2 Peter 3

Fire!

Works of art by John Martin, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi and Unknown artist, Tamil Nadu, South India

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

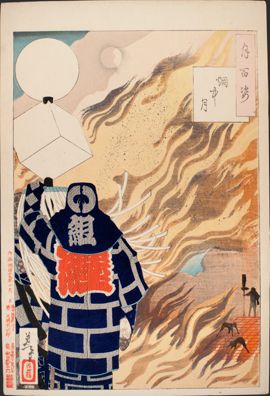

Moon and Smoke, 1886, Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, 364 x 244 mm, The Dayton Art Institute, Ohio; Museum purchase with funds provided by Jack Graef Jr., Linda Stein, Susan Shettler and their families in memory of Jack and Marilyn Graef, 2019.9.59, Courtesy of the Dayton Art Institute

Fire, Fire, Everywhere

Commentary by Peter Doebler

2 Peter 3 says the coming day of the Lord will destroy the heavens and earth with fire and goes on to describe it with visceral terminology including: ‘with a loud noise’ (rhoizēdon), ‘will be dissolved’ (lythēsetai, lythēsontai), ‘set ablaze’ (pyroumenoi), and ‘will melt’(tēketai) (2 Peter 3:10, 12 NRSV).

Such an overwhelming flame is condensed in Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s woodblock print Moon and Smoke from the series One Hundred Aspects of the Moon. Since Japanese houses were traditionally built with wood, towns were vulnerable to fire, especially densely populated ones like Edo (modern-day Tokyo). The firefighter seen from behind in the left foreground holds aloft a standard that helps identify the squad fighting the fire as there could be a reward if property was preserved.

The intensity of the fire described in 2 Peter 3 is evoked in this work by the superimposed use of multiple woodblocks, inked with different colours. They render the flames in a fluorescent tapestry of yellows, oranges, and greys. Powdered shells and glue sprinkled on the surface of the paper add a three-dimensional effect suggesting embers leaping into the air.

There is a cosmic aspect to the fiery destruction in the epistle. Not only are ‘the earth and everything that is done on it’ burned up (2 Peter 3:10) but the fire reaches to the heavens (v.12). Such an engulfing of both heaven and earth may also be seen in Yoshitoshi’s print. Its right side is dominated by a myriad of diagonal lines forming flames that rise up, leading the eye from the skeletal remains of a roof in the lower right to where the moon is shrouded in smoke at the top of the print, just left of centre.

Reading this detail alongside 2 Peter 3, we may see a foreshadowing of the unthinkable: that even the heavenly bodies will not be immune from the all-consuming fire of the day of the Lord.

John Martin

The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1852, Oil on canvas, 136.3 x 212.3 cm, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne; TWCMS: C6975, © Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums / Bridgeman Images

Inferno

Commentary by Peter Doebler

The centre of John Martin’s Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is a swirling inferno. Equal parts fire, cyclone, and tsunami, it appears to melt and mix all the matter it engulfs. Even the fire itself seems to dissolve as the paint is reduced to abstract, blended smears that seem almost to drip down the canvas. The apocalyptic intensity of the scene gives palpable form to the stark description of the coming day of the Lord in 2 Peter 3:10–13.

The pairing of 2 Peter 3 with an image of Sodom and Gomorrah is fitting, for the biblical prototype of fiery destruction on a local level is the account of the cities doomed in Genesis 19. Earlier in the epistle, the author cites examples of past divine judgement, including just these cities (2 Peter 2:4–10). In particular, their story has sharp relevance to the message the author addresses to his Jewish Christian community: to remain faithful and pure like Lot against those who mislead and indulge in sensual excess.

Martin’s epic composition is punctuated by a diagonal flash of lightning that ends at the figure of Lot’s wife, an example of one who, contrary to 2 Peter’s exhortations (2 Peter 1:10; 2:1, 20–22; 3:14, 17), did not persevere in the faith. The figure marks a transition between two realms: the background (those marked for destruction) and the foreground (those who, like Lot and his daughters, escape through the compassion and patience of God; 2 Peter 3:7–9).

Ironically, Martin gives the viewer the perspective Lot and his family were prohibited from taking—looking back on the cataclysm. For when one looks at the painting, the cluster of survivors on the right are merely a steppingstone that leads the eye to the mesmerizing glow of death.

Unknown artist, Tamil Nadu, South India

Nataraja, Shiva as the Lord of Dance, 11th century, Bronze, 113 x 102 x 30 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art; Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1930.331, Open access courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art

Ring of Fire

Commentary by Peter Doebler

One of the distinctive images in the history of Indian art is that of Shiva as Nataraja, Lord of the Dance. This sculpted version depicts Shiva as the creator, sustainer, and destroyer of the world. In one hand he holds a drum, symbolic of creation; in the other is a tongue of fire, symbolic of destruction. He dances within a ring of fire, embodying the Hindu conception of the world as a constant cycle of creation and destruction.

