2 Peter 2

False Prophets and Fallen Angels

Francisco de Goya

Que pico de Oro! (What a golden beak!), from the series Los Caprichos, 1799, Etching and aquatint, 217 x 151 mm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; RP-P-1921-2074, Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Loud Boasts of Folly

Commentary by Sarah C. Schaefer

Among Francisco de Goya’s most enduring contributions to the history of art are his biting critiques of the hypocrisies of Spanish society. Intellectually formed in the midst of the European Enlightenment, Goya’s optimism about the possibilities for social and political progress diminished as the French Revolution devolved into tyranny and massacre. His infamous Los Caprichos (a series of eighty prints published in 1799) diagnoses the troubles that continued to plague the Spanish social order, including hereditary power, arranged marriage, and folkloric superstition.

Like many of the prints in this series, What a Golden Beak! (Que pico de Oro!) could be interpreted in several (potentially contradictory) ways. A group of grotesquely rendered figures crowd around a podium on which an owl is perched, beak open and one leg raised. At first glance, the expressions and gestures of the huddled figures suggest rapturous enthusiasm. However, one could just as easily interpret the closed eyes and half-open mouths as slumber brought on by boredom. Scholars have generally identified the occasion as an academic or medical lecture. A viewer might equally liken the posture of the owl before the huddled crowd to a minister pontificating before his congregation.

2 Peter 2 speaks urgently to the consequences of following false teachers and prophets. The final verses offer a litany of invective against those who utter ‘loud boasts of folly’, who offer freedom, but ‘themselves are slaves of corruption’ (2 Peter 2:18–20). Like Goya’s print (and many others in Los Caprichos), Peter’s letter likens the impulses of false prophets to the base actions of lower beings: they are ‘irrational animals, creatures of instinct, born to be caught and killed, reviling in matters of which they are ignorant’. They ‘will be destroyed in the same destruction’ as the base creatures they resemble (2 Peter 2:12).

The challenge of identifying those who deal in corruption and folly is at the core of Goya’s print, and its ambiguity is part of what makes the image so powerfully complex. Although Goya embraced the ideals of the Enlightenment, his works often suggest that blind adherence to pure reason may result in its own set of horrors.

References

Schulz, Andrew. 2005. Goya’s Caprichos: Aesthetics, Perception, and the Body (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 139–40

Andrea Commodi

Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1612–14, Oil on canvas, 170.69 x 182.88 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; 00123769, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Defiling Passion and Despising Authority

Commentary by Sarah C. Schaefer

Around 1616, Andrea Commodi secured a commission for the end wall fresco of the Cappella Paolina in the papal Quirinal Palace. Enraptured by the works of Michelangelo (and acquainted with the Buonarroti family), Commodi prepared a design that would rival the master’s Last Judgement. Although the fresco was ultimately abandoned, a number of studies remain, including two pen and ink drawings now in the British Museum, and this elaborate preparatory painting.

The subject Commodi chose represents both a significant connection to and also a departure from Michelangelo’s work, which itself was unorthodox. The Last Judgement incorporates both the damned and the saved (in adherence to iconographic tradition), but, importantly, the bodies of members of both groups are heroically muscular (as opposed to the emaciated forms of the damned one often finds in medieval tympana).

The fate of the angels who joined Satan’s rebellion is mentioned several times in the New Testament (see Revelation 12:7–9; Matthew 25:41; 1 Corinthians 6:3; Jude 1:6). They are only mentioned in passing here in 2 Peter 2:4. But the allusion is unusual in its lack of reference to Satan himself, as the agency of the rebel angels is generally conflated with that of their master. Although this painting represents only a fraction of the intended final work, the isolation of the angels from any narrative surrounding may perhaps be significant, seeming to have much in common with 2 Peter 2. The fallen angels maintain their heroic, idealized nude forms, much like the sinful people being dragged into the hellmouth at the lower right of Michelangelo’s fresco. The musculature of the angels’ bodies is made all the more palpable through their representation in grisaille, a painting technique that employs a monochromatic palette and enhances the sculptural qualities of the objects depicted. And, notably, Satan is not represented in this visual scheme—nor is there any divine figure doling out judgement. We are witness only to the writhing, contorted, despairing forms of those who followed the deceiver.

This underscores the consequences of succumbing to earthly desires, particularly those who, according to Peter, ‘indulge in the lust of defiling passion and despise authority’ (2 Peter 2:10).

Unknown, after Schacher

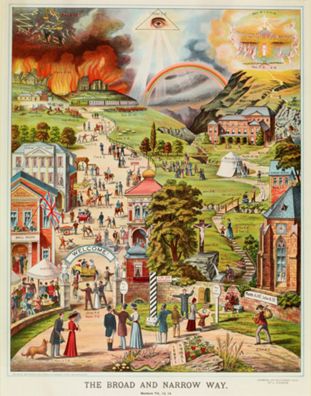

The Broad and Narrow Way; printed by Headly Brothers; published by Gawin Kirkham, 1883, Colour lithograph, 470 x 372 mm, The British Museum, London; 1999,0425.13, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Welcome to Perdition

Commentary by Sarah C. Schaefer

Although the immediate source of Gawin Kirkham’s The Broad and Narrow Way is Matthew’s account of the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 7:13–14), this print is a visual panoply of biblical exegesis on the subject of the proper route to salvation. Originally made in Germany, the preacher Kirkham had it reproduced with English text to accompany a sermon, and the picture found widespread appeal among Victorian evangelicals.

