Matthew 8:23–27; Mark 4:35–41; Luke 8:22–25

Calming the Storm

Unknown English artist

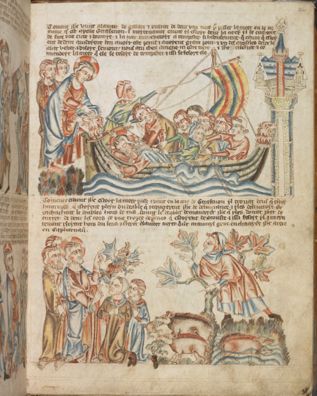

The Calming of the Storm; the Devils are cast out and enter the Gadarene Swine, who are then drowned, from the 'Holkham Bible Picture Book', c. 1327–35, Illumination on parchment, 285 x 210 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 47682, fol. 24r, © The British Library Board (Add MS 47682, fol. 24)

Hand of God

Commentary by Kelly Schumann Andino

This late medieval Anglo-Norman Bible depicts the Calming of the Storm at the top of the page and the healing of the Gerasene demoniac (Mark 5:1–20) below. The image of the Calming underscores the subtle intervention of the incarnate God-made-man.

The illumination can be read as a ‘moving picture’ (in Art History, a ‘synoptic narrative’), the story progressing from left to right. First, at left, Christ enters the boat in blue and red garments accompanied by two disciples. Christ is barefoot and bent forward, climbing into the vessel. His head is graced by a cruciform halo, underscoring his divinity.

The first scene blends fluidly into the second, united by the boat occupying the bulk of the composition. Within the boat (in the second scene) Christ appears again, sleeping in the midst of his disciples. The ship is reminiscent of William the Conqueror’s eleventh-century kingly vessel the Mora (seen in the Bayeux Tapestry), built in the style of Viking longships, with striped sails and lion-like carved figureheads. Christ reclines at the stern surrounded by eight men, three of whom struggle to control the vessel. The large sail strains against the wind, ropes billowing as waves jostle below. Two sailors look towards the storm; the rest look to Jesus for deliverance. Jesus rests with his eyes closed and his arm folded under his head.

Blinded by fear, the disciples consider their Saviour indifferent (Mark 4:38–40). One disciple attempts to wake Jesus. It seems that Jesus slumbers on, but look closely: Christ intervenes, extending his left hand toward the waves below, in a gesture of benediction. The gentle hand of the God-man calms the turbulent seas.

Jesus hears the pleas of his terrified disciples and acts. He is not indifferent. When it may seem the Messiah sleeps, in fact, God speaks: ‘Peace, be still’ (Mark 4:39).

Paul Abraham in collaboration with Manish Soni

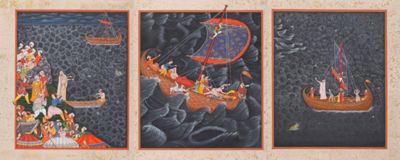

Calming the Storm (Triptych), from Sarmaya commission Issanama, 2017–18, Opaque watercolour and natural pigments on hand-made paper, Each sheet: 615 x 505 mm, Sarmaya Arts Foundation, Mumbai; 2018.33.8; 2018.33.9; 2018.33.10, © Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Rebuking the Demon

Commentary by Kelly Schumann Andino

Contemporary artist Manish Soni employs the style of sixteenth-century Mughal miniatures to plant Jesus deep in the artistic tradition of the Indian subcontinent. This triptych is part of the Issanama commission, an artistic collaboration between the founder of Sarmaya Arts Foundation Paul Abraham and traditional miniaturist and third-generation artist Manish Soni of Bhilwara, Rajasthan. The Issanama, ‘the Epic of Jesus’, offers a fresh model of art patronage for the contemporary era, one in which the patron enters into an intellectual dialogue with the artist. The commission illustrates episodes from the Bible and the life of Jesus Christ in the exquisite landscape of the Hamzanama, the earliest expression of the Indian subcontinent’s celebrated Indo-Islamic art tradition.

