James 1:1–11

That You May Be Mature and Complete

Christoph Weigel the Elder

Epistola Sancti Iacobi, from the Biblia ectypa (Pictorial Bible), 1695, Engraving, Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology, Emory University; Digital image provided courtesy of Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology, Emory University

A Steady Gaze

Commentary by David B. Gowler

Christoph Weigel’s Biblia ectypa (‘pictorial Bible’) consists of approximately 834 copperplate engravings that portray passages from, or represent books of, the Hebrew Bible and New Testament.

In the New Testament section, the majority of engravings interpret key passages from the narratives of the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation—Luke’s Gospel, for example, includes 68 images. By contrast, each Epistle is represented by only one engraving, with which it is introduced. The Epistle’s Latin title is inscribed above the image and its German title below. All the images of the Epistles depict their authors holding quills and either books or scrolls. Most of the authors are looking at visions from heaven that relate to key elements of the letter.

In this print, James sits, quill in hand, writing his Epistle. Instead of looking at the vision above and behind him, he gazes steadily into a mirror, reinforcing the Epistle’s lesson that its readers should not be like those who observe their reflections and later forget what they look like (1:23–24). The Epistle contrasts ‘natural’ mirrors with the ‘perfect law of liberty’. In a tradition of employing mirrors metaphorically to symbolize practices of self-examination and moral improvement, Weigel thus denounces people who look at the perfect law of God but allow it to make no lasting impression on them, praising instead those ‘doers who act’ and ‘persevere’ (1:25).

In the background, the wind—personified by a head in the clouds blowing on the sea—creates great waves, a reminder not to be double-minded and doubting, driven and tossed by the wind (1:6–8; see also Peter walking on the water, Matthew 14:22–33). As the sun rises, a flower wilts in its scorching heat, denoting that the rich will suffer the same fate (1:9–11).

These negative metaphors illustrate the devastating consequences that befall those of inadequate, immature, incomplete, or inactive faith: they are unstable people at the mercy of the wind. As James notes, faith without works is dead (2:18–26).

Weigel’s engraving, like James’s Epistle, argues that wealth provides only a brief illusion of security: the rich will be humbled and fade away like flowers in withering heat—just as the grass of the field, in Jesus’s teachings, is ‘thrown into the oven’ (Matthew 6:30; see also Job 24:24; 27:21). In contrast, James urges its readers, as does Weigel’s engraving its viewers, to put their faith into action.

Unknown Artist

The Martyrdom of James, mid-18th century (?), Oil on canvas, St James Cathedral, Jerusalem; Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem

A Steadfast Faith

Commentary by David B. Gowler

The Armenian Cathedral of Saint James stands where tradition holds that Jesus ‘ordained the Apostle James, Brother of the Lord, as the first bishop of Jerusalem’ (Atajanyan 2003: 15; Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.1.2). The cathedral—seat of the Armenian Patriarchs—is located in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem and named for both James of Jerusalem and James the Apostle, son of Zebedee—hence the cathedral also is referred to as Saints James Cathedral.

Most images of James the brother of Jesus in the cathedral thus depict him as the first bishop of Jerusalem (e.g. on the episcopal chair, wearing bishop’s robes).

Another title given to James, ‘the Righteous’ (or ‘the Just,’ the earliest reference of which is Gospel of Thomas 12), stresses both James’s faithfulness to the law and his place in a tradition of righteous sufferers (Painter 2004: 112; James 5:6). Thus, other visual representations in the cathedral, like this painting on the south wall of the cathedral’s main sanctuary, show his faithful endurance of the ultimate trial: martyrdom.

James stands on the ‘parapet’ (pterugion) of the Temple, bearing witness to his faith (Clement of Alexandria, and Hegesippus in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.1.4; 2.23.11–16). Hegesippus (c.110–180 CE) has James declare that Jesus sits ‘at the right hand of the great Power’, so James’s gaze and right hand guide viewers to an image of God seated in heaven at the upper left of the composition. Seated to the right of God the Father is Jesus, holding a cross, which likely also foretells that James’s martyrdom is near, with the Holy Spirit, depicted as a dove, above them. Although the physical resemblance between Jesus and James is not as strong in this image as it is in many other visual representations, the colour of their mantles connects them as do their martyrdom stories.

James’s martyrdom is depicted on the right side of the painting. The upper section shows him falling after being thrown from the Temple’s parapet, while below he is shown kneeling in prayer, as a man with a fuller’s club prepares to strike him. In Hegesippus’s version (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.8–18), James prays, as did Jesus on the cross, for God ‘to forgive them, for they know not what they do’ (Luke 23:34; see also Stephen in Acts 7:60) in a final act of faithful endurance.

