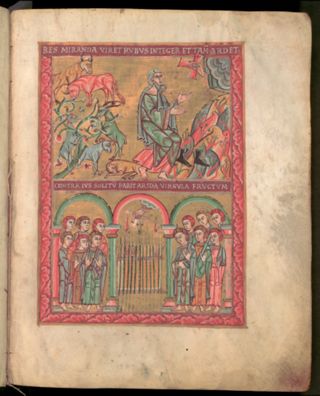

Coronation Gospels of Vratislav II (The Vyšehrad Codex; The Coronation Codex), 1070–86, Illumination on parchment, 41.5 x 32 cm, Národní knihovna České republiky, Prague; MS XIV.A.13, fol. 4r, Photo courtesy of National Library of the Czech Republic

Chosen by God

Commentary by Laura Llewellyn

Against the customary law, a small withered rod bears fruit (Contra ius solitu[m] parit arida virgula fructum).

The miracle of Aaron’s sprouting rod appears with this inscription above it on the fourth folio of the celebrated Coronation Gospels of Vratislav II of Bohemia. It is presented together with three other Old Testament scenes (two of them on the verso, representing the closed gate of Jerusalem from Ezekiel 44:2 and the Tree of Jesse drawn from Isaiah 11). It is preceded by three folios that include portraits of the Evangelists followed by a complete genealogical tree of Jesus Christ, and immediately followed by Matthew’s Gospel with its lengthy description of Christ’s lineage from Abraham. Sandwiched between imagery and texts which are specifically concerned with Christ’s ancestry, the four Old Testament types are then clearly to be understood as Christ’s forebears.

In the lower register of folio 4r, Aaron’s rod, placed centrally among the others before the sanctuary’s altar, has miraculously bloomed, with new shoots along its length and buds sprouting at its apex. Numbers 17 specifies that Moses alone took the rods into the sanctuary and brought them out again the following day to reveal the miracle. But here the twelve heads of the Israelite tribes look on with their hands, where visible, raised in wonder. The haloed hand of God emerging from a cloud suggests that the miracle is taking place before their very eyes, though the triple-arched structure that subdivides the scene ensures that they remain outside the bounds of this hallowed space.

The conflation of the two moments—the overnight flowering of the rod and the discovery of the miracle the next morning—facilitates a parallel with the scene of Moses at the burning bush (Exodus 3–4) in the register above where, again, God’s hand appears from on high. This repeated motif, along with the inscriptions, emphasizes the miraculous nature of the events and, especially, the concept of divine election.

An enthroned halo-less figure, depicted in the historiated initial on folio 68r of the manuscript, receives the same blessing from on high. He has sometimes been interpreted as King Vratislav himself, for whom this manuscript was made. Newly crowned as King of Bohemia, he is shown as an inheritor of the legacy of the divinely elected leaders of the Old Testament.

References

Hayes Williams, Jean Anne. 2000. ‘The Earliest Dated Tree of Jesse image: Thematically reconsidered’, Athanor 18: 17

Kaspar Schockholz :

Aaron before the Altar, 1446 , Wood

Unknown Master :

Altarpiece with the Glorification of Mary’s Perpetual Virginity, c.1420–23 , Panel

Unknown artist :

Coronation Gospels of Vratislav II (The Vyšehrad Codex; The Coronation Codex), 1070–86 , Illumination on parchment

King, Prophet, and Priest

Comparative commentary by Laura Llewellyn

The miracle of Aaron’s rod, which flowered overnight and bore ripe almonds, offers an antidote to the murderous retribution on those who had rebelled against the priestly authority of Aaron and his sons, described in the preceding chapters. With each rebellion, Moses determined to let the will of God prevail. And yet, when great numbers of rebels met with their death it only served to stimulate further dissent as Moses and Aaron were personally blamed for killing the Lord’s people.

Against this backdrop of punitive fire, plague, and burial alive, the miraculous blossom of Aaron’s rod reveals a life-giving and benevolent divine force. And yet, it is the rod which incites the people’s terror, who at last acknowledge that unrestricted access to the tabernacle of the Lord has fatal consequences and accept the elevated status of the Levites as ministers of the sanctuary.

Even before Aaron’s staff is placed inside the tent of the testimony, we have encountered it several times already (though whether the rod that blooms is the very same one described in earlier passages is a debate for another day). During the liberation of the Israelites from Egypt, Aaron’s rod is the channel for God’s power: turning the water of the Nile to blood (Exodus 7:19–20), summoning plagues of frogs and gnats (8:16–17), or transforming into a snake and devouring all the other staffs-turned-serpents which belong to the Pharaoh’s sorcerers (7:8–12). In contrast, in Numbers 17, this instrument of miracles becomes the object of one—and, crucially, in Aaron’s absence, thereby calls attention to the fact that Aaron has not chosen his role, but has been summoned to it by God. The rod is not wholly subject to Aaron’s individual will. The Hebrew word matteh which describes the tribal rods means ‘staff’ but also ‘tribe’ and ‘branch [of a vine]’. This wordplay is used carefully to foreground the genealogical inevitability of the Levites’ collective claim on the priesthood. They are a chosen people, existing apart from the other tribes as mediators between the people and an all-powerful God.

The earliest Christian commentators interpreted Aaron’s rod as a prefiguration of the resurrected Christ, who blossomed to life following his death on the wooden cross. The rod was also understood to bear witness to the budding stump of Jesse (cf. Isaiah 11), itself a prophecy of the coming of the Messiah.

In the Christian visual tradition, the iconography of Aaron’s rod is most commonly employed to foreshadow the Virgin birth and is often grouped together with other Old Testament episodes which were deemed similarly prophetic since they all feature the motif of a thing that remained untouched: Moses and the burning bush (which burned but was not consumed; Exodus 3), Gideon’s fleece (dry despite the dew all around it; Judges 6:36–40), and the closed gate of Jerusalem (which remained shut after the Lord had passed through it; Ezekiel 44:2). Such imagery proliferated especially in German territories during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (e.g. a diptych in Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza; Inv. no. 272 (1929.18.1), and an embroidered hanging in the Met Cloisters; Inv. no. 69.106).

The Vyšehrad Codex was probably given to King Vratislav II of Bohemia on the occasion of, or shortly after, his coronation of 1085. The depiction of Aaron’s rod early in the manuscript is explained by its twofold significance—as a reminder that the priestly elite are divinely elected, and as prefiguring the ‘fruit’ of the Virgin birth, Christ. The emphasis on a preordained genealogy offers a legitimizing context for the reign of the newly crowned monarch, who like Aaron was divinely elected. It is also a visual precursor to the subsequent pages of the manuscript which consists chiefly of extracts from the Gospels, with twenty-nine illuminated scenes from the life of Christ.

A similar inference regarding the continuity from Old to New Testament underlies the imagery of the Cologne altarpiece, though here the genealogical aspect seems less important and the rod’s prophetic implications in relation to the Virgin’s womb are underscored. This is unsurprising given the altarpiece’s provenance from a church dedicated to the Virgin.

Finally, the carved relief in Merseburg Cathedral, though certainly included in the cycle for its prophetic connotations, stands out from other traditional Christian depictions of Aaron for the special attention to his status as High Priest, a fitting emphasis given the priestly occupants of the choir stalls below.

Commentaries by Laura Llewellyn