1 Kings 17:8–24

The Widow of Zarephath

Works of art by Leandro Bassano, Unknown artist and Unknown French or Netherlandish Artist

Leandro Bassano

Portrait of a Widow at her Devotions, First quarter of 17th century, Oil on canvas, 105 x 89 cm, Private Collection; ART Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

From Cradle to Grave

Commentary by Barbara Crostini

That the widow in Leandro Bassano’s portrait is praying is indicated by the rosary beads draped across her hand and by the barely visible prie-dieu on which two silver candle stands are placed. A painting hangs above it—a birth scene, perhaps a replication of one of Bassano’s own paintings of the Birth of the Virgin. But rather than squarely facing this painting, the woman kneels at an angle to it, gesturing in its direction with her left hand while half-turned towards us.

A continuity between the subject of the painting and the painting-within-the-painting is created by the shiny object painted as though perched on the frame of the latter. It is a two-handled copper jug for water, at once a practical item in the context of a birth and something evocative of a sacred vessel, such as a cruet—like the candle holders, both useful and devotional. The white details of the woman’s scarf, handkerchief, and cuffs are also echoed by the details within the painted room: the women’s veils, scarves, towels, and the sheets appropriate to a bedroom. There is a multivalent quality to the birth scene too. Is it sacred or secular? Was the aged widow involved in that birth? Was she perhaps the naked baby held over the bath by the midwife, or the mother who is still lying on the bed? Is she showing us, and with her upturned palm almost caressing, an heirloom hanging in her noble home?

This solitary widow clad in black, like the widow of Zarephath with her dead child, sums up the wisdom of women. Her outstretched hands are expressive of many unspoken words. One, with open palm, displays a solid gold ring that connects her to a longer history of family and affection. The other, turned downwards, shows darker, more hardened skin marked by the experience of providing for others, sharing the altruistic impulse of the widow of Zarephath and Proverbs’ Woman of Valour, whose hands ‘are stretched out to the needy’ (Proverbs 31:20; Midrash Eshet Hayil, Batei Midrashot, vol. 2).

In this pose, she exudes an air of readiness for whatever life brings. She contemplates at once birth and death, light and darkness, past and future generations, absorbed in the dark mysteries of life to which she has gained privileged access.

Unknown artist

Resurrection of the widow of Zarephath's son by the prophet Elijah, from Dura Europas Synagogue, Completed 244 CE, Wall painting, National Museum of Damascus; The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

From Mourning to Joy

Commentary by Barbara Crostini

Wall paintings at the synagogue of Dura Europos, considered the earliest extant Jewish pictorial narratives, resist being interpreted against the biblical text. Scholars who have tried to press this image against the written narrative have been disappointed with the results.

Thus, Herbert Kessler and Kurt Weitzman lament that the artist ‘sacrifice[ed] a good deal of iconographic clarity’ by disregarding key elements of the biblical story for the sake of symmetry (Weitzmann and Kessler 1990: 108). They judged the panel to be a poor likeness of the text. By contrast, Carl Kraeling appreciated the artist’s synthesis and the linear movement from left to right that conveys the story ‘with the utmost clarity and simplicity’ (Kraeling 1956: 143). These divergent views demonstrate that the image is not simply text-derived, but transformed through interpretative mediation into a visual message.

The visual synthesis in the painting in fact works by highlighting dialogic interaction between the widow and Elijah in three salient moments. On the left, the widow in black mourning robes and with bare chest lifts up the lifeless body of her naked child, complaining to Elijah and accusing him of his murder (1 Kings 17:18). At the centre, Elijah reclines on his bed holding the child up towards the hand of God, praying for his life to return (v.20). To the right, the happy mother has changed her garment to bright yellow and holds a rosy-cheeked baby on her hip, proclaiming Elijah as true prophet (v.24).

Each moment is captured through dramatic gesture that underscores emotional dialogue between the characters. Viewers familiar with the story, read out or enacted in dialogue form, would read the panel like a tableau vivant, associating words with the images. The widow’s dramatic request and her joyful proclamation frame the prophet’s miracle and take precedence over his centre-stage posture. As a petitioning mother (Fein 2013), it is she who conveys the urgency of this story of hope in the face of death.