References

Atajanyan, Emmanuel. 2002. The Armenian Sanctuaries in Jerusalem (Moscow: Slovo)

Gowler, David B. 2014. James Through the Centuries (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell)

Painter, John. 2004. Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press)

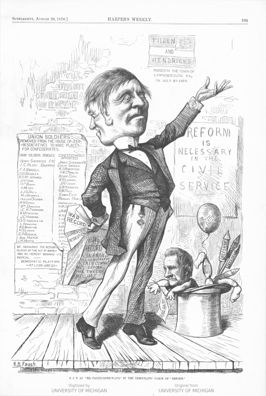

A. B. Frost

‘S. J. T. as “Mr. Facing-Both Ways”’, in Harper’s Weekly, August 26, 1876, Print, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University; p. S705., Courtesy HathiTrust Digital Library

‘Mr. Facing-Both-Ways’

Commentary by David B. Gowler

A.B. Frost, ‘the dean of American illustrators’, was famous for his images portraying rural life and sport in an unpretentious and often humorous fashion. Early in his career, however, Frost was an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, a magazine based in New York City, who created biting, satirical political cartoons during the infamous 1876 U.S. presidential election.

Scandals during the Grant administration and an economic depression caused by a bank panic in 1873 made the Democrats’ message of civil service reform and improved monetary policy attractive to voters. Samuel Tilden, Democratic candidate for president, thus portrayed himself as a reformer and proponent of sound fiscal policy.

Frost’s cartoons attack Tilden as corrupt, accuse him of Confederate sympathies, and support instead the campaign of the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes.

The cartoon ‘Mr. Facing-Both-Ways’ has its roots in how the biblical term ‘double-souled’ (dipsychos in James 1:8) has been used to attack opponents. Such allusions build on John Bunyan’s 1678 The Pilgrim’s Progress (which introduces the character of ‘Mr. Facing-both-ways’—a man whose soul is divided between faith and the world), Goethe’s Faust (1808), and A. H. Clough’s Dipsychus (1850).

Frost’s two-faced Tilden alludes to the politician’s alleged hypocrisy. Tilden’s ‘public’ face declares his support of reform. The mostly hidden second face, however, directs viewers to consider his alleged Confederate sympathies, the Democratic Party’s support of ‘soft’ money (paper money not backed by gold), and corruption (Democrats in the House of Representatives fired staff who were Union veterans and hired Confederate veterans).

The document Tilden hides behind his back contains other accusations: Tilden was a ‘copperhead’, a northern Democrat opposed to fighting the Civil War, and a ‘sham reformer’ because of his early connections with the corrupt Boss Tweed Ring.

Thomas Hendricks, the Democratic vice-presidential candidate, also appears in this cartoon at the lower right as a ‘rag-baby’ crawling out of Tilden’s top hat—a caricature signalling his own support for ‘soft’ money, whose inflationary effects are suggested by the rising balloon. The ‘fireworks’ of reform also emerging from the hat allude to the flashy and sometimes spectacular appearance of reform that was, in reality, ephemeral.

Tilden’s apparel also reflects his status as a rich corporate lawyer. Frost believed the multimillionaire Tilden corruptly gained his fortune by representing titans of industry. In terms of James’s Epistle, Tilden was one of the greedy, corrupt rich who should ‘wither away’ (v.11).

References

Gowler, David B. 2014. James Through the Centuries (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell)

Christoph Weigel the Elder :

Epistola Sancti Iacobi, from the Biblia ectypa (Pictorial Bible), 1695 , Engraving

Unknown Artist :

The Martyrdom of James, mid-18th century (?) , Oil on canvas

A. B. Frost :

‘S. J. T. as “Mr. Facing-Both Ways”’, in Harper’s Weekly, August 26, 1876 , Print

Likeness to Jesus

Comparative commentary by David B. Gowler

This Epistle’s apparently self-effacing introduction, ‘James, a servant of God and the Lord Jesus Christ’ (1:1), exudes an authority that allows its author to issue multiple commands to his ‘brothers and sisters’ without further detailing his qualifications.

Who is this James, and why does he have such authority? The author appears to claim to be James the brother of Jesus (Hartin 2004: 90–93), the primary leader of the Jerusalem church (e.g. Acts 21:17–26). He is also known as James the Just (or ‘Righteous’), because of his reputation for piety and faithfulness.