An ambitious undertaking, the Issanama presents Christ’s story as relevant to all cultures and at home in any age. The use of rich colours and detailing, characteristic of imperial Mughal style, give the triptych an air of authority. Jesus is depicted as physically larger than other characters, highlighting his central role in the drama, and his divine status.

The triptych presents three scenes. At left, Jesus stands on shore surrounded by the crowd, preparing to depart by rowboat for a larger sailing vessel beyond. Similar to the imperial court, onlookers boast rich garments and rest under colourful tents. In contrast, Jesus stands in a simple robe, distinctive Mughal patka sash tied at his waist, with a cloak (rather than a turban) draped over his head. Jesus looks at the people, while gesturing towards the sea—inviting his disciples towards the waves.

At centre, Jesus sleeps in a crimson blanket as violent black waves toss the boat. Ten disciples struggle in the vessel. One is thrown overboard as another tries to hold him fast. One disciple surveys the sea from the mast. Only a single disciple goes to Jesus, prodding him.

The tempest is driven by a demonic figure, seen behind Jesus in the upper left. With two wide eyes, a human nose, and fanged mouth, Satan hopes to consume the boat and all inside.

At right, Jesus stands with hand raised, blessing the now pacific sea. The waves recede. In top left, the demon is reduced to a small, smiling horned creature. Soni reveals the storm as demonic, testing the faith of the disciples—yet Christ reigns, even over demons. Jesus dwarfs his disciples, who are seen exhausted, relieved, full of wonder. ‘Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him? (Mark 4:41).

References

'Inside the Issanama: The Art, the Conversations, the Muse, 25 January 2019', available at https://sarmaya.in/spotlight/inside-the-issanama/ [accessed 28 April 2022]

Eugène Delacroix

Christ Asleep during the Tempest, c.1853, Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 61 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.131, www.metmuseum.org

Interior Tempest

Commentary by Kelly Schumann Andino

In this dark, moody composition, the French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix uses colour and movement to suggest a psychological, interior tempest. There is as much drama within the boat as without.

Despite his professed atheism, Delacroix was fascinated with this topic, painting many iterations. This version is among his later works. In some variants the boat features sails; here Jesus sleeps in a simple rowboat, surrounded by nine disciples. This vessel moves by human power against the churning, emerald sea.

Jesus reclines in the stern, his head propped against his right hand. An azure blue mantle is draped around his head and shoulders. His white tunic gapes open at the chest. A dazzling gold aureole crowns Christ’s head, drawing the viewer’s eye.

The disciples are in distress. None looks to Jesus for direction. Their garments are a dusky rainbow of colour: vermilion, lilac, chartreuse, sapphire, and sepia. At centre, one bare-chested disciple looks outwards, as if towards the viewer, throwing his arms into the air, cloak billowing in the wind. Will the storm cast him overboard? Or will he find the anchor, as his right hand, searching, reaches back towards the Lord?

Three disciples struggle against the oars, one nearly toppling into the waves. Seen from behind, their bare backs reflect the stormy light. Behind Jesus, one disciple in a Phrygian cap guides the rudder. Another disciple, with white beard and turban, clutches the prow.

Emotionally, the painting invites the viewer into the distress of the disciples. ‘Teacher, do you not care that we are perishing?’ (Mark 4:38). There is no evidence of a miracle. The only calm is the face of the sleeping Saviour. Cloudy skies and shadowy distant mountains portend a disquieting future. The sea itself echoes the turbulence of the nineteenth century and the disciples the unbelief of Delacroix.

Unknown English artist :

The Calming of the Storm; the Devils are cast out and enter the Gadarene Swine, who are then drowned, from the 'Holkham Bible Picture Book', c. 1327–35 , Illumination on parchment

Paul Abraham in collaboration with Manish Soni :

Calming the Storm (Triptych), from Sarmaya commission Issanama, 2017–18 , Opaque watercolour and natural pigments on hand-made paper

Eugène Delacroix :

Christ Asleep during the Tempest, c.1853 , Oil on canvas

What Sort of Man is This?