The print is indebted to the traditions of didactic and exegetical print culture that flourished in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries following the emergence of the Protestant Reformation, particularly in the Netherlands with publishers like Hieronymus Cock and Johannes Wierix. It offers didactic complexity through a profusion of narrative incidents accompanied by biblical passages. At the same time, there is clear, visual legibility in the stark division between the ‘broad’ and ‘narrow’ paths. The former, the more densely populated, abounds with sensual worldly pleasures. The latter is accessible only through an inconspicuous doorway, which leads to a more isolated and challenging journey. In both form and content, the print is likely to have been indebted to contemporaneous illustrations for John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, a seventeenth-century Christian allegory that was immensely popular in Victorian England.

The Petrine Epistles are specifically referred to several times in the print—for example, Peter’s description of false prophets as waterless springs (2 Peter 2:17) is visualized as an empty fountain just beyond the wide and welcoming entrance to the broad path. More important, however, is the extent to which the print dovetails with the overarching content, tone, and progression of 2 Peter, which is primarily aimed at providing guidance for righteous behaviour and the consequences of a life of sin.

The dating and authorship of the letter has long been subject to scrutiny, particularly considering its similarities to the letter of Jude and the stylistic departure from 1 Peter. Assuming that it was most likely to have been written within a century of Jesus’s death, 2 Peter speaks to the manner in which the Christian Church’s early adherents anticipated the certainty of divine judgement as interpreted through Old Testament prophecies and the words of Christ. The Kirkham print continues that tradition using the visual trappings of Victorian life.

References

Massing, Jean Michel. ‘The Broad and Narrow Way from German Pietists to English Open-Air Preachers’, Print Quarterly, 5.3: 258–67

Francisco de Goya :

Que pico de Oro! (What a golden beak!), from the series Los Caprichos, 1799 , Etching and aquatint

Andrea Commodi :

Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1612–14 , Oil on canvas

Unknown, after Schacher :

The Broad and Narrow Way; printed by Headly Brothers; published by Gawin Kirkham, 1883 , Colour lithograph

Paths of Ambiguity

Comparative commentary by Sarah C. Schaefer

The fiery rhetoric and vivid imagery of 2 Peter 2 continues the prophetic traditions found in the Old Testament. Announcing itself to be written on the occasion of the author’s impending death (2 Peter 1:13–15), the letter conjures up images of divine judgement, as a means of highlighting the proper paths of Christian life.

The dating and authorship of 2 Peter have been subject to continued debate—its content and style more akin to the Epistle of Jude than the first Petrine letter. It distils a number of themes conveyed in the Sermon on the Mount, particularly in setting forth clear delineations between truth and falsehood, morality and corruption (see Matthew 7:13–20). Moreover, the letter makes brief references to a number of motifs and events (false prophets, the fall of the rebel angels) that are more thoroughly expounded elsewhere in the Bible, in both the New and Old Testaments. Thus, although these subjects have frequently been subject to visual representation, 2 Peter is rarely the direct source.

However, as Gawin Kirkham’s The Broad and Narrow Way demonstrates, it is crucial to consider texts like this as part of a complex network of biblical exegesis. And although one could spend considerable time tracing the linkages in this network (and Kirkham’s print is certainly not exhaustive in its biblical sources), the broader message is clear: one path of life is more accessible and alluring, yet results in destruction and damnation; the other is winding and difficult, but has light and salvation as its ultimate reward. The apex of the image—the all-seeing eye of God enclosed in a radiant, triangular form—is in fact a reference to Peter’s first letter, which, although stylistically distinct from 2 Peter, is in this case thoroughly relevant: ‘For the eyes of the Lord are upon the righteous, and his ears are open to their prayer. But the face of the Lord is against those that do evil’ (1 Peter 3:12).

The urgency of following the path of righteousness is made palpable by the extent to which false paths can be cloaked in seductive words and alluring imagery. It is not difficult to imagine someone reading the words in the letter of Peter and wondering if this is itself the work of a false prophet or teacher. That the presumed author was Christ’s most trusted apostle and the ‘rock’ on which his Church was built (Matthew 16:18) might assuage those concerns.

The challenge of detecting false prophets and teachers owes as much to appearances as it does to the spoken or written word. The imprint of diabolical forces is not always physically manifest and readily perceivable to the attentive (let alone the passive) viewer. Andrea Commodi’s fallen angels remain powerfully masculine in their heroic nudity, perhaps embodying the desires of the flesh of which Peter warns. The golden-beaked owl in Francisco de Goya’s print conveys a contradictory set of symbolic resonances—historically, the owl could be interpreted as a sign of wisdom or folly, as vigilance or an omen of death. This is particularly powerful and disconcerting in the wake of the Enlightenment, when it was widely thought that adherence to reason over blind faith would lead to better circumstances for the masses. As Goya was well aware by the time he produced Los Caprichos (and as would become even more evident with the Napoleonic invasion of Spain), what appears to be the right path forward may very well lead to destruction and tyranny.

In many ways, the three images discussed here cohere with the dogmatic rhetoric of 2 Peter 2, which asserts a kind of Manichean worldview with respect to right and wrong, good and evil. However, Goya’s and Commodi’s images also underscore, in more or less subtle terms, the difficulties in discerning that boundary, which appears so clear in the Kirkham print.

The anxiety that Peter’s letter has undoubtedly evoked among adherents is made all the more crushing in his final assertion that those who initially followed the path of righteousness and strayed from it are ultimately in direr straits than those who never knew the true way.

Commentaries by Sarah C. Schaefer