1 Samuel 16:1–13

The Anointing of David

Unknown artist

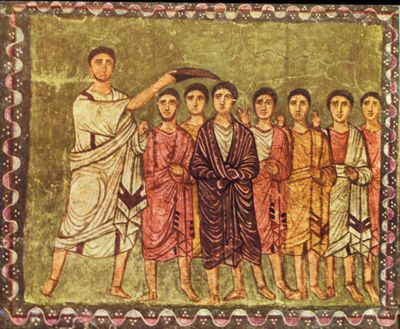

Samuel Anoints David, wall painting from the Dura-Europos Synagogue, 3rd century, Wall painting, National Museum of Damascus; www.BibleLandPictures.com / Alamy Stock Photo

God’s Saving Hand in History

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

The excavation of the synagogue at Dura Europos in 1932–33 was one of the great archaeological events of the twentieth century. The discovery of a second-century synagogue with fully painted walls depicting scenes from sacred history challenged long-held convictions about the Jewish prohibition of figurative art.

The walls of the synagogue are illuminated with a three-tiered pictorial cycle, painted in tempera, showing major moments in salvation history.

A picture with the Aramaic inscription ‘Samuel anoints David’ was located prominently, immediately next to the Torah shrine. It portrays David standing with his brothers, all dressed in Roman fashion in coloured tunics and cloaks (pallia). All have the same youthful facial features and short hair. On their right is a bearded figure with stripes (clavi) on his tunic, perhaps as a sign of rank. Presumably this is Jesse, the father. David is dressed in a cloak of purple, the imperial colour. Several figures raise their right hands in a gesture of acclamation. A much larger figure of Samuel holds a horn and anoints David on the head. Samuel too wears attire reserved for Romans of a high status: a white tunic with purple stripes and a white pallium.

The figures are painted in the manner of contemporary Graeco-Roman art. The image anticipates some of the features of Byzantine style, including isocephaly (heads at the same level) and stylized folds in the garments. All the figures are presented frontally, including Samuel, who faces the viewer rather than David. The poses are static and hieratic, the eyes stare straight ahead. The faces and clothing are all similar. No attempt is made at perspectival realism: the figures float on a uniformly coloured background.

These paintings were probably used for instruction. They illustrate the actions of God in Israel’s history. God could not be portrayed; but God’s action could. In a number of the wall images, an anthropomorphic hand of God is shown, indicating God’s activity. The stress on God’s action for Israel explains why it is Samuel, rather than David, who is given prominence in the anointing image: Samuel acts as God’s agent. The election of David is from God, as is the monarchy itself—despite God’s original anger at the Israelites’ desire to have a king (1 Samuel 8).

References

Gutmann, Joseph (ed.). 1971. No Graven Images. Studies in Art and the Hebrew Bible (New York: Ktav)

Milgrom, James. 1984. ‘The Dura Synagogue and Visual Midrash’, in Scriptures for the Modern World, ed. by Paul R. Cheesman and C. Wilfred Griggs (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University), pp.29–60

‘The Synagogue at Dura Europos’, https://chayacassano.commons.gc.cuny.edu, [accessed 15 October 2019]

Raphael

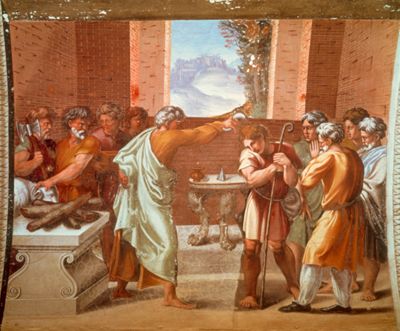

David is Anointed by Samuel, c.1519, Fresco, Raphael Logge of the Apostolic [Vatican] Palace, Vatican City; akg-images

The Shepherd King

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

The so-called ‘Bible of Raphael’ consists of a series of fifty-two paintings on the thirteen arches of the ceiling of the Loggia of the Apostolic (Vatican) Palace, a tall walkway open to the air on one side. It was decorated in fresco by a number of artists under the supervision of Raphael. The project was completed in 1519.

The painted narrative proceeds from the creation of the world as recounted in Genesis, to the life of Jesus. Every scriptural theme is represented in four paintings, each framed by false architecture and inserted into a large painted illusionistic structure showing the sky through columns.

The image of David’s anointing by Samuel is the first of four scenes from the life of David. The remaining paintings show David slaying Goliath; David seeing Bathsheba; and the triumph of David, who is shown in a chariot returning victorious from war, accompanied by captives.

