Matthew 12:1–8; Mark 2:23–28; Luke 6:1–5

Plucking Grain on the Sabbath

Ben Shahn

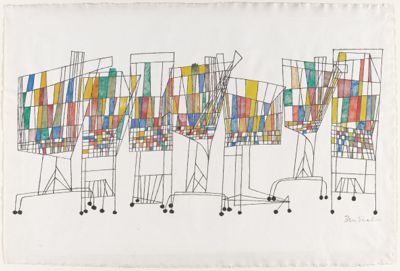

Supermarket No. 1, 1957, Colour screenprint, 676.3 x 1016 mm, Minneapolis Institute of Art; Gift of Mrs. Edith Halpert, 1960, P.12,802, © 2021 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Photo: © Minneapolis Institute of Arts, MN, USA / Bridgeman Images

Affirmation and Authority

Commentary by Simon Ravenscroft

Our Synoptic Gospel passages each end with Jesus saying that the Son of Man is ‘lord of the Sabbath’. This statement of his own authority rests on Jesus’s demonstration, by appeal to Scripture and the deeper principles of the Torah, that his interpretation of Sabbath law is authoritative. In him the Law is being fulfilled, not laid aside.

The dispute is followed in all three Gospels by a similar one, where the Pharisees again accuse Jesus of breaching the Sabbath, this time by an act of healing. Jesus’s response suggests that the Sabbath is faithfully kept by doing good in the service of life (Mark 3:4). Across both passages, Jesus’s authority in handling the Law finds expression in words and actions that affirm and restore.

Ben Shahn’s Supermarket is a quintessential image of American consumerism, even appearing on the cover of a book on the subject (Gagnier 2000). Shahn was known for his leftist politics, and it is tempting to read the work as a critique of life under capitalism, perhaps contrasting its angular, jagged shapes—evoking the metallic artificiality or even violence of industrial mass production—with the natural, softly sweeping lines of the pastoral Wheat Field, discussed elsewhere in this exhibition. Yet Shahn himself linked Supermarket with Wheat Field and two other prints, Silent Music and TV Antennae, as ‘abiding symbols of American daily life, to be celebrated and brought into awareness’ (McNulty & Shahn 1967: 114). He also gave a copy as a gift to the owner of a local supermarket that had suffered a fire.

Perhaps therefore the artwork is better understood as a simple affirmation of people’s ordinary lives in ambivalent social and economic contexts. Considered thus, its patterning of shapes and colours evoke a sense of lightheartedness, whimsy, even humour rather than harshness. This affirmative mood is closer to that which characterizes the authority of Jesus’s teaching in the Gospels—for example, in many of his parables (Bailey 1983)—and serves to illuminate it.

References

Bailey, Kenneth E. 1983. Poet and Peasant and Through Peasant Eyes: A Literary-Cultural Approach to the Parables in Luke (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Gagnier, Regenia. 2000. The Insatiability of Human Wants: Economics and Aesthetics in Market Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Kulju, Jen. 2017. 'Ben Shahn Exhibition Benefits JMU Students, Madison Art Collection, James Madison University', https://www.jmu.edu/news/arts/2017/04-03-ben-shahn-exhibition.shtml, [accessed October 21 2020]

McNulty, Kneeland and Ben Shahn. 1967. The Collected Prints of Ben Shahn (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Ben Shahn

Handball, 1939, Gouache on paper mounted on board, 578 x 794 mm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, 28.1940, © 2021 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Labour of Rest, Labour of Leisure

Commentary by Simon Ravenscroft

The three Synoptic Gospels each tell our story slightly differently, but all imply that Jesus, rather than the Pharisees, is the one who stands in continuity with God’s will for the Sabbath. This contrast is especially marked in Matthew, where the story comes directly after Jesus’s saying that, ‘my yoke is easy, and my burden is light’ (Matthew 11:30). Matthew’s framing implies that the Pharisees have made the law into a ‘burdensome yoke’ (Basser and Cohen 2015: 283). This is ironic given that the Sabbath is meant to bring rest from the burden of work. The Pharisees are presented in the Gospels as having turned the mandate to rest into an unnecessarily arduous religious labour.

Ben Shahn’s Handball was painted in 1939, using photographs taken in New York several years earlier as source material. The social context of the painting includes the phenomenon of ‘enforced leisure’, an initiative under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ to engage the unemployed in productive, community-building physical activity.

