Psalm 22

A Great Cry

James Tissot

What Our Lord Saw from the Cross (Ce que voyait Notre-Seigneur sur la Croix), 1886–94, Opaque watercolour over graphite on grey-green wove paper, 248 x 230 mm, Brooklyn Museum; Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.299, Brooklyn Museum / Bridgeman Images

Participation in Suffering

Commentary by Junius Johnson

James Tissot’s watercolour reverses the perspective that is the norm for images of the crucifixion. Rather than gazing upon Christ, and therefore standing in the position of the scoffers, or, at best, the bewildered apostles or the grief-crippled and faithful women, Tissot gives us Christ’s eyes; asks us to enter in to the experience of the Lord. In this aspect the image is suited to the illumination of the specific section of Psalm 22 in which the Psalmist looks upon his enemies encamped around him.

The bulls of Bashan (Psalm 22:12), mentioned also in Deuteronomy 32:14 and Amos 4:1, are often interpreted as a sign of the rich and powerful (e.g. see eighteenth-century commentaries by Matthew Henry and Charles Wesley). The reason is that bulls from Bashan were especially fat and strong (Craigie 1983: 200). Proverbs 28:15 compares wicked rulers to lions and the term dog was used throughout the Hebrew Bible to refer to those of low social standing or to someone contemptible (e.g. 2 Kings 8:13; 2 Samuel 9:8).

All of these human types are in evidence in the various individuals assembled at the foot of the cross. Also present in Tissot’s composition are the women mentioned in Matthew 27, a lone figure who is likely to be the Apostle John, and, front and centre, the mother of the Lord.

The reversal of perspective does not allow us to gaze on the one who has been pierced hand and foot, who is wracked with thirst, and whose bones are out of joint. All we see of the body of Christ are his feet. We are instead asked to consider all these indignities not as a spectacle we contemplate but as our own experiences. If we look with Christ’s eyes, then we must contemplate the wounds with Christ’s body: that is, as if our body were his, as if it is we ourselves who are crucified. As such, this painting completes the theological picture, for while we are the mockers, we are also crucified with Christ (Galatians 2:20). This is the same unity of perspective to which the Psalm invites us: that we may also feel ourselves, with the Psalmist, dried up and laid in the dust of death.

References

Craigie, Peter C. 1983. Psalms 1–50, Word Biblical Commentary, 19 (Waco: Word Books)

Henry, Matthew. [1706] 2009. Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible (Peabody: Hendrickson)

Wesley, John. 1765. Explanatory Notes on the Old Testament (Bristol: William Pine)

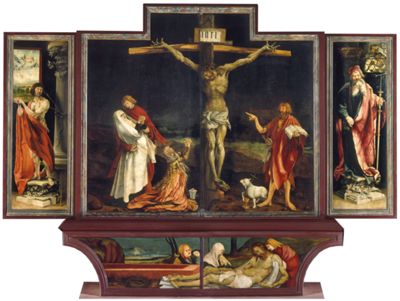

Matthias Grünewald

The Isenheim Altarpiece; Closed altarpiece: Saint Sebastian, the Crucifixion; Saint Anthony the Great; Predella, the Lamentation on the Body of Christ, 1512–16, Tempera and oil on wood, 376 x 534 cm (closed), Musée d'Unterlinden, Colmar; 88RP139, © Musée d’Unterlinden, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

The Loneliness of Desolation

Commentary by Junius Johnson

The Isenheim Altarpiece is among the most celebrated depictions of the crucifixion, and it serves as a thematic overview of the event seen by the Gospel writers as the fulfilment of Psalm 22.

For all those depicted, ‘trouble is near and there is none to help’ (Psalm 22:11). The emaciated and diseased body of the Lord and the agonizing contortion of his hands convey the brutality and intense suffering of the Lord’s chosen. To his left stands John the Baptist, himself a martyr, perhaps representing all of the Old Testament saints (as in Dante, where he sits at the head of those who looked upon Christ in faith as still to come, Paradiso 33.19–33). He performs his characteristic task: pointing to the Lamb of God. There is something ironic in his gesture, and in the quotation of his famous words: ‘He must increase but I must decrease’ (John 3:30, here in Latin), for in this moment the Baptist may look something of a fool and his pointing seem to be in line with the mockers. But this is the very moment to which he came to witness, to a Baptism greater than that in water. ‘Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world’ (John 1:29); but not as you expected.

To Jesus’s right stands his mother, collapsing into the arms of the Apostle John, with Mary Magdalene on her knees in supplication. These three are New Testament saints, but, as they have not yet experienced the resurrection of Christ, they have not yet become a people of hope. The moment of crucifixion, which will work life and hope for so many, is to them still an inexplicable failure.

Saint Sebastian on the viewer’s left and Saint Anthony on the viewer’s right witness that the life of the follower of Christ is also one of suffering and death: Anthony tormented by a demon, and Sebastian bound and pierced by arrows. Trouble is indeed near, and there is none to help.

Charlie Mackesy

Crucifixion, 2016, Charcoal on paper, Collection of the artist; © Charlie Mackesy

Dissipation and Exaltation

Commentary by Junius Johnson

Charlie Mackesy makes the striking decision to use a medium without colour. His charcoal drawing suggests the ephemerality of the body it represents (‘melting like wax’). Christ’s left arm seems to dissipate at the wrist, and the lines defining the contours of the body are difficult to fix. On Christ’s left side his body is mirrored behind him, like an after-image, as if the body is fading into the air, or impressing that air with Christ’s human form. It is as though not only Christ’s heart melts like wax (Psalm 22:14), but his entire body.

