1 Samuel 16:14–23

David Plays the Harp for Saul

Rembrandt van Rijn

Saul and David, c.1651–54 and c.1655–58, Oil on canvas, 130 x 164.5 cm, The Mauritshuis, The Hague; inv. 621, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Oedipal Blindness

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Rembrandt van Rijn’s Protestant environment and Jewish neighbours are known to have enhanced his general interest in Old Testament scenes, but the exhilarating, almost oedipal drama dominating much of the books of Samuel—the fraught relationship between King Saul and his successor David—must have been particularly inspiring for the painter’s artistic temperament, drawn to darkness both literally and figuratively. The dramatic moments of that plot are only anticipated in the episode represented here—the very first encounter between the two men, narrated right after David’s clandestine anointing—but Rembrandt already sets the supposedly calm episode in a sombre, tense atmosphere. Only the two protagonists are represented, with the paradoxical combination—typical to Rembrandt—of quasi-monochrome dimness and ‘orientalist’ splendour.

David is completely dominated by the older king in terms of size, position, and lighting, but it is his excellence in music-making that saves the day. Mieke Bal (2006: 355–57) connects the psychoanalytic aspects of the narrative to an emphasis, frequent in the art of painting (and in particular in the work of seventeenth-century artists such as Caravaggio and Velázquez), on the ambitions and deficiencies of seeing. Indeed, the painting is an almost exact contemporary of Velázquez’s famously self-reflective Las Meninas (Museo del Prado, Madrid).

Rembrandt’s Saul and David is made still more complex by the dominant presence of sight’s rival sense: hearing. In a dark, visually impoverished environment, musical sounds could gain an enhanced medical and moral agency. Saul covers one of his eyes with what seems to be a curtain, becoming a cyclopean figure staring at the painting’s hypothetical spectators, whereas David’s gaze is vacant, his thoughts lost in the music he is making. While Saul is curled up as if protecting himself from the predicaments of his political life, the young musician emanates soundwaves reaching every corner of the depicted space. Saul seems conscious and wary of that invisible command and, while the Bible insists on his love for David at that moment, clearly senses how destabilizing to him such a power could become.

References

Bal, Mieke. 2006 [1991]. Reading Rembrandt: Beyond the Word-Image Opposition (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press)

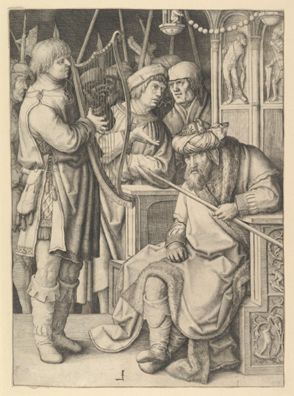

Lucas van Leyden

David Playing the Harp Before Saul, c.1508, Engraving; first state, 254 x 184 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1918, 18.65.7, www.metmuseum.org

Grotesque Madness

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Northern early modern artists routinely chose a grotesque register for their sacred scenes, but not any episode of Christian iconography would be considered apt for that treatment. While The Mocking of Christ or The Temptation of Saint Anthony were habitual occasions for outlandish grimaces and physical deformities of all kinds, the solemn, even lyrical story of David musically assuaging King Saul’s bad mood hardly seems to call for such handling. And yet, Lucas van Leyden, an artist often described as a Northern Mannerist, gives his figures that unmistakable aesthetic, shunning ideal beauty for the sake of a more piquant, slightly ridiculous presentation of his subjects.

Saul, in particular, is far from noble-looking; by contrast with what the biblical text affirms, David’s music seems to have had no effect on the ‘evil spirit from God’ that torments him (1 Samuel 16:14). Understandably perhaps: David’s perfunctory playing and stiff posture hardly appear inspiring. The king’s grumpiness—or otherwise more serious mental illness, such as the Dutch biographer Karel van Mander detected in Saul’s face here as early as 1604 (Wagini 2017)—is compounded by his (involuntary?) gesture of pointing his spear towards David, an obvious anticipation of the later episode (1 Samuel 18:10–13) in which Saul will attack the musician with that same weapon. Indeed, the two biblical passages are often conflated in early modern images.

The medium of engraving, with its reproducibility and thus a far broader audience than painting, lends itself to a lighter tone, or at least to the inclusion of anecdotal detail ensuring the immediate curiosity of potential buyers. Inherent to such a variety of details is the presence of bystanders, densely crowding the background of the scene, and the vivacious, comically graceful sculptural reliefs adorning the king’s throne. At least one of the latter decorations—possibly Cain assassinating his brother Abel—presents darker overtones hinting at Saul’s madness, as it depicts a violent attack.

References

Wagini, Susanne. 2017. Lucas van Leyden: Meister der Druckgraphik (Munich: Staatliche graphische Sammlung München

Mattia Preti

David Playing the Harp Before Saul, c.1670, Oil on canvas, 208.5 x 301.8 cm, Private Collection; With The Matthiesen Gallery 1986; Photo © Matthiesen Ltd.

The Biblical Orpheus

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Mattia Preti, who was active in the most important hubs of Caravaggism in Southern Europe—Rome, Naples, and Malta—presents here a belated version of some of the typical characteristics of that style. His depiction of the first encounter between Saul and David is vigorous and dynamic, far from the lethargic melancholy suggested by other artists. In this sense, it can be deemed typically Baroque; it insists on the ephemeral instant in a composition ostensibly frozen in time. Witnesses of every gender, age, and race are petrified by the musical charisma of the future psalmist. Preti’s typical brilliant white light enhances the drama: the cloudy sky seems to be clearing up just like Saul’s melancholia.

