Matthew 8:28–34; Mark 5:1–20; Luke 8:26–39

The Gerasene Demoniac

Unknown artist [Milanese?]

Healing of the Possessed Man of Gerasa, from Magdeburg Ivory panels, c.962–68, Ivory, 13 x 11 x 0.8 cm, Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt; Zip Lexing / Alamy Stock Photo

Jesus Heals the Gerasene Demoniac

Commentary by Klazina Botke

An anonymous tenth-century artist presents the story of the healing of a possessed man in this small ivory carving. With its open worked checkerboard background, originally layered with a copper plate, the relief was part of a larger narrative of the story of Christ, told in fifty or sixty similar ivory carvings. These were probably made for some form of liturgical furniture in the cathedral of Magdeburg. Only sixteen of these Magdeburg ivories have survived today (Jülich 2007: 85–6).

The artist has chosen the exact moment when Christ is ordering a demon to leave the man’s body. In this powerful symmetrical composition, we see Christ in profile on the left. Behind him—somewhat close and cramped together—are the twelve disciples. Peter is the most prominent, with his keys in his right hand (Matthew 16:19; 18:18), while further to the back some of the disciples are indicated only by their hair.

The right side of the relief is taken up by the possessed man, a winged demon flying out of his mouth (the head of the demon has broken off), and a person constraining him. By including this latter figure, the artist seems to refer to the verses where the possessed man is being described as wild, and difficult to hold down (Mark 5:4; Luke 8:29). Three small pigs are looking up curiously at the scene in front of them, still unaware of their impending fate.

In the Gospels the demon reveals his name as ‘Legion’, ‘for we are many’ (Mark 5:9; Luke 8:30). A legion was a unit of around 6000 men in the Roman army, so this could be seen as a direct allusion to the contemporary Roman occupation of Palestine (Boring 2006: 151). By expelling ‘Legion’ from the possessed man, Christ’s power is surpassing even that of the greatest earthly power of his time.

In this ivory carving, his superior authority is visualized. There is a monumentality to Christ’s figure even though the ivory object itself is relatively small, and there is a decisiveness in the gesture of his right hand as it points towards the demon. These elements create an important clarity, helping the beholder immediately to recognize and understand Christ’s power.

References

Boring, M. Eugene. 2006. Mark: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press)

Jülich, Theo. 2007. Die mitteralterlichen Elefenbeinarbeiten des Hessischen Landermuseum Darmstadt (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner)

Lasko, Peter. 1994. Ars sacra, 800–1200 (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Paul Bril

Healing of the Possessed Man of Gerasa, 1601, Oil on copper, 27 x 36 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich; inv.no. 876, bpk Bildagentur / Alte Pinakothek, Munich / Art Resource, NY

A Whimsical Landscape

Commentary by Klazina Botke

The man healed by Christ is still raving, flapping his arms around, and needs to be restrained by two other people. Meanwhile, the herd of demon-possessed pigs is running towards the cliff behind them, jumping into the water in sheer panic. A cloud of dust surrounds the drowning animals. This narrative is played out in the foreground of an overwhelming landscape: a river scene with an imaginary Italianate port, jagged rocks on either side of the water, and a monumental tree on the left. The smooth surface of the copper support enabled subtle details and luminous colours. There is a transition from brown in the foreground, via shades of green, to blue and white on the horizon, creating a dramatic light and depth. The high viewpoint adds to this. Looking down on the landscape, we can see far into the distance, the biblical figures in the foreground becoming even smaller.

Paul Bril, born in the south of the Netherlands, was trained as a painter in Antwerp. He travelled to Rome in the early 1570s where he became one the most influential landscape painters of his day, together with his brother Matthijs. He was especially well-known for his large fresco cycles in Roman palaces. Although the two brothers played an important role in the development of the genre, autonomous landscape painting was still regarded as one of the lower art forms in Italy, and distinctly inferior to narrative painting. Without making concessions to the quality of his dramatic and whimsical landscapes, Bril could increase the status of his paintings by including a biblical scene.