References

Crostini, Barbara. Forthcoming. ‘Performing the Bible at Dura: A Panel of Elijah and the Widow of Sarepta as tableau vivant’, in Performance in Late Antiquity and Byzantium, ed. by Niki Tsironi (Princeton: Center for Hellenic Studies)

______. 2023. ‘Empowering Breasts: Women, Widows and Prophetesses with Child’, in Motherhood and Breastfeeding in Late Antiquity and Byzantium, ed. by Aspasia Skouroumouni and Stavroula Constantinou (London: Taylor & Francis)

Fein, Sarah. 2013. ‘Prayer, Petition, and Even Prophecy: The Widow of Zarephath in Word and Image’, The Graduate Journal of Harvard Divinity School, available at https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/hdsjournal/book/prayer-petition-and-even-prophecy

Kraeling, Carl H. 1956. The Excavations at Dura-Europos Conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters: Final Report 8, Part 1: The Synagogue, ed. by A.R. Bellinger et al. (New Haven: Yale University Press), 143–46

Weitzmann, Kurt and Herbert L. Kessler. 1990. The Frescoes of the Dura Synagogue and Christian Art, Dumbarton Oaks Studies, 28 (Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks)

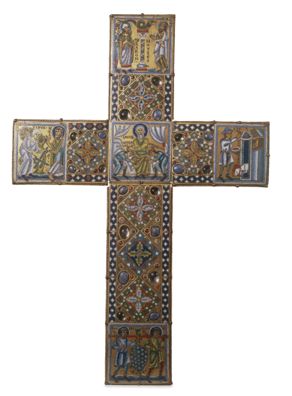

Unknown French or Netherlandish Artist

The Bouvier Altar Cross, c.1160–70, Enamel with semi-precious stones, 374 x 256 mm (overall), The British Museum, London; 1856,0718.1, ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

From Death to Life

Commentary by Barbara Crostini

This twelfth-century enamel cross assembles a variety of what are considered standard typological images of the crucifixion. The panels visually play with the shape of the cross, both in their geometrical, jewelled portions and in their iconographies. On the vertical shaft, the column and the horizontally winding serpent between Moses and Aaron (Numbers 21:4–9), the arms of Jacob crossed in blessing his symmetrically arranged grandsons Ephraim and Manasseh (Genesis 48), and the huge bunch of grapes dangling from the pole (Numbers 13), visually recall cross shapes. On the horizontal beam, a Hebrew man uses the blood of a lamb to mark the Tau on his house in Egypt (Exodus 12) and the Widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17:12) picks up firewood in such a way that two sticks form the shape of the cross. In this game of associations that engenders meaning, a whole tradition is gathered together in the shape of the cross.

The widow of Zarephath is the only woman in the composition. The Latin inscriptions identify the figures as VIDUA (‘widow’) and HELYAS (‘Elijah’). Vidua literally means ‘empty’ in Latin. Like Christ, this nameless woman empties herself as she stoops to gather wood, in an inclined pose that Adriana Cavarero stigmatizes as quintessentially motherly: ‘“Mother” … is thus above all the name for an inclination toward the other’ (Cavarero 2016: 104).

At the same time, her oblique body counteracts the movement of the living tree behind her whose crown bends backwards and creates yet another cruciform intersection. Its green foliage contrasts with the dead wood she holds up and the two types of wood, living and dried, hint at the promise of resurrection, of life after death.

Despite her marginal position on the side of the cross and her generic designation undeserving of a proper name, this widow is not subordinate to the prophet: she too is an agent of salvation. Within the square panel, she has pride of place, with Elijah seemingly having begun to walk out of the frame but now turning back in response to her with a gesture of blessing that visually echoes and extends Jacob’s blessing of Ephraim. Like Jacob, Elijah passes on to the widow the task of carrying forward God’s plan. The story of salvation continues in the humble, prophetic self-giving of this nameless woman.

References

Baert, Barbara. 2004. A Heritage of Holy Wood: The Legend of the True Cross in Text and Image (Leiden: Brill), pp. 107–11

Cavarero, Adriana. 2016. Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude (Stanford: Stanford University Press)

Leandro Bassano :

Portrait of a Widow at her Devotions, First quarter of 17th century , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

Resurrection of the widow of Zarephath's son by the prophet Elijah, from Dura Europas Synagogue, Completed 244 CE , Wall painting

Unknown French or Netherlandish Artist :

The Bouvier Altar Cross, c.1160–70 , Enamel with semi-precious stones

Widowhood, Want, and Wisdom

Comparative commentary by Barbara Crostini

As we read this chapter in the Bible, the spotlight rests on Elijah. The widow, meanwhile, remains nameless, though we learn that she has at least one child and that she lives in Zarephath, a coastal town in Phoenicia mid-way between Tyre and Sidon.

With the images in this exhibition, I read the encounter from her point of view, a woman’s and an outsider’s, foregrounding her experience of man-less motherhood to which Elijah added the extreme hardship of famine. Elijah lives the contradiction of suffering from a drought he himself has created (1 Kings 17:1) but his divinely appointed encounter with this woman at the edge of death serves to move him to relent from his anger against the idolaters, together with whom he had condemned other innocent people to suffer. According to both Jewish midrash and the pseudo-Chrysostom, Elijah’s power was re-negotiated with God according to his human response to the widow’s grief (Kraeling 1956:145; Ginzburg 1909: 196f.; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 113a; Barone 2008).