For the biblical episode, Preti borrows elements from an eclectic array of sources, both mythological and mundane. The figure of David attracting a motley group of people to his magical music-making is reminiscent of Orpheus’s magnetic prowess—pacifying the entire natural world with his lyre. Closer yet to his habitual artistic references, Preti here pursues the development of tavern and concert scenes to which Caravaggist circles earlier in the century repeatedly contributed.

Paradoxically, in this group of humans all ravished and hypnotized by the talented harpist, the least affected seems to be Saul himself. Dominating the diagonal composition but still shrouded by shadows and thus contrasted with the brightly-lit David, the older king is shown to belong to Israel’s past, on his way to oblivion. Perhaps recalling what was suffered by the recipients of certain mental health treatments in Preti’s day, Saul is here paying the price of a debilitating apathy for the tranquillisation of his ‘evil spirit’ (1 Samuel 16:14). The solace brought to him by David is as ephemeral as the instant depicted here; soon enough, the new king will make him jealous and frustrated; worse still, David will deprive him of his dynastic posterity.

Rembrandt van Rijn :

Saul and David, c.1651–54 and c.1655–58 , Oil on canvas

Lucas van Leyden :

David Playing the Harp Before Saul, c.1508 , Engraving; first state

Mattia Preti :

David Playing the Harp Before Saul, c.1670 , Oil on canvas

The Power of Music

Comparative commentary by Itay Sapir

1 Samuel 16:14–23 presents two main themes, and any artist depicting this narrative must take both into account, though the respective dosage can vary. We are witnessing here the inaugurating scene of a saga: it is the first time future rivals David and Saul meet and thus the scene anticipates their complex love-hate relationship. But the scene is also an instance of a prominent intellectual topos in early modern culture: the power of music as purveyor of tranquillity and mental health.

One could sum up the difference between the three representations of the scene discussed here by saying that in each one of them the artist chose to follow the aesthetics of a different early modern theatrical genre. Lucas van Leyden—surprisingly, perhaps, given the story’s dark themes—designed a comic scene, more Molière (avant la lettre) than Shakespeare. It represents the protagonists as, respectively, an excessive, instable, irrational but powerful older man and a young, seemingly clumsy, but secretly cunning and ambitious younger heir.

Rembrandt van Rijn opted for his typical mode of dark tragedy (King Lear inevitably comes to mind), emphasizing aspects of loneliness, despair, failure to see, and dynastic dead end.

Mattia Preti, for his part, put Saul and David at the centre of a silent opera. The new genre of musical theatre was born in Italy at the beginning of Preti’s own century. It was obsessed, in the first few decades of its existence, with the quintessential classical myth about the power of music: the story of Orpheus hypnotizing all nature to placidity and softening even the hearts of the rulers of Hades through his mastery of the lyre. David Playing the Harp before Saul could be an instrumental intermezzo of such a work, proof of the invincibility of music and of its capability to attract, unite, and pacify all living creatures. David, allegedly the future author of the psalms and thus himself not only an improvisatory musician but also the author of divinity-pleasing verse, is thus the Orpheus of Israel, aptly celebrated in an operatic mode, in a spectacle of music, poetry, and extravagant visual effects.

Beyond this difference of genre, rhetorical mode, and mood, the three representations mostly converge in the specific depiction of both the nascent relationship between Saul and David and the effectivity of music ‘pour passer la mélancolie’ (‘to put melancholy behind you’, the explicit ambition of Johann Jacob Froberger’s Suite no. 30, c.1650, as stated in the title of its first movement).

In the Old Testament, Saul’s servants promise him that once someone ‘skilful in playing the lyre’ entertains him, he will ‘be well’ (v.16). In view of the subsequent episode in which Saul attacks David while playing, anticipated by the presence of a spear in the king’s hand in all three images, the position of the artists on the issue seems more cautious. Lucas is ironic about the possibility that Saul would be durably assuaged by David’s playing; Rembrandt’s Saul is still immersed in his bad mood and so, in spite of the evident marvelling of all the bystanders, is Preti’s royal figure. The visual splendour of Preti’s work might suggest that where music’s power is significant but limited and ephemeral, painting could more reliably charm its spectators and give them satisfaction. The two artists from Leiden, on the other hand, do not hint at such an advantage for their own medium, as Rembrandt’s painting is austere and hardly soothing and Lucas’s engraving excites nervous laughter more than it appeases.

All three artists emphasize the complexity and the ambiguity of the future relationship between the older king and the man just anointed to take his place. In spite of the laudatory description of David by one of Saul’s courtiers, and the immediate liking the king conceived for him, none of the artworks takes this report at face value. All describe a tension not yet literally present in our biblical passage but dominating the following chapters. These chapters will recount the uncomfortable coexistence of the two kings—one fallen from grace, the other destined to fame and glory (though not unambiguous either). In fact, the two themes are closely linked: Saul’s anxiety might indeed have been soothed by music, but (ironically) it was precisely the person brought to try to lull him into tranquillity who would justify his fears. Our three artists, knowing what the books of Samuel will narrate next, are fully aware of the hopelessness of this endeavour, or at least of its necessarily short-lived success.

Commentaries by Itay Sapir