Jesus, his disciples, the possessed man, and the swine, all inhabit Bril’s landscape, but they do not dominate it. Rather, they are shown to be part of a greater whole. In this connection, Bril’s landscape may help us to reflect on how this biblical episode points to a wider world beyond the Jewish people. The healing took place near Gerasa (in Mark 5:1 and Luke 8:26) or Gadara (in Matthew 8:28) which was part of the Decapolis, a group of ten cities on the eastern frontier of the Roman empire. It is therefore the only exorcism in the Synoptic Gospels that takes place on Gentile territory.

So as the demoniac was sometimes read as representing Gentiles in general (e.g. Ambrose, Luke 8), one could say that Jesus did not only free an individual from a demonic power but offered healing to a wider world as well—a world beautifully represented here by Bril (Boring 2006: 151).

References

Berger, Andrea. 1991. Die Tafelgemälde Paul Brils (Münster/Hamburg: Lit verlag)

Boring, M. Eugene. 2006. Mark: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press)

Wood Ruby, Louisa. 1999. Paul Bril: The Drawings (Turnhout: Brepols)

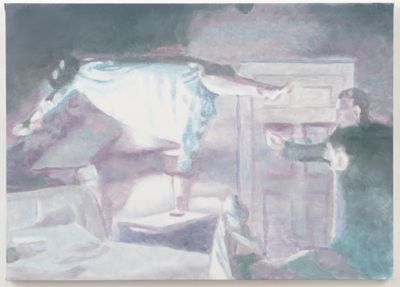

Luc Tuymans

The Exorcist, 2007, Oil on canvas, 84.8 x 118.4 cm, Private Collection; © Luc Tuymans, Courtesy Studio Luc Tuymans; Photo: Peter Cox, Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

The Exorcist

Commentary by Klazina Botke

This ethereal image is part of Luc Tuyman’s series of nine paintings on religion and the potent power of the Jesuit Order, created on the occasion of a solo exhibition in Antwerp entitled Les Revenants. Tuymans’ work often deal with the question how shocking and disastrous events from a recent past can be told, and how we determine our attitude towards such events. Reality and illusion are often merged in his paintings, as are beauty and discomfort (Molesworth 2011: 17–18).

This particular work is made after a movie still from The Exorcist (1973), directed by William Friedkin after a novel by William Peter Blatty. Based on the real-life event of an exorcism of a boy in Maryland (USA) in 1949, the story deals with Father Merrin and Father Karras, two Jesuit priests, trying to expel a demon from a twelve-year-old girl.

The film is often loud, threatening, and dark, whereas the painting is the opposite. The soft blue, purple, white, and grey colour tones generate a ghostlike effect, while the abstraction of the scene creates a certain stillness. Tuymans’s figures remain vague, without faces and therefore anonymous. This gives the beholder a feeling of distance, an effect the artist may have desired. As Tuymans once declared: ‘The two most important misunderstandings regarding my work concern “poetry” and “intimacy”. My work is anything but intimate’. (Dexter & Heynen 1994: 9).

Tuymans chose one of the most iconic scenes from the movie: the girl is levitating above her bed while the two clerics attempt to exorcise her possessor by repeating the line, ‘The power of Christ compels you’. Near the end of the movie, in his last attempt to heal the girl, Karras commands the demon to enter him. Once possessed, he jumps out of the window and dies. Parallels with the Gospels will not have been lost on the viewer.

References

Dexter, Emma, and Julian Heynen (eds). 1994. Luc Tuymans (London: Tate)

Koerner, Joseph Leo. 2011. ‘Monstrans’, in Luc Tuymans, ed. by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth (Brussels: Ludion), pp. 31–47

McDannell, Colleen. 2008. ‘Catholic Horror. The Exorcist (1973)’, in Catholics in the Movies, ed. Colleen McDannell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 197–225

Molesworth, Helen. 2011. ‘Luc Tuymans: de schilder van de banaliteit van het kwaad’, in Luc Tuymans, ed. by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth (Brussels: Ludion), pp. 15–29

Unknown artist [Milanese?] :

Healing of the Possessed Man of Gerasa, from Magdeburg Ivory panels, c.962–68 , Ivory

Paul Bril :

Healing of the Possessed Man of Gerasa, 1601 , Oil on copper

Luc Tuymans :

The Exorcist, 2007 , Oil on canvas

The Power of Christ

Comparative commentary by Klazina Botke

Of the many references to exorcisms in the New Testament, the healing of the Gerasene demon (Mark 5:1; Luke 8:26), or two Gadarene demoniacs (in Matthew 8:28), is one of the most compelling. Mark develops it at greatest length and with greatest relish, but in all three versions the performance between Jesus and the demon in the presence of the disciples and the herdsmen, has a public and theatrical dimension. Following on directly from Jesus’s calming of the storm, this miracle seems to build towards even more spectacular heights: Jesus is shown to control not only the wild elements of nature, but has mastery over a demon that appears at times to assume the power of a whole army. His victory over it is given a visible demonstration unlike any of the other Gospel exorcisms.

