Matthew 4:1–11; Mark 1:12–13; Luke 4:1–13

The Temptation of Christ

Bartholomäus Bruyn the Elder and workshop

The Temptations of Christ, 1547, Oil on canvas, 184 x 119 cm, LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn; Inv. Nr. 58.3., AKG-images

The Devil You Know

Commentary by Carla Benzan

Martin Luther is cast as the devil in this painting of the Temptation of Christ which forms part of an altarpiece made for a Carmelite monastery in Cologne. Painted when the Catholic Church viewed Protestantism as a dangerous heretical movement north of the Alps, this work brings biblical history into direct conversation with the recent past.

Bartholomäus Bruyn focusses on the first temptation, which unfolds on a barren plateau of rock beside a figure of an unknown episcopal patron (kneeling at bottom left). The notorious Reformer offers a rock in his left hand. The index finger of his right hand hovers just above it, the curled knuckles of his other fingers lightly grazing its surface. Luther’s gesture stands out against his distinctively Protestant black robes, focussing attention on the demand ‘If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread’ (Matthew 4:3).

The pointing index finger of Christ’s left hand echoes that of Luther’s right hand only to reject his provocation. Whereas Luther’s other hand clutches the stuff of the earth, the Son of God raises his to gesture beyond the earthly realm and upward to the space above the bishop who kneels in the foreground.

The mirrored action of Christ’s and ‘the devil’s’ opposing hands signals the moral opposition between them. Similarly, their stance and posture produce both visual and narrative tension. Luther’s left leg awkwardly crosses his body as it moves toward the Son of God, drawing attention to his monstrous talons and curling tail. Christ steps toward Luther, drawing attention to his bare left foot. His bent right leg leads our eyes downward to the man of the church whose red robes visually and symbolically connect him to Christ.

Christ’s delicate balancing act heightens the most dramatic moment in this narrative of individual choice. Of course, Christ’s response to the Devil would have been well known to viewers of this altarpiece, but their own responses to temptation would have been less certain. Crucially, the beholder’s visual communion with Christ is arbitrated through the bishop in the foreground, who is placed between us and the Saviour. This compositional strategy echoes the role of the bishop during the sacrament of Eucharistic Mass, privileging and celebrating the mediating role of the church in the salvation of the soul.

References

Tümmers, Horst-Johs. 1964. Die Altarbilder des Älteren Bartolomäus Bruyn: Mit Einem Kritischen Katalog (Cologne: Greven Verlag)

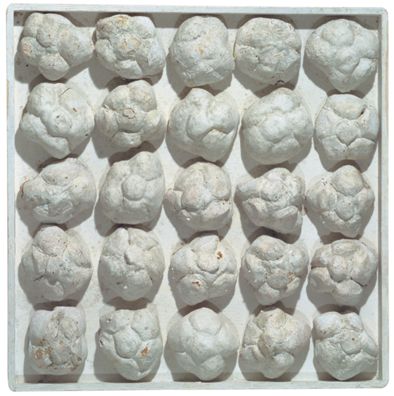

Piero Manzoni

Achrome with Bread Rolls, 1962, Kaolin, bread rolls on panel; © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome; Photo: © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images

By Bread Alone

Commentary by Carla Benzan

Unlike Christ, who refused to transform stone into bread (Matthew 4:4), Piero Manzoni decisively transformed bread into stone.

His 1961 work Achrome with Bread Rolls is formed of a tightly-packed grid of bread rolls which, when hung on a wall, seems as monumental as a marble frieze. Manzoni covered each roll in a slurry of kaolin, a naturally white clay, and let them harden before affixing them to a white painted panel. The pure whiteness of the undulating surface heightens the relief. Irregular knotted forms nestle side by side, pulling the eye along the uniform rows and between the round forms, down to shadows cast on the flat panel surface.

Manzoni produced a number of Achromes during his short career, each composed of natural or artificial materials chosen to create highly tactile surfaces. Evacuated of colour, clay-soaked bread, canvas dipped in gesso, bleached cotton balls, and raw fibreglass deny the representational or expressive aims of perspectival figurative painting. Meaning in these works is not about representation but about an evocation of the physical presence of the everyday object that engages the body as much as the eyes.

