1 Peter 5

The Pastures of God’s Love

Jaime Huguet

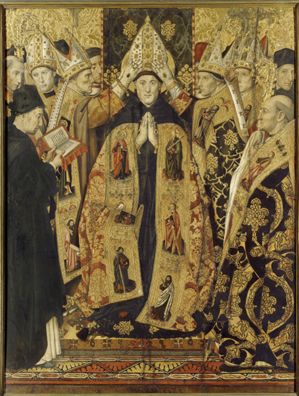

Consecration of St Augustine, c.1463–70s, Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood, 250 x 193 x 9.5 cm, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya; Purchased 1927, 024140-000, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Not Under Compulsion but Willingly

Commentary by Jane Williams

1 Peter tells the elders that they must agree to take care of God’s people, and that they must see this as a calling from God, not as an office carrying prestige or financial reward. Their calling is not to be elevated above the flock, but to be given over to the flock’s well-being.

The gorgeous painted altarpiece of Augustine’s consecration as bishop of Hippo rather undermines that point. The fifteenth-century artist has depicted a contemporary (rather than fourth-century) consecration of great lavishness. The consecrating bishops and the bishop-to-be are wearing richly embroidered robes, and their mitres and gloves are jewelled. The ‘flock’ are conspicuous by their absence, unless represented by the face peering through at the far right of the picture; but even he is probably a portrait of a donor, rather than a symbol of the people to whom a bishop is called. Augustine’s face is serious, but there is no doubt that this is a man entering into a great office, with pomp and ceremony.

Augustine himself tells a different story. In a sermon, preached to his people after he had been their bishop for many years, Augustine describes how he was seized upon and ordained priest with no preparation and little opportunity to discern a calling. ‘A servant ought not to oppose his Lord’, Augustine writes, ruefully, very much in the spirit of 1 Peter 5:6: even bishops are humble ‘under the mighty hand of God’ (Ramsey 2007: 407).

He was bishop of Hippo for over thirty years, describing it as a task compelled by love—of God and of God’s people. As the ambitious young Augustine takes up this yoke as the servant of an obscure community at the edge of the Empire, as the intellectual turns his hand to the education of his people, as the contemplative takes on the management of a divided and unruly province, Augustine lives out an exegesis of 1 Peter 5.

References

Brown, Peter. 1967. Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (London: Faber and Faber)

Ramsey, Boniface (ed.). 2007. St Augustine: Essential Sermons, Sermon 355, trans. by Edmund Hill (New York: New City Press)

Unknown artist [Syria]

Good Shepherd, 3rd–4th century, Marble, 61 x 39.5 x 16.5 cm (sculpture only); 74.5 x 35 x 25 cm (sculpture with stone base), The British Museum, London; Donated by Lt-Col Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson, 1919,1213.1, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

‘Tend the Flock’

Commentary by Jane Williams

This third-century sculpture shares the imagery of 1 Peter 5:2, which reminds the elders of the Church to ‘tend the flock’. Such labour was no pastoral idyll; it could be back-breaking and dangerous. Although the stone’s natural reddish-orange veining adds life to the sculpture, it also—perhaps by coincidence rather than design—makes it seem stained, as though with sweat or even blood.

The shepherd is strong, however—carrying the weight of the large sheep with practised ease; the naturalistic folds of his tunic falling evenly. There is a peaceful familiarity between shepherd and sheep. The sheep sits securely on the shepherd’s shoulders, feeling the anchor of his hand, with no need to struggle against it.

Heavily worn over the centuries, the carving now seems to run shepherd and sheep into each other: it is hard to tell where the shepherd’s hair ends and the sheep’s coat begins. The appearance of symbiosis and interdependence between the two has been deepened by the blurring of time. Without the sheep, there is no employment for the shepherd, just as without the shepherd there is no nourishment and safety for the sheep. 1 Peter 5 is speaking to shepherds, not sheep, but the image reminds the elders of their own sense of purpose and their own need of the flock they have been called to tend.

The carved face of the shepherd is attractive, with large eyes and a benevolent expression. The sculpture was later refashioned as a fountain, and the opening made to channel water through the shepherd’s mouth now makes it appear that he is singing—as a shepherd might (perhaps to give reassurance to the sheep he is carrying, or perhaps to call the rest of the flock). The utilitarian alteration has, touchingly, emphasized a theological point: this is an image of the Good Shepherd, whose sheep know his voice (John 10:27).

While 1 Peter 5 calls Christian shepherds to care for their sheep, it reminds them that the shepherds are themselves also the flock. In this sculpture, the bishop is both sheep and shepherd. There is a ‘chief shepherd’ (v.4), who cares for the carers. They are carried by Christ, as they carry others; they risk all for the flock because all was risked for them.

El Greco

The Repentant St Peter, After 1605, Oil on canvas, 93.7 x 75.2 cm, The Phillips Collection; Acquired 1922, Album / Art Resource, NY

‘Humble Yourselves’

Commentary by Jane Williams

El Greco’s picture of Peter makes a connection between Peter’s repentant tears and his worthiness to carry the keys that hang beneath his wrist. Peter is to be entrusted with the fearful responsibility of loosing and binding primarily because he knows that he himself lives as a forgiven sinner. Peter’s eyes are magnified by the tears that fill them, his hands clasped together in the fervour of his repentance; his whole being is shaped by the forgiveness of the one who has entrusted those keys to him. Peter is not likely to rush to harsh judgements of others.