Both the tenth-century ivory carving and the painting by Paul Bril in this exhibition recount the miracle as described in Luke and Mark. When the demon speaks, he immediately shows a certain respect towards Jesus. We understand he feels threatened since he has recognised him as the Son of God (Mark 5:7; Luke 8:28). He starts begging not to be expelled to a different land or into the abyss (Luke 8:31), knowing that he is less powerful than the person in front of him. When Jesus drives the demon out, he tells the healed man to ‘Go home to your own people and tell them how much the Lord has done for you, and how he has had mercy on you’ (Mark 5:19). The performance therefore also becomes an instrument for converting gentiles to belief in Christ; through the exorcism the word of Christ’s miraculous power is spread.

The ivory relief represents the exact moment when the devil is leaving the body of the possessed man. The composition is simple but effective, and the artist managed to capture many aspects of the story. Jesus is represented as larger than the other figures, underlining his authority and command of the situation.

What happens just moments afterwards is represented by Paul Bril more than six centuries later. In his rendition, the struggle of the man being healed is still palpable as the herd of swine, now possessed by the demon, runs off a cliff leaving behind a large cloud of dust. The demon’s choice to be cast into pigs can be explained by their classification in Jewish Law as ‘unclean’ (Leviticus 11:7–8). Bril’s detailed telling of the Gospels is dominated by the magnificent scenery that takes up most of the space in this composition. Whereas the ivory relief was meant clearly, and only, to narrate the story of the exorcism and Christ’s power, Bril seems to be concerned with expressing something more: devotion, the overwhelming beauty of the land, and—perhaps above all—Christ’s control over it.

The ritual of exorcism, or the act of driving out and warding off demons or evil spirits from people who are believed to be possessed, was a defining feature of early Christianity. One of the earliest petitions for an exorcism can be found in the Apostolic Constitutions, a fourth-century collection of treatises intended as a manual for the clergy, where it was considered a gift of healing: ‘May he that rebuked the legion of demons, and the devil, the prince of wickedness, even now rebuke these demons which have turned away from piety’. It was believed that God could give human’s the charism of casting out these demons, and in the following centuries the act of exorcism transformed into a liturgical performance drawing upon priestly authority (Young 2016: 28).

By telling the story of the demonic possession of a 12-year old girl—and her mother’s attempt to rescue her through an exorcism by priests—William Friedkin’s 1973 movie The Exorcist harnessed modern people’s continued fear of demons, and enabled him to create one of the most successful horror movies of the twentieth century. Belgian artist Luc Tuymans (1958) adopted a specific still from the movie for his 2007 series of paintings on the power of the Jesuits. The famous scene in which the two Jesuit priests keep chanting ‘The power of Christ compels you’ is still recognisable, but stripped of its dark colours, movement, and sound, becomes ghostly and distant in Tuymans’ painted interpretation. This makes the beholder reflect in yet another way on the Gospels’ message of the power of Christ. Here invoked by priests, this power seems something ethereal—transcending our world (as befits divine power), but by the same token elusive, detached, and out of reach.

References

Barton, John, and John Muddiman (eds). 2007. The Oxford Bible Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Boring, M. Eugene. 2006. Mark: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press)

Levack, Brian. 2013. The Devil Within (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Oden, Thomas C., and Christopher A. Hall (eds.). 1998. Mark, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, New Testament, 2 (Downers Grove: Inter Varsity Press)

Young, Francis. 2016. A History of Exorcism in Catholic Christianity (London: Palgrave Macmillan)

![Healing of the Possessed Man of Gerasa, from Magdeburg Ivory panels by Unknown artist [Milanese?]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/aw0821_unknown_healing-of-the-possessed-man-of-gerasa.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Klazina Botke