Matthew 12:46–50; Mark 3:31–35; Luke 8:19–21

Who are my Mother and my Brothers?

James le Palmer

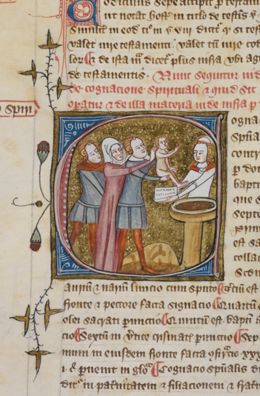

Cognacio (Spiritual kinship), from Omne Bonum (Absolucio-Circumcisio), 1360–75, Manuscript illumination, The British Library, London; Royal 6 E VI, fol. 317v, © The British Library Board (Royal 6 E. VI, fol. 317v)

Absent Parents

Commentary by Michael Banner

Jesus’s assertion that those who do the will of God are ‘my mother, and sister, and mother’, proposes a kinship outside and beyond the family. This proposal took concrete social form in a number of ways in early Christianity—but perhaps none quite so widespread as in the invention of the institution of godparenthood.

Within the large C of the entry for Cognacio Spiritualis (Spiritual Kinship), the illuminator of this early encyclopaedia represents a baptism by which this new, spiritual kinship was created. Godparents were chosen from outside the family circle—that is, they were not related to the child by blood or marriage. And here three godparents (two men and one woman, which was the norm for a boy) rather insistently present a naked child to the priest who stands, liturgical booklet in hand, at a plain font.

They are encircled and held together by the entry’s initial letter, just as in virtue of the sacred rite in which they are jointly taking part they are united in a spiritual kinship with the child, with the child’s worldly relatives, and with each other.

When infant baptism was first practised (it became the norm by no later than the fifth century), the pre-existing rite demanded that someone should make the promises candidates would originally have made for themselves. It seems this role was first taken by parents, but parents were increasingly replaced in this role from the fifth century onwards by those who would come to be thought of as godparents, and parents were formally forbidden from being godparents to their own children by the Synod of Mainz in 813 (Lynch 1986).

A rite of initiation for the newborn conducted in the absence of parents is rather remarkable, and shown here (in its high medieval form) the parents are not simply pushed to the sidelines but out of the picture altogether. True enough they were responsible for seeking baptism for their infant, and for selecting the godparents, but they typically had little or no part in the rite itself.

And what that rite did was to represent and create parallel kinship, beyond the immediate family group, relating the child to the wider community, and providing him or her with mentors with a special care and responsibility for their spiritual growth—relativizing the claims of mothers, brothers, sisters, and other ‘natural’ kin.

References

Lynch, J.H. 1986. Godparents and Kinship in Early Modern Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

John Singer Sargent

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882, Oil on canvas, 221.93 x 222.57 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124, Photo: © 2021 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Unrelated Relations

Commentary by Michael Banner

‘Four corners and a void’ was the judgement of a grumpy critic on John Singer Sargent’s picture (Hirshler 2009: 204), protesting at his disregard for the normal conventions of portraiture which would have placed the human figures centrally and would have had them fill the space. As it is, the four sisters (from the youngest looking at us from the gentle-blue expanse of rug, to the oldest in profile at centre left, leaning against the outsized yet elegant vase), are distributed across, and occupy rather little of, the room they are in. The room recedes towards what would be a simple block of inky darkness were it not for a mirror over a mantelpiece which reflects further space and light, suggesting that this is a vestibule or hallway.

A hallway is, of course, a place of arrival and departure, a threshold between inside and outside. And the girls, in their gradation from youngest to oldest, are placed progressively nearer to this threshold—for growing up is typically held to involve a certain sundering of family ties. Even now they seem to exist within this composition as four individuals, related to each other by a similarity of looks and dress but by no mutual engagement. And the oldest already turns away. She is named (in the picture’s current title) patriarchally, as one of the daughters of Edward Boit. But in the normal expectation of things, she would be the first to cross the threshold, perhaps to acquire a different name in a reconfiguration of her family ties, and perhaps also acquiring others she would now call brothers or sisters, or even mother or father.

When, at the beginning of Jesus’s ministry, his family comes in search of him, and Jesus is inside, and his family are outside on the threshold, it is as if he has already turned away from them, and a reconfiguration of his family ties has already occurred. But as his words indicate, he has not joined himself to another kinship, but is fashioning his own.

References

Charteris, Evan. 1927. John Sargent (New York: Scribners)

Hirshler, E.E. 2009. Sargent’s Daughters: The Biography of a Painting (MFA Publications: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Unknown artist, South Germany

The Holy Kinship, c.1480–90, Polychromed wood, 128 x 112.5 x 27 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2002.13.1, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Extending Kinship

Commentary by Michael Banner

As the cult of the Virgin Mary developed, and piety demanded that her virginity be perpetual (Pomplun 2008), the Gospels’ references to Jesus’s ‘brothers’ posed a problem. From another perspective, however, it was Jesus’s seeming lack of blood relations which was troubling—especially so, perhaps, in the late Middle Ages when a nexus of extensive family ties seemed socially indispensable.

These two problems—Jesus having relatives he shouldn’t, and seeming to lack ones he should—were effectively solved by the emergence of a legend concerning Anne, whom early Christian tradition identified as Mary’s mother. She sits at the visual centre of this polychrome carved altarpiece (probably originally from the Cistercian convent of Kirchheim in southern Germany), a skilfully choreographed portrait of Jesus’s imagined and extensive family.

