Matthew 9:1–8; Mark 2:1–12; Luke 5:17–26

The Healing of the Paralysed Man

Unknown artist

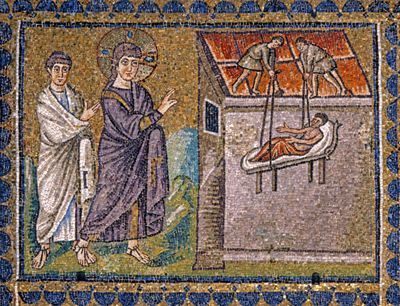

Jesus Healing the Paralytic at Capernaum, 5th–6th century, Mosaic, Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna; Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY

A Way In

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Situated high on the north wall of the nave of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, this mosaic is one of thirteen panels in a sequence depicting Jesus’s public ministry.

Throughout these panels the mosaicist's (or mosaicists') focus is on the principal actors in each Gospel episode. So—notably—there is no crowd in this design, although a gathering is mentioned in all three versions of the narrative.

The absence of the crowd here was probably at least in part a practical decision. The panels are high up and relatively small. Viewed from the floor of the nave, the subject of this design can be readily recognized. The panel would be more difficult to read if it included lots of smaller figures.

The focus on the main people in the story could also have an exegetical function: to direct the viewer to the central event—the miracle of healing by Jesus.

A millennium and a half after the creation of the Sant’Apollinare mosaics, the English artist Eric Gill employed a similar economy of figures in his Stations of the Cross for London’s Westminster Cathedral. Writing pseudonymously, Gill explained that he had omitted the crowd from his designs so that the worshippers could enter into that role (Rowton: 1918).

The absence of attendant figures in the Sant’Apollinare mosaics—including the missing crowd in the miracle at Capernaum—could be viewed in a similar way. The worshipper—or the tourist—in Sant’Apollinare Nouvo can inhabit the roles of those in the narratives who are not depicted. Contemplating this episode, they might ‘become’ the crowd.

Visitors to Sant’Apollinare Nouvo might of course find themselves quite literally in a crowd—in the congregation at the liturgy, or in a throng of tourists. In gathering there for a communal experience, they recall the people assembling to listen to Jesus in Capernaum. That crowd gathered to hear Jesus preaching, but also hindered access to him for a vulnerable person.

Viewing this episode in situ, we might also experience something of the paralysed man’s perspective: from the distant floor of the nave, this Jesus seems relatively inaccessible. But in a congregation gathered in his name, he assures his followers that he is present (Matthew 18:20).

Inhabiting these different roles in the narrative, we might ask ourselves whether we are conscious of who is included and excluded from our congregations, and how the healing activity of Jesus might be present now.

References

Rowton, E. 1918 ‘The Stations of the Cross in the Cathedral’, Westminster Cathedral Chronicle, 12: 50–53

Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg

The Paralytic Lowered Through the Roof to Christ (Verlamde door het dak naar Christus neergelaten), 1624–39, Engraving, 311 x 236 mm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Purchased 1885, RP-P-1885-A-9080, Courtesy of Rijksmuseum

The Clamour of the Crowd

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg presents us with a mass of bodies. The crowd fills almost all of the image and spills out of the open door to the right.

Amid this hubbub, a man on a bed is being lowered through the ceiling by four other men.

The scene is chaotic and claustrophobic.

Van Swanenburg has depicted the event just as it is described in Mark and Luke. But the Gospel writers do not tell us how the crowd gathered around Jesus reacted to the man appearing through the roof. Van Swanenburg imagines a range of responses among the assembly.

Several of the faces are astonished at the sight. Others look anxious at the precarious manoeuvre—will he make it down safely? Some reach up to help. A few appear to be disgruntled—perhaps they are annoyed that the man is ‘pushing in’ to get past them to Jesus.

Jesus’s own expression is a mixture of surprise and concern. He leans backwards as the man is lowered towards him, and his arms are open at his sides. This gesture suggests both astonishment and a readiness to receive the man who is being lowered to him.

But Jesus’s arms are not just open to the man on the bed. His gesture is directed out of the frame and so appears to invite us as viewers into the scene. If we are part of this gathering, we might reflect on whether we recognize ourselves in any of the reactions of the crowd to this event.

Stanley Spencer

The Paralytic Being Let into the Top of the House on his Bed, c.1920, Oil on panel, 29.8 x 33 cm, Private Collection; © Estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images; Photo: © Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries, London / Bridgeman Images

Filled with Awe

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Stanley Spencer had worked as a hospital orderly in Macedonia during the First World War and must have encountered soldiers paralysed in conflict. The paralysed man in this biblical narrative may therefore have put him in mind of his wartime experiences.