Shahn’s painting does not depict such organised collective exertion. Rather, it shows figures engaged informally and unofficially in a small-scale, improvised game; some are absorbed by it but others, in the foreground, adopt loitering postures. Considered in the social context of Depression-era America, this depiction ‘complicates the meaning of inactivity’, asking whether, in the absence of employment, leisurely play is only ‘productive’ when officially sanctioned (Fagg 2011: 1358).

One source from the time observes how, ‘enforced leisure drowned men with its once-coveted abundance … its taste became sour and brackish’ (Lynd and Lynd, 1937: 246). In contrast, in its depiction of informal, improvisatory play—generating absorption in some participants but loitering detachment, perhaps even boredom, in others—Handball suggests a vision of sport and leisure as organic and unburdened: ‘ritualised occurrences within ordinary, everyday life’ (Fagg 2011: 1366).

By comparison, Jesus interprets the Sabbath rules in a way that reemphasizes their role in meeting ordinary human needs and joys. The question of whether his followers’ way of resting is formally authorized by the religious officials of the day is incidental given that deeper purpose.

References

Basser, Herbert W. and Marsha B. Cohen. 2015. The Gospel of Matthew and Judaic Traditions: A Relevance-based Commentary (Leiden: Brill)

Fagg, John. 2011. ‘Sport and Spectatorship as Everyday Ritual in Ben Shahn's Painting and Photography’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28.8–9: 1353–69

Lynd, Robert S. and Helen Merrell Lynd. 1937. Middletown in Transition: A Study in Cultural Conflicts (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company)

Ben Shahn

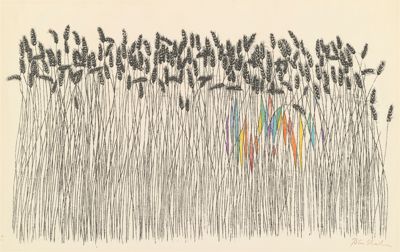

Wheat Field, 1958, Screenprint with hand-colouring, 686 x 1016 mm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Rosenwald Collection, 1959.10.51, © 2021 Estate of Ben Shahn / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Photo: National Gallery of Art, Washington

Seeing the Wood for the Trees

Commentary by Simon Ravenscroft

A striking feature of Ben Shahn’s print, Wheat Field, is the crowded use of line. Straighter and more orderly at the bottom, the stalks of wheat become criss-crossed and entangled at the top, difficult to follow and distinguish. Colours emerge where the lines overlap. Tracing the lines with your eye in the areas around these splashes of colour gives a sense of dynamism, as if the colours are light refracted through wheat that is moving in the breeze.

In the dispute between the Pharisees and Jesus’s disciples which is described in this incident in the gospel narratives, entanglement and dynamism are at issue.

Nowadays, seeing a group of friends ambling through a cornfield one weekend, picking off the odd ear of grain, one would easily define their activity as a form of leisure, unproductive but no doubt pleasant. Yet the gospel controversy is precisely the reverse: it is centred on whether such activity constituted ‘work’, in breach of first-century religious laws on Sabbath observance.

The disciples’ actions were not prohibited by biblical law. But the Pharisees, worried they might ‘accidentally or unknowingly transgress the will of God’, supplemented this written law with many additional regulations based in oral tradition (Hooker 2001: 103). Jesus’s followers are accused of breaching these extra rules.

Jesus sought a flexibility in the application of the Jewish Law (Torah) that the gospel writers contrast with the rigidity of the Pharisees. He appeals to deeper principles to guide its use: the Law exists to enrich human life rather than diminish it—‘the sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the sabbath’ (Mark 2:27 NRSV)—and human need takes priority over ritual observance—‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice’ (Matthew 12:7; Hosea 6:6).

It should not be assumed that Jesus’s attitude here is wholly revolutionary: there is Midrashic evidence that some other Jewish rabbis may have agreed with his position (Hooker 2001: 104). But with these remarks, Jesus implies that the Pharisees, so zealous to keep the law in minute details, had overlooked its underlying rationale.

The glimpses of colour seen through the wheat of Shahn’s Wheat Field might, therefore, be compared to how his interpretations seek to return to view, through a thicket of regulations, the essential purpose of the Torah: to bring life.