Comparative commentary by Kelly Schumann Andino

What sort of man is this, that even the winds and the seas obey him? (Matthew 8:27)

Fear grips the hearts of the disciples as they find themselves flung into a storm on the Sea of Galilee. Their Rabbi—their long awaited Saviour—is sleeping. Was it not he who called them out into the boat?

Here, three artists offer their interpretation of the miraculous event in Mark 4:35–41, Matthew 8:23–27, and Luke 8:22–25. The works here span five centuries but are connected by themes of faith, discipleship, and salvation. The relationship between the Lord and his disciples takes centre stage as they confront a threat beyond human control.

The artist of the Holkham Bible blends two scenes together to show a progression of events: first the Lord’s approach to the boat, and then the miracle itself. Interestingly, the artist departs from the Gospel accounts and depicts Christ miraculously intervening while still asleep. This choice invites the viewer to a greater faith, even exceeding that of the disciples, who roused Jesus to request his help. The eyes of the disciples look to Jesus, and even as they believe that he is doing nothing, Jesus acts. His divine hand moves to quell the waters. Salvation comes as the God-man intervenes to help his perishing disciples, though not in a way they might expect.

The oil painting by Eugène Delacroix approaches the story differently. The composition is more focused; only one scene is portrayed. Christ sleeps as the disciples struggle in the storm. The miraculous action of God is not portrayed; it is either left to the viewer’s imagination, or perhaps rejected entirely. The faith of the disciples is shaken as they look elsewhere for deliverance. None looks to Jesus—he seems forgotten.

‘Why are you afraid, O men of little faith?’ (Matthew 8:26). Delacroix masterfully captures the haunting light of the storm, employing a range of colours. The mood hints at a psychological tempest as much as a physical one. Salvation in this painting is not shown and not guaranteed. The intellectual temper of a more religiously-uncertain, post-Enlightenment modernity contextualizes the doubt expressed in this painting.

The triptych by Manish Soni retells the story anew in an Indo-Islamic idiom, employing the style of sixteenth-century Mughal miniatures. Soni brings out the full story, portraying the miraculous event in three scenes. The demonic figure in the second panel interprets the storm as the work of Satan, designed to test the disciples. Do they trust their Master? They don’t, but this proves no obstacle to Jesus’s display of messianic power.

Jesus dwarfs the disciples as he calms the sea and rebukes the demon, perhaps connecting this story with that of the Gerasene demoniac immediately preceding (or following, depending on the Gospel). Soni might favour a more literal translation of Mark 4:39 as ‘Silence, be muzzled’, instead of ‘peace, be still’, to connect the story with Christ’s language of exorcism. Invisible spiritual realities are made visible, and Christ’s miraculous power is unveiled. Here we see the epic style of Indo-Islamic visual narrative married with a more twenty-first century desire to document the exact events in question.

All three works feature the boat—and the disciples within it—as the centre of the drama. The boat is an image of the Church, sheltering and guiding believers in the voyage to eternal life. At first, the disciples attempt to withstand the storm by human power alone. Jesus wishes to teach them about faith, trust, and the importance of seeking God for deliverance. The storm cannot be overcome, the Church cannot be guided through turbulent seas, without divine guidance. The disciples need to learn to trust in the care of their Saviour.

In all three works, Jesus sleeps wrapped up in garments, prefiguring his ‘sleep’ in death when he will be wrapped in burial clothes and laid in the tomb between crucifixion and resurrection. Salvation comes when Christ wakes from sleep. In the tempest, the disciples come to Christ with a faith that is failing, without trust. Jesus saves them anyway.

‘What sort of man is this?’ (Matthew 8:27). He is the God-man, but not all will see him that way. The medieval artist of the Holkham Bible certainly sees Jesus as divine; but Delacroix’s portrait is more human—no miracle is shown, even if the glowing aureole hints at divinity. Soni wants us to believe, but based on the facts of the miracle in question; he wants everything spelled out. Like the disciples, we must see the miracle to believe.

Even as they witness a miracle, Christ invites his disciples to greater faith, greater trust. First, they must let go of the fear that clouds their vision, in order to see clearly. Then they will recognize him, as the God-man, the Saviour, commanding the wind and the rain.

Commentaries by Kelly Schumann Andino