The Gospel of Thomas, part of the Gnostic Library found at Nag Hammadi, Egypt, even has Jesus himself declaring that James was to be the leader of the disciples (logion 12).

Church tradition has understood the reference to ‘the brother of Jesus’ in three principal ways. The first explanation is that, following the virgin birth of Jesus, the ‘brothers and sisters of Jesus’ (e.g. Mark 3:31–32) are younger children of Joseph and Mary (the Helvidian theory). The doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary led others to identify Jesus’s ‘brothers and sisters’ as children of the widower Joseph by a previous marriage (the Epiphanian theory, which became dominant in the East). The Hieronymian theory, which became preferred in the West, argues that the ‘brothers and sisters’ of Jesus are his cousins, and that James is the apostle, James the son of Alphaeus (Luke 6:15).

Because of their family relationship, some traditions stress how similar James was to Jesus ‘in body, in visage, and of manner’ (The Golden Legend, c.1275), and visual representations of James thus often bear a striking resemblance to Jesus. This led some to speculate that, for those arresting Jesus, Judas Iscariot’s kiss in Gethsemane was necessary to distinguish Jesus from his brother James (Bedford 1911: 3–4).

In many representations, James holds a book or a scroll to symbolize that he is the author of part of Scripture, as we see in Christoph Weigel’s Biblia ectypa. This engraving, like the Epistle’s opening verses, introduces some major themes of the letter: endurance of trials, active faith, concern with poverty and wealth, and having right understanding, speech, and action.

James is not only Jesus-like in his history of visual representation. The Epistle only names Jesus twice (1:1; 2:1), but echoes of his teachings permeate the letter, especially the Sermon on the Mount (e.g. James 1:2, 4, 5–6, 10, 17, 19–20). More than other New Testament Epistles, James’s Epistle communicates the message, mind, and heart of Jesus (Hartin 2004: 101–07). Both Jesus and James, for example, focus on Torah obedience—declaring that loving one’s neighbours means taking care of their physical as well as spiritual needs (e.g. Leviticus 19:15–18; James 2:8, 14–18). James uses Greek terms that stress the degradation of the poor and the greediness of the rich (e.g., ptōchos, ‘degraded poor’; plousios, ‘greedy rich’; Batten 2008: 72–73).

The Epistle argues that faith becomes ‘mature and complete’ through enduring various trials and tribulations (1:2–4), and traditions about James stress his piety, devotion to prayer, holiness, asceticism, a maturity of faith like that his Epistle celebrates in Abraham (2:21–24) and Rahab (2:25), and an endurance like Job’s (5:11).

Images of his martyrdom, like that in St James Cathedral in Jerusalem, are rare until the twelfth century. Church tradition states that because of his piety and faithfulness, James was thrown from the parapet of the Temple before finally being killed by one or more strikes with a fuller’s club—some ancient sources mention stoning (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 20.9.1; Hegesippus, in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.8–18)—so other images of James sometimes include him holding a fuller’s staff, club, or flat bat and, less often, wearing a fuller’s hat.

Just as God is ‘single-minded’ in the sense of giving generously to ‘all’ (1:5), believers should be single-minded in their response of faith/trust in God, including confidence in prayer (1:6; see Matthew 21:22). The ‘double-souled’ (dipsychos) person displays the opposite characteristic (1:7–8), and James urges its readers instead to choose friendship with God, not friendship with the world (see 4:4).

Dipsychos is not found in extant literature antecedent to James, but a comparable idea is found in Jewish texts (e.g. the ‘double heart’ of Psalm 12:2; Sirach 1:28) and Greek texts (e.g. the ‘double man’ of Plato’s Republic 397E). The term was later used in theological debates to attack one’s opponents (e.g. Athanasius, Defence of the Nicene Definition 2.4). It is the reverberations of such usages that can be traced in more recent accusations about ‘two-faced’ people, such as A. B. Frost’s satirical cartoon about Samuel Tilden—those who, unlike James, are not ‘mature and complete’ with a faith that endures.

References

Batten, Alicia. 2008. ‘The Degraded Poor and the Greedy Rich’, in The Social Sciences and Biblical Translation, ed. by Dietmar Neufeld (Atlanta: SBL), pp. 65–77

Bedford, Richard. 1911. St James the Less (London: Quaritch)

Gowler, David B. 2014. James Through the Centuries (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell)

Hartin, Patrick J. 2004. James of Jerusalem (Collegeville: Liturgical)

Commentaries by David B. Gowler