The anointing scene takes place within an architectural structure rendered in realistic linear perspective. Through an open window we see trees and a vague landscape in the distance. In the centre, under the window, is a table with a cruse for oil. In front of it, and framing our view of it, stand Samuel and David. Samuel extends his arm to pour oil from a horn onto David’s bowed head; the young and handsome David, holding his shepherd’s crook, inclines in a graceful pose, with one leg bent. The other figures, all dressed in ‘classical’ attire, are equally distributed in a balanced composition. On the left, four of David’s brothers prepare a lamb for sacrifice. On the right stands Jesse with three more brothers.

Both the setting and the figures are rendered with Renaissance three-dimensional naturalism, creating visual plausibility. At the same time, the figures are idealized (one can see the influence of Michelangelo) and are artfully arranged.

The series as a whole presents the Scriptures as sacred history, culminating in Christ. The anointing of David evokes not only the idea of God’s elected king, but also that of shepherd; the sacrifice presages Christ as the sacrificial lamb, anticipating the final painting of the entire series, the Last Supper.

References

Davos, Nicole. 2008, The Loggia of Raphael: a Vatican Art Treasure (New York: Abbeville Press)

Magister, Sandro. 2009. ‘The Loggia Is Still Closed, but Raphael's Bible Is Now Open to the Public, 26 June 2009’, www.chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it, [accessed 15 October 2019]

Unknown Byzantine artist

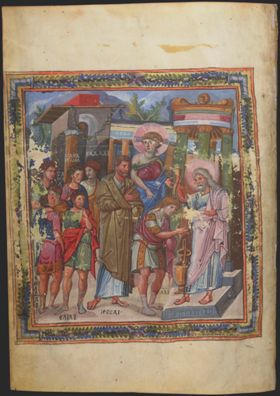

The Anointing of David, from the Paris Psalter, 10th century, Illumination on parchment, 370 x 265 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; Grec 139, fol. 3v, Bibliothèque nationale de France ark:/12148/btv1b10532634z

Sacred Rule

Commentary by Richard Viladesau

The Paris Psalter was probably commissioned by Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (reigned 945–59 CE). Its fourteen illuminations in tempera and gold leaf stress the sacred character of kingly rule. Eight depict David: one as the ideal priest/king; the rest showing him composing the psalms, defending his flock, anointed by Samuel, slaying Goliath, acclaimed by the populace, crowned as king, and repentant after Nathan’s reproach.

The illuminations’ colouring and technique imitate the classical style of fifth- and sixth-century painting. Like ancient pagan art, they include personifications of virtues and of nature. As we see clearly in the illustration of the anointing of David, multiple perspectives are deployed, including the inverse perspective associated with many Byzantine icons.

The size of figures indicates importance. Thus David’s seven brothers are shown on a smaller scale than David, although they are on the same plane. Their father Jesse is the largest figure. Samuel is shown standing on the steps of a columned building and pouring oil on the inclined head of David. Jesse and Samuel are dressed in classical togas over tunics with stripes (claves). David is dressed in a short tunic with gold stripes, and a short purple cloak draped over one shoulder—indications of his royal status. A symbolic female figure labelled ‘gentleness’ or ‘humility’ (praotēs), hanging in the air behind Jesse, points to the bowing David. Both Samuel and the personification have haloes behind their heads—a sign not of sanctity, but of importance.

The illustrations as a whole are a kind of imperial encomium. David is presented as God’s elected ruler: a type not only of Christ, but also of the Byzantine emperor. St Paul wrote that all authority is from God (Romans 13:1), and 1 Peter (2:17) enjoins Christians to honour the king. Church historian Eusebius wrote that God created the Roman empire. Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis affirmed that ‘God has sent the emperor to earth as living law’ (Novellae Constitutiones 105.2.4). This is reaffirmed by the Basilika of 888.

In seeing themselves in the image of God’s anointed—David and his descendant, Jesus—the Byzantine emperors reinforced their claim to rule on God’s behalf.