The Protoevangelium of James from the second century is the first written source to give Mary’s mother a name. Much later tradition held that Anne had three husbands—here bunched amicably behind her. After the death of Joachim (Anne’s first husband and Mary’s father), these further husbands were said to have provided Mary with two sisters, seated at left and right in the front row, and each—like Mary—with a husband standing squarely behind her. The progeny of the sisters gave Jesus six cousins (who could equally be termed ‘brothers’ argued some exegetes, though some preferred to hold that these brothers were Joseph’s sons from earlier marriages), and legend identified these cousins as some of Jesus’s closest apostles and disciples.

Thus, with the development of Anne as a holy yet fecund, thrice-married matriarch, Mary’s virgin status was preserved, while Jesus’s ministry becomes something of a family business, relying on the sort of bonds crucially important in medieval life. The solidarity of the group is here expressed not only by their harmonious arrangement and interaction, but also by the choice of playthings of two of his young cousins at the feet of their mothers. They toy with a bunch of grapes, alluding to the wine of the Eucharist which would have been celebrated before this altarpiece, and thus to the sacrifice towards which Christ’s life, and that of his imagined ‘brothers’ and wider family, is directed.

References

Pomplun, Trent. 2008. ‘Mary’, in The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism, ed. by James Buckley, Frederick Bauerschmidt, and Trent Pomplun (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons)

James le Palmer :

Cognacio (Spiritual kinship), from Omne Bonum (Absolucio-Circumcisio), 1360–75 , Manuscript illumination

John Singer Sargent :

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, South Germany :

The Holy Kinship, c.1480–90 , Polychromed wood

Redeeming Kinship

Comparative commentary by Michael Banner

In a marginal note at Luke 8:21, the Rheims Bible of 1582 states that ‘our spiritual kindred is to be preferred before carnal cognation’. In a Catholic translation of the Bible, made in the midst of the Counter-Reformation, this was a polemical point aimed at the Protestant Reformers, who had rejected canon law’s formalisation of ‘spiritual kinship’ as creating numerous (and unpopular) impediments to marriage amongst spiritual kin. But it also seems to anticipate a tension between worldly and spiritual kinship, with the latter properly claiming first place.

The Markan version of the story of Jesus’s mother and brothers coming in search of him is coloured by an earlier verse which explains their purpose: hearing about the beginning of his teaching and healing ministry, and his calling of the disciples, ‘they went out to seize him, for people were saying, “He is beside himself”’ (3:21). This detail is absent in Luke and Matthew, but in Mark’s story sharpens Jesus’s question ‘Who are my mother and my brothers?’, making it seem like a repudiation of them. And indeed, they play no part in Mark’s Gospel.

The so-called Holy Kinship associated with the intensely popular cult of St Anne (a set of beliefs about Mary’s family ties and a related iconographic motif, which we see represented here in the fifteenth-century carved altarpiece from Germany) pictures a quite different relationship between Christ and his earthly family. Here he is firmly embedded in a network of kinsfolk, reaching backwards to his grandmother, grandfather, and two step-grandfathers (as we might put it), and forwards to his cousins who, even as babes-almost-in-arms, have been recruited to the support of this dynasty’s star. This rich imagining, is, of course, impelled by reverence for Jesus’s mother, Mary, who is all but absent from Mark’s Gospel, and central only to the birth narratives in Matthew and Luke. Here, however, with her mother Anne, she assumes a prominent place in a tightly and harmoniously fashioned group-portrait of a matriarchal clan.

It is ironic, that the sweeping away by the Reformers of the cult of the Holy Kinship as biblically unwarranted occurred at the same time as the notion of spiritual kinship was likewise rejected as biblically unsound. This meant, however, that although baptism, of course, persisted, it became increasingly ‘familiarized’—that is to say, that the parents steadily took a more prominent role, and godparents were more and more likely to be chosen from amongst the child’s relatives. The stark reality depicted in the illuminated initial of an initiation rite from which parents and other relatives were banned—and the naked child is handed over to strangers who will become kin—lost some of its starkness in virtue of this ‘familiarization’. With it, something was also lost of the challenge which the rite posed to exclusive claims for carnal kinship.

Christianity, however, did not typically set the two kinships against one another. The commentary from the Rheims Bible’s margin may warn us against falling in too readily with the demands of ‘natural’ kinship. But the artist who sculpted the ‘Holy Kinship’ altarpiece accomplished something of a wonder in showing what the ‘natural’ might spiritually achieve. It unifies this potentially disparate group, with all its centrifugal forces, in a diverse yet harmonious company. And the genius of the legend is surely the same as the genius of the sculpture: to represent the living and the dead, different generations, males and females, and all those siblings and cousins, not as discordant rivals (as they might be), but as collaborators in an extraordinary joint and spiritual enterprise.

Such collaboration amongst carnal kin is not to be taken for granted. As Augustine liked to say, the first founder of the earthly city (Cain) was a fratricide, as was the founder of the capital of the earthly city (Romulus) (Augustine City of God, 15.5). The Holy Kinship should not be read, then, as a mere assertion of the merits or claims of carnal kinship, but as an exercise in imagining the redemption of those ties, and their reconciliation with the claims of spiritual kinship (perhaps especially by means of the Word of God present on the knee of his mother, to whom the Scriptures, on the knees of her sisters, bear witness).

The profound harmony of this image with its affectionate and tightly knit group, contrasts sharply with the quite different harmony of Singer Sargent’s brooding portrait of the four daughters. For all that it is deeply satisfying as a picture, the harmony of its elements is not a harmony between the girls, who seem to exist in isolation one from another. For all that carnal kinship is often termed ‘natural’, the naturalness of such kinship can sometimes seem anything but inevitable.

Commentaries by Michael Banner