Revelation 20:11–15

The Last Judgement

William Blake

A Vision of the Last Judgement, 1808, Pencil, pen, and watercolour on paper, 50.3 x 40 mm, Petworth House, Petworth, Sussex, UK; The Egremont Collection, 486270, Derrick E. Witty / National Trust Photo Library / Art Resource, NY

And the Truth Will Set You Free

Commentary by Judith Wolfe

This watercolour is an earlier version of a monumental Vision of the Last Judgement that William Blake painted in tempera and gold but that disappeared shortly after his death in 1827. The composition teems with the energy of a hundred figures, whose movements upwards (to the enthroned Christ’s right) and downwards (to Christ’s left) creates the impression of a single living shape: a human skull.

It is within this human skull that Blake imagines the Last Judgement to take place: not as the final act of history, directed by an external authority, but as an apocalyptic transformation of the mind. ‘If the spectator could enter into these images in his imagination’, he writes about the painting, ‘approaching them on the fiery chariot of his contemplative thought … then would he arise from the grave’ (Blake in Gilchrist 1863: 193).

The scene is not, like more traditional Last Judgements, intended as an image of what the world will, on the last day, turn out truly to be. Rather, it is intended to represent, and therefore to liberate, the creative energy of the imagination. The very fantasticalness of the iconography of the Last Judgement, which in more orthodox depictions is a potential embarrassment to faith, is here its lifeblood.

The Last Judgement, in Blake’s hands, does not fix the shape and meaning of things for all eternity, but on the contrary keeps them in an eternal dance. For the reader of Revelation, this artistic approach may jar with the text, which has a great decisiveness; but in setting our minds on fire with possibilities beyond those readily apparent around us, the painting also feeds into the work of that text by waking a desire for the overflowing joy promised in the chapter following it.

References

Gilchrist, Alexander (ed.). 1863. ‘A Vision of the Last Judgement’, in Life of William Blake, vol. 2 (London: Macmillan), pp. 185–202

Gislebertus

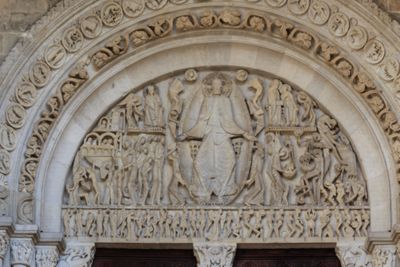

Last Judgement, 1130–45, Stone, West tympanum, Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, France; Hervé Lenain / Alamy Stock Photo

The Gates of the New Jerusalem

Commentary by Judith Wolfe

The Great West Doors of the Cathedral of Saint Lazarus of Autun in Burgundy are overshadowed by a relief carving of the Last Judgement. It is of a size so great that it requires a central compound pier and a double lintel to carry its weight.

Enthroned within a mandorla at the centre of the cosmos, the zodiac arrayed around him in the outer archivolts, Christ sits in judgement. To his right stands Peter, his enormous key slung over one shoulder. Its upper end seems almost like a grappling hook, giving him purchase on the heavenly space in which Mary blesses and intercedes. The souls of the saved, naked and small like children, cling to him and to an angel, as though waiting to be hoisted up to the arcaded structures of the New Jerusalem.

To Christ’s left, and below two seated Apostles, St Michael and the Devil are contending for the souls of sinners. Like those of Christ, Mary, and Peter, the pose of St Michael’s elegantly elongated body is full of gentle grace: two naked souls hiding in the folds of his garment, he cradles another soul in its scale as in a Moses basket, while demons pile into the balancing scale to weigh it down. A tangle of demons stuff the damned whom they have won into the mouth of hell.

The cathedral was a site of pilgrimage to the bones of a Lazarus thought to be the friend of Jesus, though in fact a Frenchman of the same name. The pilgrims arriving at its west portal joined the souls in stone awaiting judgement along the lintel, perhaps, like two of them, carrying pilgrim bags with the cross of Jerusalem or the seashell of Santiago de Compostela.

The tympanum above the door transformed their pilgrimage into the journey of their lives, culminating here in judgement and salvation, and in the great gates of the New Jerusalem in which they would find the bones of Lazarus, awaiting their second raising.

Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Last Judgement, 1536–41, Fresco, 13.7 m x 12 m, Sistine Chapel, Vatican City; Vatican Museums and Galleries, Vatican City / Artothek / Bridgeman Images

Apollo Be My Judge

Commentary by Judith Wolfe

Michelangelo’s Last Judgement takes place in a painted sky covering the altar wall of the Sistine chapel. Unlike the ceiling, which arguably occupies its own artistic world, the Last Judgement irrupts into the world of the worshippers, and concentrates their lives in a moment of decision. The onlookers are guided by the saints—St Lawrence, St Bartholomew, St Catherine—who, fixing their gaze on Christ, present the instruments of their martyrdom as tokens of their choice. It is their resolution, not Christ’s, which appears to be the site of decision-making in this judgement.

