Matthew 5:1; 7:28–29

The Sermon on the Mount

Jan Brueghel the Elder

The Sermon on the Mount, 1598, Oil on copper, 26.7 x 36.8 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 84.PC.71, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

Righteousness of the Heart

Commentary by Lyrica Taylor

In this tiny painting, Christ stands behind a makeshift podium slightly to the left of the centre of the painting, his head highlighted by a halo of luminous yellow. Much of the crowd of people around him listens intently, while some seem distracted or uninterested. The artist seems to ask whether we, the viewers of this painting, are listening to Christ’s message. Or are we (like the group of five figures in the right foreground) more interested in the day’s gossip? Are we distracted by material goods, like the woman in a sumptuous yellow dress in the left foreground who pats a dog while a gentleman offers to buy her a pretzel? Do we trust in God’s guidance or do we try to control the future ourselves by consulting fortune-tellers, such as the well-dressed man in the left foreground who is having his palm read?

Eleven of the disciples stand behind Christ, signifying their belief in Christ’s teaching, and also indicating (by their number) Judas’s future betrayal of Christ. Christ’s simple dress suggests a focus on his words rather than on outward appearance. The crowds represent people from all of society, from the rich wearing elaborate silk gowns to the poor wearing simple cloaks, and suggest the wide range of people in the New Testament who came to hear Christ’s message.

Jan Brueghel the Elder’s Sermon on the Mount, like many contemporaneous Dutch and Flemish paintings that depicted Christ or John the Baptist preaching outdoors to sixteenth-century crowds, was painted during the Reformation, when the importance of studying Scripture, made more accessible through sermons, was being emphasized. By including so many engaging interactions between the figures, Brueghel encourages the viewer to look closely and see how true righteousness of the heart flows outwards in our relationships with other people, in our worship, in how we use our time, and in how we use our wealth.

Cosimo Rosselli

The Sermon on the Mount and the Healing of the Lepers, 1481–82, Fresco, 349 x 570 cm, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palace, Vatican State; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Teaching in Action

Commentary by Lyrica Taylor

In Cosimo Rosselli’s Sermon on the Mount, executed for the Sistine Chapel, the lower half of the composition is filled with about 100 figures. The figural groupings imitate the undulating lines of the hills, creating dynamic shapes that keep the viewer’s eyes moving across the composition that includes at least three distinct points in time.

At the centre left, Christ stands (rather than sits, as in Matthew 5:1) on a small hill. His right hand is raised in a gesture of declamation, indicating that he is about to begin his sermon, asking for the attention of the crowd, and signifying the importance of his teaching. The crowds stand and sit closely to the left and in front of Christ. The use of both imagined ancient and contemporary clothing, as well as the incorporation of an Italian town on the left and a church at the top of the mountain, thus incorporate past and present in the work, and underscore that Christ’s authority and teaching span both time and location. The disciples sit just behind and to the right of Christ.

Slightly right of centre and in the background, Christ leads his disciples down from the mountain after the sermon is over (Matthew 8:1). Finally, in the right foreground, Rosselli continues to draw on Matthew 8 by showing Christ healing a leper (Matthew 8:2–4). The leper, whose skin is covered with sores, kneels before Christ, who is stretching out his hand to heal him. This scene of healing may refer to the main theme of the Sermon on the Mount of true righteousness, not the external righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees (as perhaps represented by the bearded man wearing a long purple robe standing behind the leper), but righteousness of the heart. Christ’s care for the leper in need flows out of his righteous character into his relationship towards other people, moving from teaching to practical ministry.

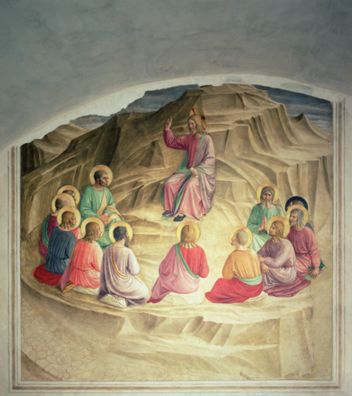

Fra Angelico

The Sermon on the Mount, Cell 32, 1442, Fresco, 190 x 198 cm, Museo di San Marco, Florence; Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy / Bridgeman Images

Summit of the Law

Commentary by Lyrica Taylor

In this serene fresco by the Italian Dominican friar Fra Angelico, Christ sits on a rocky shelf at the centre of the composition, a little above his disciples, with his right hand raised in a gesture of teaching. In his left hand he holds a scroll, possibly referring to the Traditio Legis, or giving of the law, as seen in early Christian iconography.

The scroll signifies Christ’s perfect fulfilment of the Law as described a few verses later in Matthew 5:17–20 and his teaching of true righteousness, the main theme of the Sermon on the Mount. This true righteousness is not an external righteousness gained merely by following rules and regulations, but instead is a greater inner righteousness of the heart, pointed to by the Law, that can only come from repenting of sin, and trusting and following Christ.

Christ’s halo is inscribed with a cross, signifying his divinity and thus the divine authority of his teaching. His gesture and the scroll recall traditional Byzantine images of the Pantocrator that depict Christ as ascended into Heaven and as ruler and judge of all, and that connect the worshipper to Heaven through him. Several of the disciples sit with their backs to the viewer, thus drawing the viewers in—inviting them to become participants. Each of the disciples is slightly individualized, giving a diversity of figures and thus pointing to the reach of Christ’s teaching and salvation to all.

