Hebrews 11

A Question of Faith

Colin McCahon

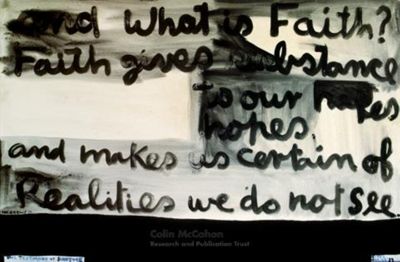

The testimony of scripture no. 1, 1979, Synthetic polymer paint on paper, 730 x 1100 mm, Private Collection; © Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

To Our Hopes

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

‘What is faith?’ A compelling question scrawled across the top of a paper sheet. The painted text continues with Hebrews 11:1—‘Faith gives substance / to our hopes / hopes / and makes us certain of / Realities we do not see’—set out as a Tau Cross. ‘To our hopes’ forms the vertical of the cross and ‘hopes’ is twice repeated. The reinscribed word is perhaps an echo of the tablets of the Law that were broken and reinscribed; hope as future renewal and restoration. A companion work entitled The testimony of scripture no. 2 makes further use of the Tau Cross; as a load-bearing structure supporting a text (Hebrews 11:3) which speaks of the invisible made visible.

The question posed is that which Hebrews 11 seeks to answer. It is a question that preoccupied Colin McCahon throughout his career, to the extent that an earlier work entitled A question of faith (1970) provided the title for a retrospective in 2002.

McCahon began making A question of faith after he ‘got onto reading the New English Bible’ and re-read his favourite passages. Reflecting on this period for his 1972 survey exhibition, he wrote:

It hit me, BANG! At where I was: questions and answers, faith so simple and beautiful and doubts still pushing to somewhere else. (McCahon 1972: 36)

Nine years later, faith and doubt, questions and answers, were still a preoccupation that enthralled him. In The testimony of scripture no. 1 the Tau Cross is given substance as a narrow vertical connecting the wider horizontal bands of text at top and bottom, as though a link between heaven and earth. An answer to the ‘question of faith’ is suggested by showing the cross as connecting the human and divine; a reality that we must work hard to discern but which gives substance to our hope for union with God.

References

McCahon, Colin. 1972. Colin McCahon: A Survey Exhibition (Auckland City Art Gallery)

Colin McCahon

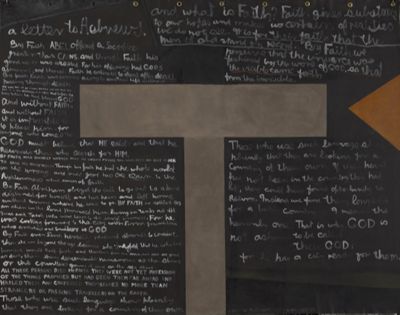

A Letter to Hebrews, 1979, Synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 187 x 240 cm, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington; Gift of anonymous donors with assistance from the Willi Fels Memorial Trust, 1981, 1984-0004-1, © Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust; Photo: Museum of Te Papa Tongarewa (1981-0004-1)

Yet To Come

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

Colin McCahon writes in white text on a black ground. Black is for earth, the ground from which new things emerge and potentiality is actualized (Brown n.d.: 5). The white text—though McCahon’s own (human) writing—points to the creative (divine) word which calls life itself into being. Fashioned by the Word of God, the visible comes forth from the invisible and it is by faith that we perceive it. The text, at points, is clear and elsewhere is faded. It is emergent and—as faith not certainty—encompasses doubt.

McCahon set Hebrews 11:1–16 around a central Tau Cross and alongside a golden triangle. He began with verses 4–15 which recount stories of faith, then returned to the beginning with verses 1–3, including the question ‘What is faith?’, before ending with verses 15–16, which look towards a promised land yet to come.

In Christian tradition, the Tau Cross was associated with the Passover, being linked to the symbol made in blood on the door lintels of the Israelites in Egypt when the angel of death passed over (Exodus 12:7). A symbolism that can be read as both Christian and pre-Christian is appropriate for a letter which reveals Christ as fulfilment of the Hebrew Scriptures. Seeing the Tau Cross as a sign of Christ suggests that all McCahon’s ‘religious pictures are typography; or maps with Christ as their hidden incarnated key’ (Leonard n.d.).