References

Hooker, Morna. 2001. The Gospel According to St Mark (London: Continuum)

Ben Shahn :

Supermarket No. 1, 1957 , Colour screenprint

Ben Shahn :

Handball, 1939 , Gouache on paper mounted on board

Ben Shahn :

Wheat Field, 1958 , Screenprint with hand-colouring

Living Work

Comparative commentary by Simon Ravenscroft

While our Gospel controversy is initially a technical one concerning whether Jesus’s followers had breached laws relating to Sabbath observance, it quickly develops into a dispute about the Law’s deeper purpose. Jesus is portrayed as a more faithful interpreter of the Law than the Pharisees, whose fixation on the minute details of religious observance is revealed as superficial, since it frustrates the Law’s essential goal: to be a blessing and a source of life.

The Gospels’ first readers in the early Christian communities would have found this story relevant for their own disputes about whether followers of Jesus (Jews but soon afterwards Gentiles too) were required to keep the Sabbath. Contemporary Gentile Christians are, as Hooker argues, likely to have understood it to mean that ‘they were not in any way bound’ by that command (Hooker 2001: 102). What is the significance of this for considering the status of work and rest for Christians?

By mandating a day of rest in imitation of God, the institution of the Sabbath relativizes the primacy of work in human life. Jesus’s interpretation of Sabbath rules—controversial to some of his hearers—does not undermine this general principle (other aspects of his teaching suggest a striking lack of interest in productive labour for its own sake—'Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them’; Matthew 6:26). Rather, it points forward to a further transformation of work, beyond a simple opposition of rest and toil.

As the late John Hughes argued, the ‘end’ of work (work’s goal) is not, for Christians, the end of work—all work ceasing, to be replaced by mere leisure—but its renewal, as something good. Alluding to the Sabbath healing story that comes directly after ours, Hughes writes: ‘the Sabbath is no longer a rest after creation, but is the day when the sick are healed, looking forward to the new creation, for as Christ says: “my Father is working still, and I am still working”’. Redeemed work is, like the Sabbath, to be a source of life rather than a drain on it: ‘…“work” that is also thoughtful, playful, restful, and delightful’ (Hughes 2007: 228).

Such a vision of work admittedly bears mixed resemblance to the alienated, stress-filled, joyless, unrewarding character of much modern wage labour. Ben Shahn was himself aware of this, being throughout his life a vigorous advocate for labour rights and improved working conditions. His three artworks featured in this exhibition attend in different ways to the transformed vision of labour described above, and do so partly as manifestations of his perspective on his own artistic vocation.

Handball—itself a depiction of improvisatory, informal play—is an example of what Shahn called his ‘Sunday paintings’: personal, small-scale works that he made for pleasure, as respite from formal commissions as a public muralist and documentary photographer during the New Deal (Fagg 2011: 1365). It embodies work, in other words, that for Shahn was Sabbath-like in its restorative, pleasant character.

Along the same lines, Shahn used a version of his Wheat Field print in an illustrated edition of Ecclesiastes, in which he identified the celebration of joyful labour in Ecclesiastes 3:22—‘I saw that there is nothing better than that a man should enjoy his work, for that is his lot’—as a central inspiration for his being an artist (Shahn 1967: preface). For Shahn, as for the writer of Ecclesiastes, the substance of good human living was work that could be rejoiced in.

What then of Supermarket as a symbol of American ‘daily life’? The artwork retains an ambivalence against the interpretive background we have been exploring here, in that its subject—grocery shopping—is a leisure activity that in a capitalist society is at the same time a sort of mundane necessity; a chore. But at the very least, as we ruminate on its boxy, angular play of line, shape, and colour, it can prompt us to consider in what contexts and forms of activity we ourselves find joy. Following the final trajectory of our Gospel passages, this may be the same as asking where we find our true work and true Sabbath; a question of what gives us life.

References

Fagg, John. 2011. ‘Sport and Spectatorship as Everyday Ritual in Ben Shahn's Painting and Photography’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28.8–9: 1353–69

Hooker, Morna. 2001. The Gospel According to St Mark (London: Continuum)

Hughes, John. 2007. The End of Work: Theological Critiques of Capitalism (Oxford: Blackwell)

Shahn, Ben. 1967. Ecclesiastes, or, the Preacher (Paris: Trianon Press)

Commentaries by Simon Ravenscroft