Christ, though clearly the centre of the fresco, is more gazed upon than gazing. He is not serene on his throne delivering judgement, but contorted and agitated, his arms raised in an ambiguous gesture that may either summon or repel, as it directs upwards and thrusts downwards. His mother huddles against him as she draws her veil around her face while crossing her arms over her chest—perhaps in prayer.

The worshippers are cast into the middle of this drama. The sky—this-worldly and full of clouds—seems to rise above the altar. The figures are so hyper-corporeal that the weight of the saved must be dragged upward and the angels are without wings. And although Christ is framed by an Apollonian sun, the figures are illusionistically illuminated from the left, that is, the northern side of the church, prompting us to ask: where will light come from at the sunset of our world?

The text of Revelation 20 describes a vision of the end of the world. Here, the artist has torn down the boundaries between that final judgement and the worshippers’ own time, and brought them face to face with Christ, their response to whom determines salvation or damnation. Here in this chapel, they are called to decision so that, unlike the damned in the fresco, they will not, at the end of time, have to confront the horror of having made their choice without realizing it.

William Blake :

A Vision of the Last Judgement, 1808 , Pencil, pen, and watercolour on paper

Gislebertus :

Last Judgement, 1130–45 , Stone

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

The Last Judgement, 1536–41 , Fresco

‘The Spirit and the Bride Say Come’

Comparative commentary by Judith Wolfe

Some biblical texts recount things that are in the writer’s past. Some envision things that are in the writer’s future but the reader’s past. Some tell stories or give instructions. But Revelation 20:11–15 recounts a vision of something that is yet to come, not only for the writer, but for every single reader of the text. It foretells a final judgement to be passed on the lives of the dead according to records of their deeds, and of a sovereign Book of Life.

This claim to be a literary account of a pictorial vision foretelling a universal future gives the text a complicated form and status, which inevitably shapes its artistic reception. Though Revelation 20:11–15 is a visionary text, it follows the Jewish apocalyptic style of presenting the vision not directly, but in the form of a reported experience: ‘Then I saw a great white throne…’ (v.11).

In drawing attention to its status as a seer’s secondary report of his vision, the text grants the artists who engage with it unusual power. Other biblical texts may press them into the role of illustrators or interpreters; this text, by contrast, raises them above itself. Representations of the Last Judgement, in being visual, can implicitly function as though they are the originals of the reported text.

This reversal of the roles of text and illustration has a radical effect not only on artists but also on their audiences. If an image assumes the role of the vision reported by the text of Revelation 20:11–15, then its onlooker assumes the role of the visionary who beholds it: he or she stands with Revelation’s seer, John of Patmos. Pictorial representation therefore heightens the dynamic that drives the book of Revelation itself: a visionary vortex designed to draw readers and viewers into its movement of terrible hope for the ‘desire of nations’—‘And the Spirit and the Bride say, “Come”. And let everyone who hears say, “Come”. … Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!’ (Revelation 22:17, 20 NRSV).

This affective intensity lends a performative dimension to any encounter with a picture of the Last Judgement. Artists throughout Christian history have given that dimension particular shape by the placement of their visual representations. In the Middle Ages, Last Judgements were most often found on tympana, that is, above the main doors of large churches and cathedrals (as at Autun). There, they marked the boundary between the ‘city of the world’ and the ‘city of God’, transforming the cathedral into a symbol of the heavenly Jerusalem. Later Last Judgements were sometimes placed on altar walls (as in the Sistine Chapel). Here, they impressed on the worshippers the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist as the promise and preparation of his parousia or second coming: a nourishment in whose strength they ‘shall see God’ when ‘at the last he will stand upon the earth’ (Job 19:25–26). In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Last Judgements were increasingly displayed in secular gallery spaces (as those painted by William Blake, or those of John Martin; Tate Gallery, T01927). Here, they intended to give new depth to the viewers’ ordinary experience.

In all these contexts, representations of the Last Judgement aim not at a self-sufficient aesthetic experience, but at an active re-orientation within the world towards the salvation they envision. By stepping through the cathedral doors, by eating and drinking, by awakening their imagination to the hidden depth of the world, onlookers are empowered to enact the decisions that their visual confrontation with the ‘great divorce’ between blessed and damned demands. By being in some sense more real than the world around them, the images make that world, and the choices of those who have seen them, more real in turn.

References

John Martin's Last Judgement: The Tate website https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/martin-the-last-judgement-t01927 [accessed 5 November 2019]

Commentaries by Judith Wolfe