Gordon Brown, a close friend and biographer of McCahon, suggested that the golden triangle ‘thrusting in from the edge’ toward the cross represents ‘a future Trinity’ (2010: 172). The revelation of the Trinity, which will happen long after the recorded histories of the ancient Israelites, is anticipated here amidst Hebrews’s roll call of the Old Testament faithful. The Trinity, present in splendour, points to the cross, the symbol both of Christ with us and the pathway to the ‘better country’ (v.16) up ahead.

References

Brown, Gordon H. 2010. Towards a Promised Land: On the Life and Art of Colin McCahon (Auckland University Press)

Brown, Judith. n.d. ‘‘And Darkness Came over the Whole Land’: Some thoughts on Colin McCahon and the Colour Black’, unpublished article, www.academia.edu [accessed 14 April 2021]

Leonard, Robert. n.d. ‘Colin McCahon, Toi Toi Toi, Kassel and Auckland: Museum Fredericanium and Auckland Art Gallery, 1998’, www.robertleonard.org [accessed 14 April 2021]

Colin McCahon

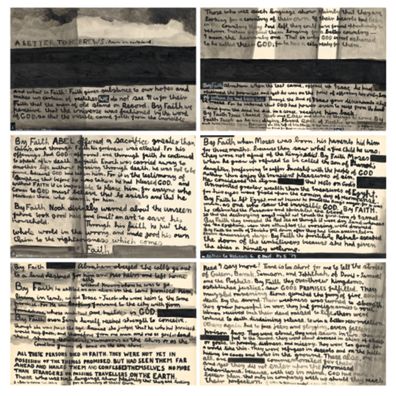

A Letter to Hebrews (Rain in Northland), 1979, Synthetic polymer paint on 6 sheets of paper, each sheet: 730 x 1102 mm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria in memory of the Reverend Stan Brown by the Reverend Ian Brown, Fellow, 1984, P6.a-f-1984, © Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

To Walk Past

Commentary by Jonathan Evens

This painting, composed of six sheets of paper, layers the whole of Hebrews 11 ‘across a brooding sky and sea in New Zealand’s Northland’ (Artwork labels 2019). The work offers ‘schematic evocations’ of landscape. Long black strips in the upper sections suggest a rain-swept terrain, viewed from a distance across an expanse of sea filling the lower three quarters. From the sky ‘muted shafts of sunlight’ shine through ‘washed-out cloud formations and slanted sheets of rain’ (Smythe 2019). In the lower sections, the text shimmers like ripples on the Northland waters. In the top right, the reflected fall of light below the narrower strip of land forms one of Colin McCahon’s trademark Tau crosses.

In evoking a challenging landscape through which to journey, Rain in Northland seems symbolically charged with the ‘travels and travails of Christ’s Hebrew forebears’ in their search for the promised land, as Hebrews 11 documents it.

McCahon’s artistic vision was grounded in landscape. He became aware of his ‘own particular God’ driving over the hills from the Taieri Mouth in southern New Zealand to the Taieri Plain, seeing a splendour and beauty ‘belonging to the land and not yet to its people’. He wrote that his work as a whole had ‘largely been to communicate this vision and to invent the way to see it’ (McCahon 1988: 76).

Four months spent in America during 1958 marked a watershed in that artistic outlook. Subsequently, he worked on a monumental scale creating ‘pictures for people to walk past’ (Smith 2001: 2). These include his Northland Panels and other series exploring doubt and faith. By combining minimal marks and dense text, Rain in Northland makes it hard for us to distance ourselves from the work, suggesting that this combination of faith and doubt, as seen in sun and rain, wants to immerse us in the picture so we walk the landscape of faith with the Hebrew forebears of Christ.

References

‘Colin McCahon Letters and Numbers: Artwork Labels’. 2019. National Gallery of Victoria, available at https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Colin-McCahon-Labels.pdf [accessed 14 April 2021]

McCahon, Colin. 1988. ‘Artist’s Statement’, in Colin McCahon: Gates and Journeys, (Auckland City Art Gallery)

Smith, Jason. 2001. ‘Essay: Colin McCahon’, in Colin McCahon: A Time for Messages (National Gallery of Victoria)

Smythe, Luke. 2019. ‘Review of Colin McCahon: Letter and Numbers at National Gallery of Victoria, 31 December 2019’, www.memoreview.net [accessed 14 April 2021]

Colin McCahon :

The testimony of scripture no. 1, 1979 , Synthetic polymer paint on paper

Colin McCahon :

A Letter to Hebrews, 1979 , Synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas

Colin McCahon :

A Letter to Hebrews (Rain in Northland), 1979 , Synthetic polymer paint on 6 sheets of paper