But what is most arresting about this drawing is Christ’s posture: he is not slumped in exhaustion nor limp in death, as so often in the art of the crucifixion. Indeed, his hands (and maybe his feet too) are no longer fixed to the cross at all. With his back arched and head thrown back (rather than lolling forward), one feels that Christ is being lifted up from the cross chest first. This Christ seems poised to bypass the grave and go straight to the ascension.

It is this posture that converses so fruitfully with verse 19 of the Psalm. Here, in a surprising shift, there is an announcement that out of the dark despair of the earlier eighteen verses, hope is able to spring. The ascension of the crucified Christ recontextualizes and reinterprets the cross much as the final section of the Psalm recontextualizes and reinterprets its beginning. The cross, as it is eclipsed by the body of Christ, becomes a path to glory, a jumping off point for the triumphant hero.

This drawing therefore presents a sign of victory that is neither simplistic nor apologetic. There is purpose to the cross, and this work reveals an inner dynamic that may also help us to discern what animates the Psalm: the character and purposes of the God who hearkens to the afflicted and redeems the lost. Just this dynamic connects the beginning of the Psalm to its triumphant ending—beyond every sense of abandonment, the one who trusts in the Lord may expect resurrection and ascension.

James Tissot :

What Our Lord Saw from the Cross (Ce que voyait Notre-Seigneur sur la Croix), 1886–94 , Opaque watercolour over graphite on grey-green wove paper

Matthias Grünewald :

The Isenheim Altarpiece; Closed altarpiece: Saint Sebastian, the Crucifixion; Saint Anthony the Great; Predella, the Lamentation on the Body of Christ, 1512–16 , Tempera and oil on wood

Charlie Mackesy :

Crucifixion, 2016 , Charcoal on paper

Abandonment, Hope, and Glory

Comparative commentary by Junius Johnson

Psalm 22, of David, is a heart-wrenching cry for help. The Psalmist sees himself beset on all sides by enemies and mockers.

It underwent a powerful transformation at the crucifixion, when Christ took its opening words into his own mouth in what has come to be known as the cry of dereliction: ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’ (Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:34). With the recitation of those words, Christ would have called the entirety of the Psalm to the minds of all devout Jews present. The similarity between the Psalm and the circumstances of the crucifixion are striking, and the Evangelists structure their accounts to make this plain: the mocking (Psalm 22:8; Matthew 27:43), the contortion of the body (Psalm 22:14), the piercing of the nails (Psalm 22:16), Christ’s thirst (Psalm 22:15; Matthew 27:34; Mark 15:23), the casting of lots for clothing (Psalm 22:18; Matthew 27:35; Mark 15:24). And yet for some reason, the crowd was not reminded of the Psalm at Christ’s recitation. When they hear the opening in Hebrew/Aramaic, (Eli, Eli: Matthew 27:47–49; Eloi, Eloi: Mark 15:35–36) they think that he is calling on Elijah.

The Psalm can be divided into three parts. In verses 1–11, the Psalmist is abandoned, scorned, and mocked by his people. The Isenheim Altarpiece offers one possible depiction of this section as applied to the crucifixion, not flinching from the horrors inflicted on Christ. In the second section (Psalm 22:12–18), the Psalmist is attended by beasts and evildoers who seek his life and torture him. Here James Tissot’s What Our Lord Saw from the Cross is especially striking, depicting the strange scene that greeted the dying Lord. In the third section (Psalm 22:19–31), the Psalmist reveals that in spite of his abandonment and torture, God has not in fact turned away, but hears the cry of the afflicted and is close by to help. This last section gives way to an expansive vision of praise. Charlie Mackesy’s Crucifixion supplies a somewhat ambiguous image here, on which more in a moment.

In the Christian tradition the Psalm has been interpreted as expressing that Christ on the cross felt cut off from the Father. This may be seen as the natural result of Christ bearing the sin of the world, being in that moment made into sin for us: God cannot look upon sin (Hebrews 1:13), and so when Christ becomes our sin, the Father must turn his face away. For some this means that true separation is introduced into the Trinity at this point, that the Son is indeed cut off from the Father and from the Holy Spirit; for others, this is true only of the human nature of Christ: it suffers damnation in that moment, exhausting the full divine wrath so that mercy may follow. It is in line with this sort of reflection that it has been called a cry of dereliction.

However, this traditional Christian reading does not take the whole Psalm into account: the third section cannot be reconciled with this type of claim. Indeed, the whole point of the Psalm is that God does not turn his face away:

For he has not despised or abhorred the affliction of the afflicted; and he has not hid his face from him, but has heard, when he cried to him. (Psalm 22:24)

The sense of loss and abandonment the Psalmist feels at the beginning is only that: his sense. The truth is that a salvation has been prepared for him so astonishing that it will summon the entire world to praise (vv.27–28). This final vision of a banquet of worship enfolds not just future generations (vv.31), but even the dead: ‘before him shall bow all who go down to the dust, and he who cannot keep himself alive’ (vv.29). In the words of the Lamb of God who is in the process of taking away the sins of the world on the cross, this Psalm is an announcement of redemption in Christ, the resurrection of the dead, and the glory of the world to come.

It is in an attempt to honour both the traditional Christian interpretation and the meaning of the text when taken as a whole that I have chosen Charlie Mackesy’s Crucifixion. It could be read in line with the traditional rendering, but it also gestures at something more, at a transcendent meaning to the crucifixion that exceeds what is clear from the event itself, and that thus makes space for the vision of salvation and praise with which the Psalm concludes.

Commentaries by Junius Johnson