The designation of ‘widow’ in the Graeco-Roman world in which the Dura Europos synagogue paintings were executed did not simply mean a woman whose husband had died, but rather picked out any woman living on her own (Maier 2020; Galpaz-Feller 2008). The unusual singleness of women with respect to male figures could include cases where the husband had left temporarily, on business, for war, or to jail, but also denote a father who had never acknowledged responsibility in the first place.

While the ring in Leandro Bassano’s widow portrait excludes these possible scenarios, that the Sareptian may have been a single mother can be contemplated in her referring to her child as her ‘sin’ (v.18). The emarginated status and stigma attached to single motherhood compounds her difficulties through the hardship of famine as well as her alien condition as a non-Israelite. When Jesus, after reading in the synagogue at Nazareth, mentions her as an example of prophetic openness, the inhabitants react strongly against him (Luke 4:26). Yet, it is her attachment to life that one admires more than Elijah’s superpowers, as the story unfolds from one miracle to the next. The enchanted world of the prophet only makes sense when anchored in the real emotional experiences of the widow.

The Bible confers dignity and protection to widows (e.g. Exodus 22:22; Deuteronomy 10:18; 24:19), who were vulnerable even when they were wealthy. But it also confirms their marginalization (together with profane women and harlots) since the High Priest could not marry women from these groups (Galpaz-Feller 2008: 235).

At Dura Europos, free women could benefit from the ‘law of the three children’ (ius trium liberorum; see Sommer 2016: 64–65; Boatwright 2021: 24) and take charge of administering their own possessions. The matronly lead of the fresco panel in the synagogue reflects such agency. As in some Syriac dialogues that were likely performed as para-liturgical entertainment, this widow appears as verbal and vocal—her voice heard through her painted gestures. Her depiction attests to an oral tradition through which hearers and spectators of the word of God were given an alternative point of entry to the fraught encounter between Elijah and the widow.

This tradition of churning biblical episodes into further significant narratives is attested by the use of the imagery of the widow’s encounter with Elijah on medieval enamel crosses as part of a larger discourse about the inheritance of salvation. The marginal status of this woman is reversed in such iconography, as her own prophetic powers are materialized by her holding the cross—a sign of salvation—or in her proclamation of Elijah as true prophet after the resurrection of her son (1 Kings 17:24).

French archaeologist Robert du Mesnil du Buisson pointed out a similarity between the pose of the widow of Zarephath holding her resurrected child in the Dura panel and Gothic statues of Mary. In contrast to images where virginity is foregrounded, the portrayal of womanhood through widows presents knowledge acquired from experience of the concrete life-events of death and of birth. Bassano’s Portrait of a Widow at her Devotions, with its muted tones and contrasts, introduces another comparison with Mary through the meta-reference to a painting that might be of the Birth of Mary, and through the Marian devotion of the rosary chaplet which this anonymous woman holds in her hand. The loneliness of her stance contrasts with the crowded scene of birth where the bedroom is bustling with helpers and midwives. The pursed lips of this widow show how silence has descended on her as she meditates on women’s role in shouldering the key responsibilities of life.

References

Barone, Francesca Prometea. 2008. ‘The Image of the Prophet Elijah in Ps. Chrysostom. The Greek Homilies’, ARAM Periodical, 20: 111–24

Boatwright, Mary T. 2021. The Imperial Women of Rome: Power, Gender, Context (Oxford: OUP)

Brock, Sebastian Paul. 1989. ‘A Syriac Verse Homily on Elijah and the Widow of Sarepta’, Le Muséon, 102: 93–113

_______. 2020. ‘Elijah and the Widow of Sarepta: A Fragmentary Dialogue’, ARAM Periodical, 32: 1–7

Galpaz-Feller, Pnina. 2008. ‘The Widow in the Bible and in Ancient Egypt’, Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, 120.2: 231–53

Ginzburg, Louis. 1909. Legends of the Jews, vol. 4, trans. by Henrietta Szold (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America), available at https://www.sacred-texts.com/jud/loj/index.htm

Maier, Harry O. ‘The Entrepreneurial Widows of 1 Timothy’, in Patterns of Women’s Leadership in Early Christianity, ed. by Joan E. Taylor and Ilaria L.E. Ramelli (Oxford: OUP), pp. 59–73

Sommer, Michael. 2016. ‘Acculturation, Hybridity, Créolité: Mapping Cultural Diversity in Dura-Europos’, in Religion, Society and Culture at Dura-Europos, ed. by Ted Kaizer (Cambridge: CUP), pp. 57–67

Commentaries by Barbara Crostini