In this respect, Manzoni also challenges the visual abstraction of the Modernist monochrome through his celebration of the material world. Smell, touch, and taste are activated by the bread rolls, which are ubiquitous on Italian tables. Viewers recall piles of the familiar knotted buns stuffed with paper-thin swathes of mortadella, or pulled apart to soak up pools of tomato sauce from a plate of pasta.

And yet Manzoni frustrates the appetite. Instead of a soft, floury surface, viewers are confronted with a smooth hardened shell: cold liquid clay absorbed into the substance of the bread and dried to an inedible stone-like object. Eucharistic transformation of bread into the body of Christ is upended here: bread is transformed into Art.

But if Manzoni plays the role of the provoking heretic and omnipotent god-figure in this work, his devilry deals in the frustration of desire, rather than its satisfaction.

References

Mansoor. Jaleh. 2001. ‘We Want to Organise Disintegration’, October 95: 28–53

Jean de Wespin and Michele Prestinari [Sculptures, attrib.]; Melchiorre d'Enrico [frescoes, attrib.; possibly with Tanzio da Varallo and Domenico Alfano di Perugia]

The Temptation of Christ (Chapel 13), c.1570–1600, Polychromed terracotta, fresco, various materials, The Sacro Monte di Varallo, Varallo Sesia, Italy; Photo: © Bill Matthews

Up On The Mountain

Commentary by Carla Benzan

Christ’s first temptation is brought dramatically to life inside a pilgrimage chapel at the Sacro Monte di Varallo. The Sacro Monte (or Holy Mountain) is a unique pilgrimage site perched on a rocky bluff above the town of Varallo at the base of the Italian Alps.

Originally founded in 1491 as a spatial replica of pilgrimage shrines in the Holy Land, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it came to comprise forty-five chapels narrating different episodes from the gospels. Early modern pilgrims knelt at carved wooden partitions to peer through openings and meditate on sculpted and painted representations of Christ’s life. The painted backgrounds merge almost seamlessly with the three-dimensional sculpture to create a consistent and dramatic sense of space. Brightly painted lifesize sculptures seem to emerge from the perspectival frescos that cover the walls, floor, and ceiling of the architectural interiors.

Located near the rear wall of this barrel-vaulted chapel, the sculpted figure of the devil cradles a stone in his outstretched left palm. His other hand is raised in invitation as he turns to face the Son of God, who lifts his opposing hand in rebuke. The devil’s muted brown and green robes visually connect him to the painted wilderness behind him. A clear moral opposition between the figures is suggested by the contrast between these drab robes of the devil’s and the brightly-hued red and blue robes worn by Christ (symbolising his incarnation and divinity respectively). Christ is also distinguished from the jostling swarm of beasts represented in the rocky wilderness of the foreground: snarling, pacing, suckling their young, and devouring prey.

Behind the sculptures, and painted on the chapel walls, Christ and the devil are depicted in conversation in roughly the same scale as the sculptures. Standing closely together, Christ looks away from Satan, suggesting his rejection of the second and third temptations. These are represented further in the distance within a jewel-toned, atmospheric landscape. The Edenic vista connects the scene to the alpine terrain outside the chapel, contrasting with—and perhaps tempering—the ominous natural world that is represented in three dimensions in the foreground.

References

Göttler, Christine. 2013. ‘The Temptation of the Senses at the Sacro Monte di Varallo’, in Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Wietse de Boer and Christine Göttler (Leiden: Brill), pp. 393–445

Bartholomäus Bruyn the Elder and workshop :

The Temptations of Christ, 1547 , Oil on canvas

Piero Manzoni :

Achrome with Bread Rolls, 1962 , Kaolin, bread rolls on panel

Jean de Wespin and Michele Prestinari [Sculptures, attrib.]; Melchiorre d'Enrico [frescoes, attrib.; possibly with Tanzio da Varallo and Domenico Alfano di Perugia] :

The Temptation of Christ (Chapel 13), c.1570–1600 , Polychromed terracotta, fresco, various materials

Led By the Spirit

Comparative commentary by Carla Benzan

Hungry, exhausted, and exposed, Christ’s humanity is placed front and centre in the story of his Temptation.

The incarnation binds Christ to the fallen, material world. Through his own embodiment Christ offers a means to move toward salvation and ultimately to overcome the vulnerabilities of the bodily state. After all, when Christ refuses to turn the stone into bread he highlights spiritual sustenance over human appetites: ‘It is written, “One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God”’ (Matthew 4:4 NRSV).

