Matthew 6:16–34; Luke 12:22–34

Seek Ye First the Kingdom of God

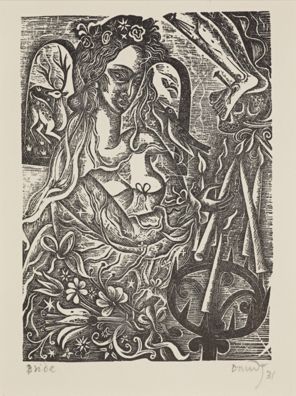

David Jones

Bride, 1931, Wood engraving on paper, 140 x 110 mm, Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge; DJ 14, © Estate of David Jones / Bridgeman Images. Photo: © Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge / Anthony Hynes 2010

Pray Then in This Way

Commentary by Elizabeth Powell

The towering goddess of David Jones’s wood-engraving Bride rises from the earth, her clothes indistinguishable from the lilies of the field, her hair like a flowing river toward which a deer, seen through the window at the left, draws near. Her conversation partner is a small black bird seated on another windowsill at right. Crowned with roses and stars, she lights a votive candle, offering her prayer before the Lord of living creatures on the cross. The devotion of this Mother Earth figure is imagined as a wedding place where inner and outer, heaven and earth, spirituality and materiality, mingle and intertwine—a gathering of the polyphonic voices of creation in a hymnic sacrifice of praise.

When Christ teaches his disciples how to pray, he turns them away from excessive wordplay, extreme displays of piety, and the anxious hoarding of treasures. He counsels them to turn instead to Mother Earth: ‘Consider the lilies of the field’ (Matthew 6:28; Luke 12:27); ‘look at the birds of the air’ (Matthew 6:26; Luke 12:24).

The injunction of the Gospels to tend to the organic forms of the lilies and the birds has more prescience now than ever before. The exploitation and destruction of the earth’s natural abundance is rooted precisely in such anxious greed and wilful forgetting of the native wisdom of the land, sky, and sea.

As we seek collective repentance and conversion as members of this delicately intertwined world, so might our prayers also need renewal (Christ suggests), through these practices of responsive listening to the diverse voices of creation all around us.

Jones conceived his wood-engraving Bride while illustrating Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Ancient Mariner whose final stanza aptly concludes our meditation here, too:

Farewell, farewell, but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast. (Coleridge 2005: 80)

References

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. 2005. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, illustrated and intro. by David Jones, ed. by Thomas Dilworth (London: Enitharmon Press)

Vincent van Gogh

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, Oil on canvas, 50.5 x 103 cm, The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; s0149V1962, David Tipling Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Look at the Birds of the Air

Commentary by Elizabeth Powell

In Vincent van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows, a tidal wave of yellow fields mounts against a moody sky of ocean blues. A muddy road, hedged in green, impels its way through the centre of the canvas then halts abruptly before this infinite expanse.

Whilst elsewhere in Van Gogh’s work, blues and yellows swirl magnificently together in an enchanted dance, here the primary colours starkly delineate sky from field, heaven from earth. Only the black crows freely transgress, passing lightly between the two.

As one of the last paintings Van Gogh was to create, the seemingly dead-end road at its centre is often seen as a symbol of the end of his own artistic labour, a kind of scar of his finite existence on the earth. Indeed, his heavy use of impasto technique draws attention to the painting as the work of his hands, just as the wheatfields are emblematic of human labour more broadly. But perhaps Van Gogh is not simply anticipating an end here, but asking, to what end is this labour?

With the flight of the birds, our eyes lift from the enveloping yellow toward that which is beyond it. Their minimalist black forms prompt us, with the Gospels, to remember this ‘more than’ value of our life and work:

Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they? (Matthew 6:26; Luke 12:23–24)

In freely receiving their ‘daily bread’, the birds take flight and are fortified for their upward ascent. Might these black angels be signifiers not of despair but of hope, anticipations of our final crossing into the eternal rest of the Father from whom, through whom, and to whom all things are made (Romans 11:36)?

Paul Cézanne

Tulips in a Vase, c.1890, Oil on canvas, 59.6 x 42.3 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection; 1933.423, Art Institute of Chicago / Bridgeman Images

Consider the Lilies of the Field

Commentary by Elizabeth Powell

In Paul Cézanne’s still-life paintings, ordinary domestic objects—here a bouquet of flowers and assortment of stray oranges—become the objects of contemplation. As viewers of this painting, we have nothing to do but look, and delight in, these forms of everyday life.

The Vase of Tulips is cheerful and serene as a field of floral colours emerges within a luminous environ of turquoise blues and lavender pinks. Delicate yellow meadow flowers jostle with white daisies, while red annunciatory tulips open triumphantly within a jungle of leaves. The clay vase in which they rest is clothed in a green glaze that mirrors the viridity of the life it contains.