References

Dipippo, Gregory. 2017. “The Paris Psalter, 4 February 2017”, www.newliturgicalmovement.org [accessed 16 October 2019]

Unknown artist :

Samuel Anoints David, wall painting from the Dura-Europos Synagogue, 3rd century , Wall painting

Raphael :

David is Anointed by Samuel, c.1519 , Fresco

Unknown Byzantine artist :

The Anointing of David, from the Paris Psalter, 10th century , Illumination on parchment

Anointing of a Prototype

Comparative commentary by Richard Viladesau

King David was a central figure in Jewish consciousness: he was anointed by God’s hand through Samuel, as the Dura Europos painting illustrates; and he was the founder of a dynasty that would in the future produce an ideal anointed one, mashiach, the Messiah. Christians asserted that God’s action and promise had been fulfilled in Jesus, whom they called ‘Christ’, the Greek translation of ‘anointed’. Hence for them David’s anointing was typological: an Old Testament prefiguration of a later perfect fulfilment.

Our three artistic examples present the same scene, but with different styles and emphases. Common to all is the notion of anointing as a sign of election by God. In the Greek and Middle Eastern world anointing with oil (sometimes perfumed) had many contexts: anointing for athletics or for war; for healing; for enjoyment. It was a symbol of gladness (see Psalm 23:5; 45:7) and strength; it was a sign of hospitality (see Luke 7:46). It was also used in religious rituals of the consecration of kings and of priests. Moreover, the idea of anointing was used metaphorically for the reception of God’s spirit by the prophets (Isaiah 61:1). Hence Jesus applies the notion to himself (Luke 4:16–21) and Christians associated his anointing with his baptism (Matthew 3:16–17). In the same way, St Paul speaks of all Christians as anointed by the Spirit (2 Corinthians 1:21–22).

Given these many wide-ranging meanings, we can understand the importance of the anointing of David by God’s representative, Samuel. In the Dura wall painting, this scene stands among other instances of God’s action in history for God’s people, Israel: Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, the story of Moses and the Exodus, the vision of Ezekiel, the capture of the ark of the covenant, etc. The figures are stylized and formal, in the then-current Greco-Roman fashion; the painting is possibly modelled on illuminations of the Septuagint. It is significant that God’s election is presented uniquely in the anointing by Samuel, although the Scriptures mention two further anointings of David as King—over Judah (2 Samuel 2:4) and over all of Israel (2 Samuel 5:3).

The Paris Psalter illustrations emphasize the continuity of God’s action into the contemporary situation, through the divinely appointed Byzantine emperor. What was true when the original narrative was written down is true again here: Scripture lends itself to the legitimation of political authority. The Psalter illustrations complement Samuel’s anointing with pictures of David’s later royal accession. In one painting he is lifted by soldiers on a shield—a part of the Byzantine coronation ceremony—as a female figure floating in the air holds a crown over his head. In another, he is flanked by personifications of Wisdom and Prophecy; he wears a chlamys in the Byzantine style, like that of Justinian in the famous mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna; he carries a book, and gives a blessing in the sacerdotal manner, with his fingers arranged to form the Greek letters ICXC, the abbreviation of ‘Jesus Christ’. Above his head flies the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove—an allusion to Jesus’s ‘anointing’ by God at his baptism. The style of the Psalter illuminations is symbolic realism, in which the narrative takes precedence over visual coherence. The inclusion of labels within the paintings reinforces this emphasis.

The painting by Raphael also places the anointing in the context of the whole of sacred history and of major moments in David’s life. The emphasis here is on how the entirety of that sacred history, as recorded in the Old Testament, leads to fulfilment in Jesus. Jesus was thought to be of the ‘house of David’ by descent; he was also ‘son of David’ by virtue of his anointing by God. He is the Messianic king in a transferred sense: his kingdom is ‘not of this world’ (John 18:36); he reigns from the cross (Mark 15:2); he is ‘enthroned’ by his resurrection (Ephesians 1:19–23; Hebrews 1:5; Romans 1:4). Raphael’s inclusion of the sacrifice of a lamb in the anointing scene points forward to Jesus’s sacrifice, symbolically present in the final painting of the series, the Last Supper.

Raphael’s painting exemplifies a radical shift in art. Christian religious art prior to the Renaissance was above all symbolic and spiritual. It was meant to communicate knowledge and induce a sense of the spiritual presence of what it represented. Renaissance art reintroduced the classical idea of ‘imitation of nature’ (Seneca, Letter 65). Painting communicates what the eye can see, while striving for beauty. The anointing of David conveys sacredness through dramatic narrative, elegance of form, and context.

References

Babylonian Talmud, Horayot 11b; 12a; Jerusalem Talmud, Horayot 3.4, 47c

Belting, Hans. 1994. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Viladesau, Richard. 2009. ‘Art: Anointing’, in The Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception, ed. by Constance M. Furey et al (Berlin: De Gruyter)

Commentaries by Richard Viladesau