Drawing on his skills as a portrait painter for the Catholic elite in Cologne, Bartholomäus Bruyn conjures up the uncanny likeness of the recently-deceased Martin Luther. The painting visualizes the threat of Protestantism in a Catholic city that was surrounded on all sides by reform movements. The clear hierarchical composition attempts to mitigate this danger. It transports the viewer from the earthly realm to the divine along a vertical axis whose entry point is a representative of the church. This patron kneels at the margins of an untamed natural space that offers visual pleasure as the gaze moves to the vibrant landscape, then to the city’s temple, and eventually to a towering mountainous spire of rock. Barely visible behind Luther, an elephant and grazing camel (frequent features of paintings of paradise) connect this lush wilderness to the garden of Eden prior to humankind’s fall.

Celebrating the natural world alongside Christ’s transcendence of it, the red robes of the ecclesiastical patron and of Christ direct the viewer’s gaze upward to where the two other temptations are depicted: the second temptation on the pinnacle of the temple is visible in the distant city on the right, and the rocky summit where the devil departs and Christ is attended by angels juts up high above the entire vista.

At the Sacro Monte in Varallo, the temptations are similarly linked with ascetic retreat in a natural environment, but the setting for the first temptation is distinctly hostile, while the later episodes take place in a distant idyllic landscape. The natural world is prominently represented by the diverse animals that congregate in the foreground and interrupt pilgrims’ views of the biblical subject as they contemplate the work. Exotic as well as local species include a lion tearing into the flesh of a deer, a wild dog with suckling pups, a bear, cheetah, and porcupine, and a pure white crane. The representation of nature certainly appealed to the lived experience of pilgrims who had travelled to the alpine location. At a threshold between the Catholic Italian states and Protestant Switzerland, the Sacro Monte was founded in a mountainous area long-associated with witchcraft and heresy.

And yet the natural world does not only connote moral peril. Milanese ecclesiasts like Archbishop Federico Borromeo advocated private meditation on images that assembled impossible scenes of nature’s diversity (Jones 1988). After all, it was a divine imperative that led Christ to make his retreat: ‘Jesus, full of the Holy Spirit, returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit in the wilderness’ (Luke 4:1 NRSV). Pilgrims to the Sacro Monte were invited to travel to this pilgrimage destination in order to expiate their sin and—like Christ—to reaffirm their faith.

Five centuries later in Milan, Piero Manzoni would reject orthodoxy of any kind, whether religious, political, or artistic. The transformation of twenty-five factory-produced bread rolls reconfigures the material and psychological realities of everyday life as American-style capitalism was imported into postwar Italy (Silk 1993). No perspectival depth or virtuosic effects coerce or connote. Colour is rejected in favour of a materially-dense but pictorially vacant surface emptied of the artist’s hand. Standing before Achrome with Bread Rolls, newly-liberated Italians confronted their own growing faith in the commodity object. With a profoundly agnostic attitude, Manzoni challenged the status of the commodity as much as the moral certitudes of Catholic dogmatism.

The three artworks in this exhibition foreground the physicality of the world and of images. Like Christ’s incarnate body, visual images can mobilize religious reflection and lead the viewer from the mundane to the spiritual. Bruyn’s detailed application of oil paint creates convincing visual effects of physical presence through the vibrant colouring, subtle shadows, and hazy light associated with Netherlandish art. At the Sacro Monte the life-size polychromed sculptures seem to emerge out of frescoed walls with an uncannily lifelike presence. The unsettling physicality of real bread dipped in clay in Piero Manzoni’s Achrome with Bread Rolls celebrates material presence over representational effects. By implicating their viewers in a scene of palpable realism that tests the boundary between life and art, each of these artists heightens the psychological drama of Christ’s confrontation with a series of individual choices about his own physical existence and his faith in the divine.

References

Jones, Pamela. 1988. ‘Federico Borromeo as a Patron of Landscapes and Still Lifes: Christian Optimism in Italy ca. 1600’, The Art Bulletin 70.2: 266–72

Silk, Gerhard. 1993. ‘Myths and Meanings in Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’Artista’, Art Journal 52.3: 65–75

Commentaries by Carla Benzan