All of the disciples look at Christ and are intently focused on his teaching. No crowds are depicted; instead, Fra Angelico included a minimum amount of detail in order to keep the focus continually on Christ. The warm, vibrant colours of the figures’ robes and their semi-circular arrangement draw our attention and guide it towards Christ’s teaching. The figures sit in a strikingly steep and rocky mountain landscape. The height of the mountain may suggest the supremacy of God’s laws over those created by human rulers.

Jan Brueghel the Elder :

The Sermon on the Mount, 1598 , Oil on copper

Cosimo Rosselli :

The Sermon on the Mount and the Healing of the Lepers, 1481–82 , Fresco

Fra Angelico :

The Sermon on the Mount, Cell 32, 1442 , Fresco

‘As One Who Had Authority’

Comparative commentary by Lyrica Taylor

Fra Angelico’s fresco in the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence, Cosimo Rosselli’s fresco in the Sistine Chapel, and Jan Brueghel the Elder’s oil on copper painting each contain exquisite renderings of the event of the Sermon on the Mount, and each conveys a specific understanding of Christ’s sermon, described in Matthew 5 and 7:

Matthew 5:1–2: Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down his disciples came to him. And he opened his mouth and taught them.

Matthew 7:28–29: And when Jesus finished these sayings, the crowds were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as their scribes.

Fra Angelico’s beautiful fresco is part of a larger programme of over fifty frescoes depicting the life of Christ that the artist and his assistants created for meeting rooms and cells of the lay brothers, novices, and clergy. The Sermon on the Mount is in a room likely to have been a study for the convent’s lector and used as a classroom, and is opposite the library. The focus in Sermon on the Mount on Christ’s teaching is thus especially appropriate for this cell. By solely focusing on the act of Christ teaching and the reception of his teaching by the disciples, Fra Angelico’s fresco reflects the relatively small community of men who would have viewed this image, and who belonged to an order that valued education. The disciples serve as the exemplar and show the friars how to learn and from whom to learn. Indeed, the friars’ lives are in themselves a form of commentary on the Sermon on the Mount as they lived out Christ’s teaching on how true righteousness is applied in everyday life—in our relationship to God in worship, to material things, and to other people; and not for applause of men or reward.

Rosselli’s Sermon on the Mount is part of a fresco cycle on the central sections of the north and south walls of the Sistine Chapel. Directly opposite the Sermon on the Mount on the north wall, Rosselli created a fresco on the south wall depicting Moses receiving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai and the Israelites and the golden calf below. He used a similar composition of landscape and figures in both paintings to emphasize the connection between the two events and between the Old Testament and the New Testament, in a typological pattern of prefiguration and fulfilment. By depicting the disobedience of the Israelites who sacrifice to a golden calf at the very time when Moses is receiving the Ten Commandments, Rosselli shows our ultimate inability to keep the Law and our need for Christ’s atoning sacrifice. In Sermon on the Mount, Rosselli shows Christ who perfectly fulfilled the Law and offers us his salvation.

By including so many intricate details in his tiny painting, Brueghel invites the viewer to look closely at the numerous interactions between the figures. Through these interactions, the artist reflects on human nature, with people’s outward appearances and their actions revealing their hearts. While frequently humorous, these actions often convey a warning to the viewer about letting the things of this world distract us from our need of Christ’s salvation. While Fra Angelico and Rosselli chose to depict Christ as a large figure, easy to identify, in Brueghel’s painting the viewer must look closely to find him. Brueghel thus suggests that we as the viewers must be purposeful in focusing on Christ in our lives, and not allowing ourselves to be distracted. Brueghel also provides an important message through the young girl at the lower right corner who observes the bones of an animal, a memento mori, reminding the viewer not to put faith in the things of this world, but in Christ.

These artworks by Fra Angelico, Rosselli, and Brueghel put the focus on the act of teaching by Christ, on the authority of his teaching, and on the importance of listening to his teaching and allowing it to transform our minds and hearts. All three works show Christ’s perfect fulfilment of the Law and his teaching of true righteousness that begins in the heart, forms our character, and flows outward. Instead of gaining righteousness through external observation of rules and regulations, these works show that the Law points to a greater righteousness, a true righteousness that only comes from trusting Christ, from repentance of sin, and from following Christ.

References

Blumenthal, Arthur (ed.). (2001). Cosimo Rosselli: Painter of the Sistine Chapel (Winter Park, FL: George D. and Harriet W. Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College)

Bonsanti, Giorgio. 1998. Beato Angelico: Catalogo completo (Florence: Octavo, Franco Cantini Editore)

Gabrielli, Edith. 2007. Cosimo Rosselli: Catalogo ragionato (Torino: Umberto Allemandi)

Honig, Elizabeth. 2016. Jan Brueghel and the Senses of Scale (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press)

Hood, William. 1993. Fra Angelico at San Marco (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Jaffé, David. 1997. Summary Catalogue of European Paintings in the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Pfeiffer, Heinrich. 2007. La Chapelle Sixtine révélée: L'iconographie complète (Paris: Éditions Hazan)

Woollett, Anne T., and Ariane van Suchtelen (eds). 2006. Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, with Waanders)

Commentaries by Lyrica Taylor