Psalm 23

The Lord is My Shepherd

Unknown French artist

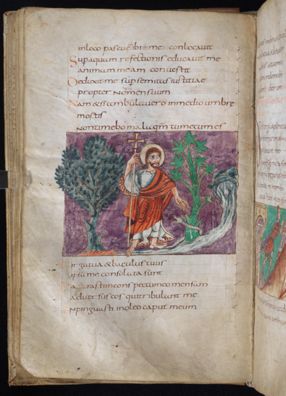

Psalm 23, from the Stuttgarter Psalter, First half of the 9th century, Illuminated manuscript, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart; Cod. bibl. fol. 23, f. 28v

The Death-Defying Shepherd

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

This ninth-century Carolingian illumination of Psalm 23 is found in the Stuttgart Psalter. The manuscript uses 316 illuminations to accompany the Psalter. In contrast to the almost contemporary Utrecht Psalter, which is characterized by a concern to illustrate every detail of the ‘word-pictures’ in the Psalms, the Stuttgart Psalter takes a more pared down approach.

Accordingly, in this illumination made to accompany Psalm 23, one theme is prioritized, that of the protective ‘Shepherd / Lord’ of Psalm 23:1–4. In the centre, in the heavy, brightly-coloured style that is characteristic of the Stuttgart, stands the Shepherd, nimbed with a halo and holding a staff or ferula (Psalm 23:4). The Psalmist himself, the speaker of the Psalm, is noticeably absent. The ‘still waters’ of Psalm 23:2 are represented by the stream on whose banks the ‘Shepherd’ stands, and the green pastures (also of Psalm 23:2) by the two trees to his right and left (painted in markedly different styles). The ‘evil’ referenced in verse 4 is here suggested by the snake wrapped around the base of the tree to the ‘Shepherd’s’ right, which he is calmly subduing with his extended right hand. The combination of the tree (which recalls the tree of knowledge of Genesis 2:17); the serpent (which is viewed within Christian theology as the bringer of death to humankind, see Genesis 3); and the haloed Shepherd, a figure who, in the New Testament, is often linked with Christ, implies that in this illumination, Psalm 23 is being interpreted ‘typologically’ (when the Old Testament is read through the prism of the New).

Bearing the cross as the Shepherd in the Psalm bears his staff, Christ opens the way to salvation, and leads his people along it.

References

Hill, Robert C (Trans.). 2000. Theodoret of Cyrus: Commentary on the Psalms, 1-72, The Fathers of the Church (Washington, DC: CUA Press)

Roger Fenton

Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855, Salted paper print, 276 x 349 mm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 84.XM.504.23, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

The Valley of Death

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

Roger Fenton’s photograph of the Crimean ‘valley of death’ (the ravine that ran between the British and Russian camps during the Crimean war) represents a key moment within the reception history of Psalm 23. It is both a reinterpretation of the Psalm for the age of modern warfare, and testament to the Psalm’s ubiquity within British culture. The British familiarity with the Psalm was largely due to the multiple woodcut versions of Pilgrim’s Progress that had flooded the market since the late seventeenth century and which all featured an image of Christian in the ‘valley of the shadow of death’.

Fenton, one of the first war photographers, had been commissioned to take photos of the Crimean War. Because Victorian sensibilities could not tolerate graphic photographs, Fenton focused on the ‘landscape of aftermath’ (Grant 2005). Thus this image, exhibited by Fenton on his return from the Crimea in 1855, depicts the aftermath of a battle in the area referred to by the troops as ‘the valley of death’ (see Psalm 23:4), a location that was also immortalized by Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854).

Fenton’s landscape is devoid of human, animal, or indeed any living presence. Instead, the barren hills and the snaking road are covered in cannonballs and other debris, a grim reminder of the human loss that the landscape repeatedly bore witness to throughout the war. The connection of the landscape in this photograph with Psalm 23 by the authors of the 1855 exhibition catalogue (who appended the title to the image) brings new meaning to the notion of the ‘valley of the shadow of death’ evoked in 23:4. Here in the photograph, the ‘valley of the shadow of death’ from which the Lord is said to provide protection is a literal valley scattered with the debris of modern warfare, in which many experienced great ‘darkness’. Whether Fenton’s photograph suggests a continuation of that divine protection, is entirely ambiguous.

