Hebrews 13:1–25

Seeking the City Which is to Come

Unknown Roman artist

Relief from the Arch of Titus Rome, Roman soldiers carrying the golden menorah and other spoils from the Temple of Jerusalem, c.81 CE, Stone; shapencolour / Alamy Stock Photo

An Alternative City

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

After the emperor Titus's (ruled, 79–81 CE) death and divinization, his brother Domitian (emperor, 81–96 CE) erected the Arch of Titus to commemorate Titus's apotheosis, to secure his own dynastic succession, and to acclaim himself the son of the divine Vespasian.

The arch stands on the Roman forum on the via sacra, the route taken by generals to celebrate Roman military triumphs and to divinize deceased rulers.

Together with his father Vespasian (emperor, 69–79 CE), Titus squashed a Jewish rebellion in Roman Palestine (66–73 CE) and destroyed the Temple. The south inner panel relief—originally painted—freeze-frames a moment of the triumphal procession that followed. Roman soldiers bear plunder from the Temple’s inner sanctum: trumpets, the menorah, shovels for removing ashes from burned altar offerings, and the table of the Showbread. Some carry placards that describe the plunder.

We do not know whether the audience of the Letter to Hebrews joined the crowds lining the streets of the procession, but they could hardly have escaped news of it. For them, the Triumph inscribed the trauma that accompanied every Roman conquest. The author of Hebrews refuses to avert his eyes. ‘Remember those who are in prison…; those who are being tortured’ (Hebrews 13:3). ‘Let us go to him [Jesus] outside the camp and bear the abuse he endured. For here we have no lasting city, but we are looking for the city which is to come’ (13:12–14 NRSV).

The procession will proceed to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus where the emperor will sacrifice to the city’s top god for granting the Romans another victory; prisoners will be executed or sold into slavery (thousands of them were building the Coliseum); the emperor will pay his army with plunder.

Subversively, the author says Rome’s capital is not the eternal city of its own propaganda; the real, enduring one is still on the way. Meantime, listeners are to go to the one who is ‘outside the camp’ and behold a different son of god—‘the exact imprint of God’s very being’ (Hebrews 1:3 NRSV) whose way is not one of murder, destruction, and plunder, but that of ‘mutual love’ (13:1).

Micah Bazant

Refugees are welcome here , 2015, Poster, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) Artist Council; ©️ Micah Bazant

Hosting Angels

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it. (Hebrews 13:2 NRSV)

Hebrews commands its audience to remember the imprisoned and tortured as though they themselves were in prison and suffering torture (v.3). At the end of 2020 there were 82.4 million forcibly displaced people, double the number in 2010; 24.6 million of them were refugees (6.7 million from Syria), many of them fleeing persecution and torture (UNHCR 2020).

In 2015, Jewish trans artist Micah Bazant worked with Jewish Voice for Peace to create these posters combating Islamophobia and anti-immigrant racism. In ‘Refugees Are Welcome Here’ (one of several similar images), the poster sets against a blue background a black and white image of a bearded man with deep worry lines, holding in his coat his little daughter with a head covering. The eyes of the man and child stare at the viewer in anticipation. Will we welcome them? If we do, we will not remain the same.

The word ‘angel’ is a cognate of the Greek word angellos which means messenger. What messages do such strangers bring when we welcome them? How do they teach us to see the world and ourselves? What conversations unfold when we talk with those who have suffered violence and deprivation? How does God address us through their testimony? To what future and commitments do they call us? As they make their memories present to us, we re-member—literally reassemble—and join in solidarity with them in their trauma.

Hebrews addressed an audience living at a time when persecution under Nero and suppression of the Jewish revolt in Roman Palestine were fresh memories or active events. Even as it exhorted listeners to hospitality, they hardly needed a reminder that they too were strangers to their surrounding civil order (13:14). Perhaps in welcoming one another they were being called upon to be messengers to one another of God’s presence with them; that whatever else might change amidst their collective fortunes, God’s promise to them would not, for ‘Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever’ (13:8 NRSV).

References

UNHCR. 2021. Global Trends in Forced Displacement 2020 (Copenhagen: UNHCR Statistics and Demographics Section)

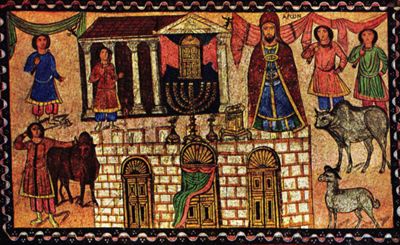

Unknown artist

Fragment from the Dura Europas synagogue, Completed 244 CE, Wall painting, National Museum of Damascus; CPA Media Pte Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Sacrifice Outside the Camp

Commentary by Harry O. Maier

In 1932 archaeologists discovered a third century CE synagogue at Dura-Europos, a Syrian settlement on the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire, whose interior was covered with colourful wall paintings depicting scenes from the Hebrew Bible. The surrounding images placed worshippers in the sacred time and space of Israel’s tradition. Steven Fine hypothesizes that Jewish preachers used the images as aids for homiletic exposition (Fine 2005: 181–82).

The western wall of the synagogue (facing Jerusalem) depicts Herod’s Temple. Aaron and the tabernacle are to its right; a menorah, altar, and incense burners are before him. Below are a bull and goat and the doors to the Temple. Assistants stand around the Temple; the one on the bottom left is leading a red heifer which Numbers 19:2 instructs Aaron to sacrifice outside the camp for purification. The bull, goat, and incense may also refer to atonement sacrifices which Leviticus 16 commands Aaron to offer. The mural is juxtaposed with scenes on the adjacent walls that include Elijah’s contest with the priests of Baal (1 Kings 18:20–40) and the destruction of a statue of the Philistine god Damon after Philistines stole the Ark of the Covenant and placed it in his temple (1 Samuel 5).