The Direction I’m Pointing In

Comparative commentary by Jonathan Evens

Colin McCahon stated that his ‘painting … tells you where I am at any given time, where I am living and the direction I am pointing in’ (McCahon 1972: 26). He also painted the words of New Zealand poet Peter Hooper (1919–91): ‘Poetry isn’t in my words, it’s in the direction I’m pointing’ (1969). Paintings and poems are compasses for a journey of ultimate significance. Hebrews 11 ‘recounts the travels and travails of Christ’s Hebrew forebears’ on a journey towards a promised land that has not yet been reached (Smythe 2019). The text suggests that to travel in this way is a definition of faith. Those commended for their faith react to things not yet seen and live as those looking ‘forward to the city that has foundations, whose architect and builder is God’ (Hebrews 11:10).

McCahon’s personal journey was bound up in the perception that, in the past, painters had made ‘signs and symbols for people to live by’ but now they make ‘things to hang on walls at exhibitions’ (McCahon 1972: 26). McCahon’s career was a journey of discovering what it meant to be a symbolic signwriter in the twentieth century.

That journey was inspired by youthful sights in Dunedin of a signwriter working on a shop window and a cross-shaped memorial to a parachutist on the North Otago hills (Bloem and Browne 2002: 160, 162). Then there was an encounter with Frank Tosswill, uncle of his friend the artist Toss Woollaston, whose blackboard signs lettered with religious texts and Christian symbols had an impact on McCahon’s thinking about art and faith.

McCahon introduced text into his religious paintings from 1947—his first sustained series in which religious imagery was translated into a contemporary style and put into New Zealand settings. In 1954, he produced the first paintings in which he used words to form the dominant motif—to become the image—often forming landscapes. In these ways McCahon became a symbolic signwriter and, as in his 1959 Elias works (not shown here), used this mature style to explore the deeply human concept of doubt.

He first used passages from Hebrews in Scrolls from 1969 but, in 1970, was specifically asked by a Wellington collector to consider the possibilities this book might hold for a painting. It was not until 1979 that he felt sufficiently confident in his understanding of Hebrews to explore its possibilities in the works included in this exhibition.

Walking past these works from 1979 onwards, we pass ‘landscapes’ of splendour, order, and peace; visible beauty belonging to the land and not yet to its people; logic and order revealing their invisible fashioning by their creator. These works, as we journey through them, register experiences of ‘directional travel’, both personal and corporate—McCahon’s own experiences, as well as those of the ancient Hebrews, as well as the Church’s over many centuries. These are journeys on which challenges, struggles, and doubts have been encountered, even as a ‘homeland’ (v.14) is glimpsed. Connecting these works is the Tau Cross, an image that Christian tradition sees as spanning both Testaments—Old and New—signalling events in the horizontal timeline of human history (Passover and Good Friday) that also make a vertical connection between heaven and earth. The Tau Cross becomes a pillar of light for guidance and direction.

The experience of those documented in Hebrews 11 was of the promised land always out of reach. McCahon suggests this lack of resolution within Rain in Northland. Luke Smythe, a particularly sensitive interpreter because he attends to the repetition of imagery within the different series, notes that the ‘hovering black rectangles that appear here and there amid the text are harder to interpret’:

They suggest editorial redactions, but since no words have been cut from the inscriptions, they are more likely to be gates, of the kind that McCahon had introduced to his painting in the 1960s. He intended these cryptic quadrilaterals to read as obstacles, blocking access to a state of salvation. For him, it was a question of faith as to whether they could ever be negotiated and the promised land attained. (Smythe 2019)

McCahon’s personal journey, involving both faith and doubt, mirrored the ‘travels and travails’ documented in Hebrews 11. Hebrews in turn enabled his understanding that to journey in this way is an expression of faith and to travel towards a promised land is an act of faith.

References

Bloem, Marja, and Martin Browne. 2002. Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith (Craig Potton Publishing and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam)

Hopper, Peter. 1969. ‘Poetry is for Peasants’, in Journey Towards an Elegy and Other Poems (Nag’s Head Press: Christchurch)

McCahon, Colin. 1972. Colin McCahon: A Survey Exhibition (Auckland City Art Gallery)

Smythe, Luke. 2019. ‘Review of Colin McCahon: Letter and Numbers at National Gallery of Victoria, 31 December 2019’, www.memoreview.net [accessed 14 April 2021]

Commentaries by Jonathan Evens