While it might seem unusual to use the depiction of a Hindu god to illuminate a Christian text, making a creative connection may help the traditions converse across their differences. The idea of fire-as-destruction, so prominent in Hinduism, is also central to the vision of the coming day of the Lord in 2 Peter 3: fire that dissolves everything, preparing the way for the new heavens and earth (vv.10–13). Further, the circular form of the sculpture seems an apt visual counterpart to 2 Peter’s references to cycles of fire and water across time (2:4–10; 3:5–7), which are unusual aspects of this text in New Testament terms.

The dancing Shiva in his creative aspects also has affinities with the benevolent features of divine activity mentioned in the epistle: by the word of God the heavens and earth came into being and are sustained (2 Peter 3:5–7). Shiva’s right hand gestures the mudra of peace. The gesture, along with the figure’s serene countenance, recalls the compassion and patience of God mentioned in verses 9 and 15.

Throughout 2 Peter, the author makes a case for why the Christian should endure and be pure, avoiding false teachers who are notable for wallowing in sensual lusts (3:3). A subtle detail of the Shiva sculpture is the demon he dances upon, symbolic of ignorance and illusion, the things that lock humans in the karmic cycle of death and rebirth. The false teachers in 2 Peter are comparably captive to their own misguided thinking. Both the figure of Shiva and the words of 2 Peter, in different ways and in very different religious traditions, exhort believers to overcome false attachments, place their hope in true authority, and escape the coming fire.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi :

Moon and Smoke, 1886 , Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper

John Martin :

The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1852 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, Tamil Nadu, South India :

Nataraja, Shiva as the Lord of Dance, 11th century , Bronze

Dissolved

Comparative commentary by Peter Doebler

When a fire starts, the first spark is like an epiphany: it appears, as if from nothing, and soon becomes everything.

The day of the Lord in 2 Peter 3 appears in the same way, like an unannounced thief (v.10; 1 Thessalonians 5:2; cf. Revelation 3:3; 16:15; Matthew 24:43). This sudden interruption of the cycle of life is exemplified in each of the artworks considered here; in particular, in the way circles—suggesting wholeness and stability—are interrupted by diagonal lines—suggesting imbalance. The circle of life around Shiva is broken by the slanting arm and leg, as if to initiate destruction; the still circles of the moon and fireman’s standard in the Tsukioka Yoshitoshi print are accosted by the diagonals of fire that engulf the wooden buildings of Edo; the slant of lightning cuts in front of the ball of fire obliterating Sodom and Gomorrah.

Restricted colour palettes also play a role, especially in John Martin’s painting and Yoshitoshi’s print. In these, it is the yellows, oranges, and greys of fire that dominate the image. They lack the vibrant, diverse colours often associated with flourishing life; rather, the muted range of these works suggests the uniform destruction of the day of the Lord’s fire.

At the same time, while all the artworks depict fire, the flames are styled differently in each. Thus each can evoke a different facet of the apocalyptic fire in 2 Peter 3:10–12: loud noise, intense heat, and all-encompassing scope. In Yoshitoshi’s print, the varied colours of the flames are layered one upon the other like orchestrated sounds that create the cacophony of final judgement. Martin’s image makes use of a feature of oil paint—that it can easily be manipulated and blended—to form a viscous crucible that suggests the emanation of intense heat. In the Shiva sculpture, each flame stands alone, as though individual emissaries assigned to burn up each and every thing on the earth and beyond. Together, they can communicate the sonic, haptic, and all-inclusive nature of the final fire on the day of the Lord.

Finally, the scale of each of these three artworks can suggest three different perspectives from which to view the prophetic vision of 2 Peter 3. Yoshitoshi’s print is on an intimate scale—a sheet of paper a little larger than a notebook, easy to hold. The main figure in the print looms large in the foreground with his back to us. He becomes almost a surrogate for the beholder, so that we feel as though we are the fireman on the front lines, dangerously close to the destruction. Martin’s panoramic landscape, by contrast, fills the field of vision, overwhelming the viewer. The huge scale of the canvas accentuates the small size of the figures of Lot, his wife, and his daughters. This creates an almost vertiginous perspective. In the case of the Shiva sculpture, an almost human scale is at work—and it is the only one of the three artworks where the human face is visible and facing the viewer, inviting an interpersonal encounter. This is appropriate considering the ritual function of the sculpture, meant for processing before devotees.

In their three different viewing perspectives amid scenes of fiery destruction, the artworks pose the same question that sits at the heart of 2 Peter 3’s vision of cosmic fire, sandwiched between verses 10 and 12: if all things will dissolve in this way, what sort of person should you be?

Commentaries by Peter Doebler