But Spencer sets the scene neither in Macedonia, nor in the biblical Capernaum, but in his home village of Cookham in Berkshire, England, which was the setting for many of the artist’s biblical paintings.

The house is that of Spencer’s next-door neighbours, and the ladders belong to a local builder (Christie’s: 1999). These real-life, local details embody the event in the artist’s own time and place. The Gospel narrative is not just something that happened in first-century Capernaum. It is a miracle that is relived in day-to-day village life.

As Mark describes, a crowd is spilling out of the house where Jesus is preaching (2:2). Jesus himself is not seen in this image because we are viewing the event from outside.

Closely following the narrative in Mark and Luke, Spencer depicts the paralysed man being lowered through a gap in the roof of the house.

Among the onlookers in this scene, some figures on the left are bending backwards to watch the precarious manoeuvre, and to the right, another figure views it from a tree. They are witnessing a feat of human ingenuity in the hoisting of the man through the roof, but a greater cause for amazement is about to occur inside.

This image is therefore one of anticipation and hope for the miraculous in this time and place.

References

Christie’s. 1999. ‘Lot Essay: Sir Stanley Spencer, R.A. (1891-1959), The Paralytic Being Let into the Top of the House on his Bed’, https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-1472090 [accessed 21 December 2020]

Unknown artist :

Jesus Healing the Paralytic at Capernaum, 5th–6th century , Mosaic

Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg :

The Paralytic Lowered Through the Roof to Christ (Verlamde door het dak naar Christus neergelaten), 1624–39 , Engraving

Stanley Spencer :

The Paralytic Being Let into the Top of the House on his Bed, c.1920 , Oil on panel

So Many Gathered

Comparative commentary by Naomi Billingsley

The house is so crowded that some have to peer in from the open door. But there is a man who cannot walk, who has to be carried. And he needs to get to Jesus, the man that everyone is there to see and listen to.

This predicament is described vividly by Mark and Luke. The solution: find another way into the house, by opening the roof and lowering the paralysed man to Jesus.

Matthew’s account of this miracle does not describe how the man was brought to Jesus, only that he was being carried on a bed (9:2). And the crowd is only mentioned at the end of Matthew’s narrative, where they are filled with awe at seeing the man walk (9:8).

The Ravenna mosaicist, Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg, and Stanley Spencer have all focused on the version of events in Mark and Luke, where the man is lowered through the roof of a house. But each artist presents us with a different perspective on this precarious operation.

Van Swanenburg captures the chaos of the crowd inside the house and the man being lowered into their midst. This commotion contrasts starkly with the visual economy of the Ravenna mosaic, where the crowd is absent, and the event appears to be taking place outside the house. Spencer also situates us outside, but in his painting the main event is taking place inside, so we only see the crowd spilling out of the door and the man being lowered into the roof.

Crowds can be places of both celebration and persecution; both joy and danger; and both inclusion and exclusion. Throughout the Gospels, there are numerous narratives that show how fine the lines can be between the different roles that crowds can play.

In the story of the healing of the paralysed man at Capernaum, the crowd is an apparently happy gathering of people who want to listen to Jesus (Mark 2:2; Luke 5:17). But it also attracts the suspicion of the scribes and Pharisees (Mark 2:6; Matthew 9:3; Luke 5:21). And it hinders the paralysed man’s access to Jesus (Mark 2:4; Luke 5:19).

Spencer’s depiction of the crowd overflowing from the house seems to emphasise the crowd as a happy gathering in his home village of Cookham. He shows a village coming together, not just to listen to speaker inside the house, but also to help the paralysed man to find a way in. A local labourer has lent the ladders (Christie’s, 1999), and other villagers are stopping to watch the man being lowered (rather than joining the crowd peering into the house for a glimpse of Jesus).

Some of van Swanenburg’s figures are also community-spirited, helping to guide the man safely down to Jesus. But others look discontented, suggesting that they do not want this man to join their crowd.

There is no crowd in the Ravenna mosaic, but its focus on the man being lowered through the roof can give viewers pause to consider what prevented an easier route to Jesus.

In spring 2020, crowds suddenly became a threat in all parts of the globe. Large gatherings seemed to offer not security but danger, and rapidly became alien to everyday experience. Images like van Swanenburg’s print that is almost overflowing with figures and Spencer’s painting where people spill out of the house suddenly looked strange. They became a reminder of both the problems of close proximity, and of lost freedoms and conviviality. Reflecting on such images and narratives in light of the experience of a time without crowds, we might consider what sorts of gatherings we most value and most need for our flourishing.

References

Christie’s. 1999. ‘Lot Essay: Sir Stanley Spencer, R.A. (1891-1959), The Paralytic Being Let into the Top of the House on his Bed’, https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-1472090 [accessed 21 December 2020]

Commentaries by Naomi Billingsley