References

Grant, Simon 2005: ‘A Terrible Beauty’, Tate Etc, 5, available at https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-5-autumn-2005/terrible-beauty

Unknown artist

The Parma Psalter, 13th century, Illuminated manuscript, Palatina Library, Parma; Ms. Parm. 1870, Cod. De Rossi 510, fol. 29a, Courtesy of Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Tourism

By Still Waters

Commentary by Natasha O’Hear

The Parma Psalter is a rare example of a Jewish illuminated Psalter, produced in Italy during a time of Jewish persecution. Puzzlingly, this Psalter seems alone in having escaped the prohibition on human representation that applied to (extant) contemporaneous Ashkanazi manuscripts (see Beit-Arie, Silver & Metzger 1996: 103–07). One artist is thought to have produced all its 102 illuminations. Text and image are interwoven with each other, resulting in intricate geometric designs.

Deep knowledge of the Hebrew text of the Psalms has resulted in an iconographic schema which bears little relation to the established Christian iconography of the Psalms, itself influenced by the Vulgate translation of Psalm 23:4. In the Vulgate translation the Hebrew word salmawet (meaning deep shadow or death shadow; BDB 6757) became (via the Greek Septuagint’s skias thanatou) ‘the shadow of death’. The single Hebrew word became two words; death became a freestanding noun rather than a intensifying qualifier of ‘shadow’. This reinforced a Christian interpretation that looked to redemption in another world beyond this mortal one.

Within the Jewish tradition, by contrast, instead of conveying a promise of eschatological deliverance (from the ‘valley of the shadow of death’), the Psalm is seen to celebrate God’s constant presence in this life, even through exile and other negative experiences (see Gillingham 2018: 144–47).

This more hopeful, ‘this-worldly’ Jewish interpretation of the Psalm is reflected in the Parma artist’s decision to focus on the joyful opening of the Psalm, which emphasizes God’s loving care for his people on earth. The Psalmist, a symbol of ‘God’s people’, is thus portrayed as a human figure with a dog’s head, wearing a brown hat with a distinctive rim, and sitting on a grassy knoll next to a river. The mixing of human and animal bodies is common in the Parma psalter (although unusual elsewhere) and may be a visual nod to the notion, which runs through the Psalms, that every creature should participate in the universal praise of God’s glory (Beit-Arie, Silver & Metzger 1996: 103).

Accordingly, this hybrid Psalmist figure raises his hands in supplication, whilst a brightly-coloured bird flies above him. He conveys the spirit of the original Jewish exile, encouraging his viewers to stay faithful and hopeful during their own period of persecution.

References

Beit-Arie, Malachi, Emanuel Silver, and Thérèse Metzger. 1996: The Parma Psalter: A Thirteenth-century Illuminated Hebrew Book of Psalms with a Commentary by Abraham Ibn Ezra (London: Facsimile Editions)

Gillingham, Susan. 2018: Psalms Through the Centuries: Volume 2 (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell)

Unknown French artist :

Psalm 23, from the Stuttgarter Psalter, First half of the 9th century , Illuminated manuscript

Roger Fenton :

Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1855 , Salted paper print

Unknown artist :

The Parma Psalter, 13th century , Illuminated manuscript

Pastoral Idyll or Vale of Shadows?

Comparative commentary by Natasha O’Hear

In many parts of the Christian tradition Psalm 23 has become closely associated with funeral services—it was formally included in the Church of England’s burial liturgy in 1928, for example. But the history of this well-loved Psalm within both Jewish and Christian traditions is more complex and varied than this association alone.

The wealth of different visual approaches that have been taken to its interpretation are in part a consequence of the non-narrative quality of biblical psalms. The Psalms tend to reflect and provoke human emotion rather than to record events or set out narratives. The artworks made in response to them, rather than being literal representations of the text, tend to be ‘word pictures’ generated by specific words or phrases. Thus the varied visual history of Psalm 23 is, to an extent, the result of artists responding to or prioritizing different sections of the Psalm.