This still-life painting enjoins us, with the Gospels, to be still and ‘consider the lilies of the field’ (Matthew 6:28; Luke 12:27). Without silent contemplation, the inherent beauty and radiance of such everyday objects remain mute, and ourselves unchanged. From his own sustained practice of sitting before Cézanne’s paintings, the poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, articulated the wisdom he discerned thus:

[H]ow related one thing is to the next, how it gives birth to itself and grows up and is educated in its own nature, and all we basically have to do is to be, but simply, earnestly, the way the earth simply is, … not asking to rest upon anything other than the net of influences and forces in which the stars feel secure. (Rilke 2002: 69)

The art of still-life invites us to return to the miracle of the present moment, to remember amidst the everyday troubles of life that ‘there is a today; it is’ (Kierkegaard 2018: 76). What might it mean for us to ‘still’ our own lives so as to discover anew the daily gift and wonder of existence? Matthew 6 suggests that to ‘strive first for the kingdom of God’ (v.33; Luke 12:31) is, paradoxically, to learn the art of resting upon the Father in all things.

References

Kierkegaard, Søren. 2018. The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air: Three Godly Discourses, trans. by Bruce H. Kirmmse (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Rilke, Rainer Maria. 2002. Letters on Cézanne, ed. by Clara Rilke, trans. by Joel Agee (New York: North Point Press)

David Jones :

Bride, 1931 , Wood engraving on paper

Vincent van Gogh :

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890 , Oil on canvas

Paul Cézanne :

Tulips in a Vase, c.1890 , Oil on canvas

Do Not Worry

Comparative commentary by Elizabeth Powell

The enduring simplicity of the Lord’s Prayer given in Matthew 6 is couched within a myriad of warnings about how not to pray and how not to work, culminating in the injunction not to worry: ‘Therefore, I tell you, do not worry.... And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life?’ (v.27). Interwoven among them is the continual return of focus upon ‘Our Father in heaven’ (v.9): ‘your Father knows what you need before you ask him’ (v.8); ‘your Father who sees in secret will reward you’ (v.4); ‘your heavenly Father will also forgive you’ (v.14); ‘and indeed your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things’ (v.32).

Throughout Jesus’s sermon, worry, greed, and obsessive self-focus are shown to malform like a disease. Worry, it seems, is particularly toxic, for this natural response to the uncertainties of life becomes mistaken as a kind of remedy—we cling to worry and spin ever more fruitlessly. There is no promise there won’t be trouble or things to worry about—indeed, its reality is affirmed as a perpetual aspect of each day. But the Gospels invite us to exchange patterns built up by the habit of worry with the habit of prayer—with the ‘Our Father.’ In this, the lilies and the birds become our teachers.

The growth of the flower is purported to outwit and outshine even the Hebrew sage and king, Solomon himself, bequeathing to whomever would sit before her a way of life made beautiful by this contemplation of nature’s wisdom. Paul Cézanne’s Vase of Tulips gathers these wordless forms of grace in a clay vessel, inviting us, too, to be still and behold their bounded yet bountiful appearing.

The crows cutting across the wheatfields and trembling skyline of Vincent van Gogh’s oil painting recall the scandalous birds of Christ’s sermon: not earning their keep, yet recipients of divine favour, ‘your heavenly Father feeds them’ (Matthew 6:26; Luke 12:24).

The bride of David Jones’s wood-engraving, clothed in the lilies of the field, attunes her ear to the bird who joyfully sings before the cross. On the hill of Golgotha—literally, the place of the skull—Jesus does not teach as one who keeps himself in a realm above or separate from the troubles and concomitant worries which infect and inflict our existence, but who has plumbed its depths, wedding our weakness indissolubly to divinity’s healing grace.

The lily’s effortless becoming and the birds’ shameless reaping what they haven’t sown flies in the face of a certain sense of human justice; of an insistence on what is mine and getting what one deserves. But the birds and the lilies return us decisively to the realm of gift: ‘what do you have that you have not received? If then you received it, why do you boast as if you did not receive it?’ (1 Corinthians 4:7).

From the lily, we remember the very gift of our existence as creatures unfolding in time, and from the bird we remember that the fields are still our heavenly Father’s way of feeding us, too. Even when agriculture is mechanized, the dependency we have on labour that is not our own and systems we do not control can remind us not to boast. Humility and thankfulness become the seedlings from which a more just society can spring, drawn by the light of the living God who attends, cares for, and sees all that is done in the earth, on street corners and in secret rooms, perceiving physical needs as clearly as intentions of the heart.

To take the birds and lilies as our teachers is not to deny or take flight from the necessities and often brutal realities of existence, but to (re)discover a wisdom by which we may become more fully and truly human within them. In his meditations on this passage, philosopher Søren Kierkegaard suggests we learn from the lily and the bird the art of being silent before the Creator in order to pray, ‘Holy is Your Name’; to practice obedience in order to yield to the words, ‘Your will be done’; and to discover joy in the labours of mutual forgiveness and in the hope of ‘Your kingdom come’ (Kierkegaard 2018: 5).

Together with these works of human hands—Cézanne’s bouquet of tulips in a clay vase; Van Gogh’s crows over a cultivated wheatfield; Jones’s engraved bride making her vow—we may listen anew with the gospel for the secret of the lily and the bird as an antidote to the heady elixir of worry which encumbers our daily lives, learning once more this way of life infused by the continual return to ‘Our Father’.

References

Abram, David. 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: Vintage Books)

———. 2011. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (New York: Vintage Books)

Kierkegaard, Søren. 2018. The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air: Three Godly Discourses, trans. by Bruce H. Kirmmse (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Elizabeth Powell