The Gospels describe Peter setting off, with typical self-confidence, to follow Jesus after his arrest, and to stay with him come what may (Matthew 26:35, 58; Mark 14:31, 54; Luke 22:33, 54). Yet within hours, Peter is denying any knowledge of Jesus at all (Matthew 26:69–75; Mark 14:66–72; Luke 22:54–62; John 18:15–27).

But the Synoptic Gospels also suggest that Peter was the only disciple there at the time. Perhaps, from among their circle, only he and Jesus knew the full import of what happened in his denial (Luke 22:61). When, after the resurrection, Jesus seeks out Peter in the moving scene depicted in John 21, the conversation is still only between Jesus and Peter. Yet it never occurs to Peter to keep this private: he knows that this is what makes it possible for him to be a shepherd of God’s flock; the discipline of humility is an essential part of his leadership.

The elders to whom 1 Peter 5 is addressed are not encouraged to dwell on their own merits: they are told to be humble, to trust in God’s care, to be disciplined and alert, to think more of the sufferings of others than of their own, and to keep everything in an eternal perspective. No light task unless, like Peter, they are deeply formed by their primary relationship with God. El Greco’s Peter has his eyes fixed on the only source of hope, and so he carries the keys to the gates of death and hell.

References

Haliburton, John. 1987. The Authority of a Bishop (London: SPCK)

Marias, Fernando. 2013. El Greco: Life and Work (London: Thames and Hudson)

John Paul II, Pope. 1995. ‘Ut Unum Sint: On Commitment to Ecumenism, 25 May 1995’, www.vatican.va [accessed 13 October 2020]

Jaime Huguet :

Consecration of St Augustine, c.1463–70s , Tempera, stucco reliefs, and gold leaf on wood

Unknown artist [Syria] :

Good Shepherd, 3rd–4th century , Marble

El Greco :

The Repentant St Peter, After 1605 , Oil on canvas

Leadership in Counterpoint

Comparative commentary by Jane Williams

1 Peter 5 is addressed to the ‘elders’ (presbyterous), and is full of sobering but hope-filled advice. The focus moves back and forth, from the daily life of the flock, always at the mercy of the ravenous beasts, to an eternal perspective, the pastures of God’s love, to which the elders are guiding their charges.

The three works chosen to interact with this chapter show aspects of the leadership that is being described. The third-century carving of the Good Shepherd from what is today Iraq picks up on one of the images that Jesus regularly applies to himself, directly and indirectly—perhaps most famously in the parable of the Good Shepherd (John 10). The carving exudes strength, peace, and even joy, in the easy relationship between shepherd and sheep; the sheep trusts the shepherd’s hold, and its confidence means that it does not struggle against the shepherd, but allows itself to be held securely with one hand. Even those of us who have never held a sheep can feel the weight of it on those strong shoulders, and can imagine the sense of satisfaction as sheep and shepherd co-operate.

Jaime Huguet’s painting of Augustine’s consecration, on the other hand, suggests how much the conditions under which Christian leadership is exercised have changed from what 1 Peter outlines. The artist seems to revel in the colours and shapes of the vestments, and the challenge of representing all the officiating bishops clustered around Augustine, who is now joining what is clearly an important and influential company. 1 Peter warns against entering into leadership for financial gain or for the love of power. But by Huguet’s time, power is an assumed part of the role of a bishop, and embroidery and jewels signal authority.

The kind of leader Huguet paints is wearing robes appropriate to one who is part of the hierarchical structures of society, whereas 1 Peter points the elders towards a metaphorical but eternal crown of glory. The reality of Augustine’s episcopal ministry was more like what 1 Peter enjoins than what Huguet’s altarpiece glorifies, but the painting serves as a warning counterpoint. It is salutary to think that the first audience for 1 Peter would have responded to the carving from Iraq instantly, seeing in it Jesus, the Good Shepherd. They would have fewer clues to help them interpret what was going on in the painting of Augustine’s consecration. The symbols of episcopal office that had become commonplace by Huguet’s day, and that remain obvious to us today, would have been puzzling to the elders, struggling to guard their threatened flock in a hostile society. But if the setting in which Christian authority is exercised changes, the theological challenge remains.

El Greco painted the Repentant Peter a number of times. He may have done this at least partly in the service of the Church’s PR, in a period in which regular confession was being promoted. Yet the painting throws light on some of 1 Peter’s sense of what leadership entails. The symbols of Peter’s power—the keys—look almost like a manacle. There is no sense that Peter is going to enjoy the exercise of this authority. Instead, what holds the eye is the glorious golden robe that is wrapped around Peter, covering up the coarser tunic beneath, and cushioning the heavy keys so that they do not bruise Peter as he walks. The robe is Peter’s richest treasure, which is his repentance; paradoxically, this glowing gold is a symbol of humility. This is what makes Peter the rock on which the Church is built.

1 Peter 5 speaks out of an understanding of leadership that is pastoral, self-sacrificial, and eschatological. The author numbers himself with the elders to whom he is writing, rather than claiming to be their superior. He cites as his dual credentials that he witnessed the sufferings of Christ and that he, like them, lives in expectation of the future glory (5:1). Between those two poles, Christian leadership grows, and the tension between them gives shape to the task. The flock need to know that the journey through suffering is leading to green pastures, and they can only know that if their leaders can point to the one who has already travelled that way: Jesus Christ.

References

Clowney, Edmund P. 1988. The Message of 1 Peter (Leicester: IVP)

Michaels, J. Ramsey. 1988. 1 Peter; Word Biblical Commentary 49 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson)

![Good Shepherd by Unknown artist [Syria]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0524_Unknown+artist_Good+Shepherd_ART570522_cropped.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Jane Williams