The synagogue images reveal a Jewish community preserving its sacred narratives in a world of innumerable gods and rituals. Yet they do so in a hybrid way: the artist depicts Aaron in a royal Iranian robe; assistants are in Persian trousers; and on the top of the Temple is a statue of a Roman victory.

Hebrews 13:10–13 also situates its audience in a hybridized sacred time and space by inviting it to go to Jesus who was sacrificed for sin outside the camp and to endure with him there. In 13:15 it exhorts them ‘continually [to] offer a sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of lips that confess his name’ (NRSV). Just as the Jews in Dura-Europos returned to their sacred stories to remember the one to whom they offered ritual, Hebrews instructs its readers about whom alone to worship, and teaches that the sacrifice that God commands is praise.

References

Fine, Steven. 2005. Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Unknown Roman artist :

Relief from the Arch of Titus Rome, Roman soldiers carrying the golden menorah and other spoils from the Temple of Jerusalem, c.81 CE , Stone

Micah Bazant :

Refugees are welcome here , 2015 , Poster

Unknown artist :

Fragment from the Dura Europas synagogue, Completed 244 CE , Wall painting

A Subaltern City

Comparative commentary by Harry O. Maier

Many scholars think that the Letter to Hebrews was written to Christians in Rome during or shortly after the persecution of Nero in c.64 CE. It also may be situated when Jews in Roman Palestine rebelled against Rome in a revolt that lasted from 66 to 73 CE.

Hebrews is a letter that often reads like a sermon. Its chief aim is to exhort its audience to be more intentional in worship (2:1–3; 10:25), to remember that baptism has fundamentally re-oriented their commitments and ethics (6:1–8), and to be more diligent in expressing their identity (4:14; 10:23). It centres on the death of Jesus as a sacrifice for sin by contrasting his once for all atoning death with the need for repeated sacrificial offerings prescribed in the Hebrew Bible (8:1–13; 9:11–15; 10:1–18). Scholars have been rightly concerned that the letter thereby risks supersessionism. Hebrews 13, the letter’s concluding chapter, contains a series of exhortations that locates the audience in a world of suffering and struggle. It refers to imprisonment and torture (v.3); it exhorts listeners to go and join Jesus in the place he was crucified (vv.12–13). It is a subaltern text, that is, one that expresses the views of the marginalized and displaced (Gramsci 1934).

The Arch of Titus, erected to celebrate the emperor Titus’s posthumous divinization, shows the other side of this story. The arch is testament to Rome’s image of itself as a power blessed by Jupiter, in Virgil’s words, ‘with a rule without limit’ (Aen. 1.279) and to ‘rule the world…, to crown peace with justice, to spare the vanquished and to crush the proud’ (6.851–53). Hebrews urges its audience to stand firm in its opposition to such an order by remembering that Rome is not the eternal city; God’s rule alone is without end and believers are to look to the city to come.

Meantime, the listeners are to live in solidarity with one another by welcoming strangers and remembering the imprisoned and tortured. Micah Bazant’s Refugees Are Welcome Here poster was created during the Syrian refugee crisis to combat Islamophobia and racism. To welcome refugees—the stranger—is to live out the hope for another kind of city and social order, one that rejects the violence that makes a desert and calls it 'peace'. To welcome the stranger is to learn to be a stranger, to be with Jesus ‘who suffered outside the city gate to sanctify the people by his own blood’ (13:12 NRSV). Hebrews exhorts its audience to ‘go to him outside the camp and bear the abuse he endured’ (13:13 NRSV). This is not a call to masochism, but one of solidarity with those the global order marginalizes. For those in the twenty-first century West it is a call to resist the temptation to shelter behind city walls that shut others out by appeals to economic security, ethnocentrism, and suspicion of neighbour. ‘We can say with confidence, “The Lord is my helper; I will not be afraid; What can anyone do to me?”’ (13:6 NRSV).

Hebrews encourages this solidarity and courage by bathing its listeners with sacred narrative. They are to see the world through the lens of biblical story, specifically the stories of priestly sacrifice by which they are to understand Jesus’s self-offering for them. At the synagogue discovered at Dura-Europos a congregation of third century Jews surrounded themselves with vivid depictions of key events of their sacred tradition (the Exodus, Samuel’s Consecration of David, the Infancy of Moses, Ezekiel and the Dry Bones) as well as the ways in which they triumphed over opponents (Elijah vs. the Prophets of Baal; Esther and Mordecai; the Drowning of Pharoah’s Army). The Temple had long since been destroyed when they gazed upon the west wall facing Jerusalem and saw Aaron before the Ark of the Covenant ready to sacrifice a red heifer, bull, and goat (probably for purification/atonement). By remembering the Temple, they also expressed their longing for their city; by gazing on the animals offered for forgiveness, they were assured of God’s covenant with them even in this remote outpost of the Roman Empire.

The author of Hebrews calls for a sacrifice those synagogue worshippers would have practised: ‘a sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of lips that confess his name’ (v.15 NRSV). Hebrews 13 contains a paradox: a paradox in which those in the position of victims are the true bearers of promise. Thus, even as the assembly joins in solidarity with the imprisoned and tortured and suffers with Jesus ‘outside the camp’, it praises God by living his self-disclosure and seeking to embody the future she brings.

References

Gramsci, Antonio. 2021. On the Margins of History (The History of Subaltern Groups): A Critical Edition of Prison Notebook 25, ed. and trans. by Joseph A Buttigieg and Marcus E. Green (New York: Columbia University Press)

Commentaries by Harry O. Maier