Most artworks inspired by Psalm 23 (or commissioned to illuminate it) prioritize either the pastoral side of the Psalm (as in the case of the Parma illumination) or the ‘valley of the shadow of death’ of Psalm 23:4 and its attendant imagery (as in the Stuttgart illumination). The latter strand became progressively more dominant, thanks in part to the multiple illustrated versions of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (the most translated book after the Bible), which includes a section in which Christian, the ‘everyman pilgrim’, has to traverse the ‘valley of the shadow of death’ (Collé-Bak 2010: 224). By the time Roger Fenton exhibited his photograph of the Crimean ‘valley of death’ in 1855, Psalm 23:4 was so well embedded in the British cultural landscape that the title The Valley of the Shadow of Death could be appended to the image by the authors of the exhibition catalogue without further explanation (Groth 2002: 553).

How can the combination of these three contrasting artworks enrich our understanding of the Psalm? It is important to reiterate that for most of its Jewish and some of its Christian history Psalm 23 was understood as a pastoral Psalm (akin to Psalms 16 and 22), which emphasized God’s providential care for the world in this life and the resultant need for confidence and trust in him. The Parma illumination, which reflects Psalm 23’s imagery of ‘green pastures’, ‘still waters’, and restoration (vv.2–3) orients the viewer towards just such a pastoral interpretation (and the Utrecht Psalter, which is contemporary with the Stuttgart Psalter, is also celebratory of the abundance of divine blessing). The ‘deep shadow’ of 23:4 does not carry the connotations of the valley of death that the Latinate Christian tradition later attached to it. In the Parma illumination there is an absence of eschatological references and the mention of ‘evil’ has been passed over in favour of a more positive, present-orientated depiction of this unusual Psalmist delighting in the natural world.

The Stuttgart illumination, by contrast, while using the Psalm’s pastoral imagery as a backdrop, clearly prioritizes the imagery found in 23:4 of the Lord (here conceived of as Jesus) offering protection from evil and death in both a present and future capacity. This is one of the first images to emphasize the Psalm’s darker side through the prism of a typological reading. In promoting Psalm 23:4 in this way, over and above other aspects of the text, the Stuttgart illumination anticipates a long strand of engagement with this section of the Psalm. While in verse 4 itself the Psalmist seems quite clear that despite his brush with ‘death’, evil need not be feared, in some later strands of the visual, musical, and filmic reception in particular, the motif of the ‘valley of death’ becomes connected with hopelessness and religious despair (Roncace n.d.).

Roger Fenton’s sepia-toned image, as well as being one of the first photographic representations of the aftermath of modern warfare, pre-empts this current. The Charge of the Light Brigade was an ignominious military failure with devastating casualties. The photograph strikes a very different note from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poetic tribute to their heroism.

Unlike the other two works explored in this exhibition, which are physically anchored within illuminated Psalters and thus within the text of Psalm 23, Fenton’s photograph was not conceived as a response to Psalm 23. However, the juxtaposition of the eerie, almost post-apocalyptic Crimean landscape, with the photograph’s title (The Valley of the Shadow of Death) prefigures some of the later, bleaker, cultural engagements with the Psalm, such as Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider (1985) or Coolio’s Gangsta’s Paradise (1995). Fenton’s photograph lacks any sense of the religious certainty that pervades the rest of the Psalm, as well as the other images in this exhibition. It is therefore a partial yet deeply unsettling visualization that invites us to see Psalm 23 in an alternative light.

References

Beit-Arie, Malachi, Emanuel Silver, and Thérèse Metzger. 1996: The Parma Psalter: A Thirteenth-century Illuminated Hebrew Book of Psalms with a Commentary by Abraham Ibn Ezra (London: Facsimile Editions)

Collé-Bak, Nathalie. 2007: ‘The Role of Illustrations in the Reception of The Pilgrim’s Progress’, in Reception, Appropriation, Recollection: Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. by W. Owens and Stuart Sims (Oxford: Peter Lang), pp. 81–97

Gillingham, Susan. 2018: Psalms Through the Centuries: Volume 2 (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell)

Grant, Simon 2005: ‘A Terrible Beauty’, Tate Etc, 5, available at https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-5-autumn-2005/terrible-beauty

Groth, Helen. 2002. ‘Technological mediations and the public sphere: Roger Fenton’s Crimea exhibition and “The Charge of the Light Brigade”’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 30.2: 553–70

Roncace, Mark. n.d. ‘Psalm 23 as Cultural Icon’, www.bibleodyssey.org, available at www.bibleodyssey.org:443/en/passages/related-articles/psalm-23-as-cultural-icon

Commentaries by Natasha O’Hear