Psalm 85

Restoring Peace and Plenty

Unknown English Artist

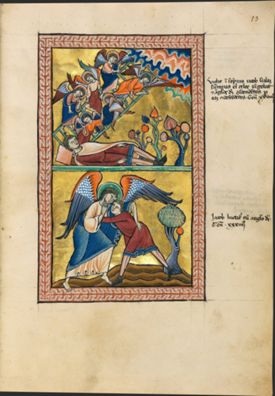

Miniature of Jacob’s Ladder and Jacob Wrestling the Angel (Genesis Cycle in Psalter), from the Munich Golden Psalter, c.1200, Illumination on vellum, 277 x 193 mm, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München; MS Clm.835, fol. 13r., Image: Courtesy Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Jacob’s Fortune Restored

Commentary by Jessica Savage

The sumptuous Munich Golden Psalter was made at the beginning of the thirteenth century for an important female patron from Oxfordshire. It is lavishly decorated, containing 91 full-page miniatures executed in five picture cycles with over three hundred biblical scenes in total. Most scenes in the manuscript are set against glittering, burnished gold backgrounds, making the Psalter a luxury production of the Middle Ages and bestowing it with ‘golden book’ (codex aureus) status.

On folio 13r, a prefatory miniature in the Genesis cycle depicts scenes from the life of Jacob in two registers. Above, Jacob dreams of a ladder between earth and heaven (Genesis 28:10–22), here stretched across a golden sky and climbed on by six angels. Their wings and turning bodies suggest their energetic movement to and fro between earth and heaven—represented by undulating bands of colourful clouds in the upper right corner of the miniature. Their continuous passage forms a link to Jacob on whom favour is being bestowed as he sleeps.

Psalm 85:1 opens with a powerful cry for God’s restoration of his people and revisits the story of Jacob as a reminder of the grace found through divine intercession: in the words of the Psalmist, ‘Thou wast favourable to thy land; thou didst restore the fortunes of Jacob’.

Central to this restoration is God’s mercy towards the sins of humanity as described in the following verses of Psalm 85:2–3. God’s mercy is likewise operative in the later, more perilous, episode in Jacob’s story depicted in the bottom register of this illumination. Here we see him wrestling with an angel (Genesis 32:22–32). The Psalter miniature captures a pinnacle moment in the match: the wrestlers are pressed head-to-head, their eyes are locked, and the angel’s left arm extends around the body of Jacob to wound him at the hip.

Though Jacob and the angel appear entangled in the height of battle, their posture as they tussle also closely resembles an embrace. The wound is not the last word. As if to indicate a truce, the angel makes a gesture of blessing over Jacob with his right hand, and effectively restores him as keeper of his inheritance.

References

Morgan, Nigel. 2011. Der goldene Münchner Psalter = The Munich golden psalter (Luzern: Quaternio Verlag)

Graham, Henry B. 1975. ‘The Munich Psalter’, in The Year 1200: A Symposium (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 301–08

Master François

The Parliament of Heaven and the Annunciation to the Virgin, from a Book of Hours, c.1470, Illumination on vellum, 140 x 98 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J.P. Morgan (1867–1943) with the Bennett Collection in 1902, MS M.73, fol. 7r., The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Where Virtues Meet and Kiss

Commentary by Jessica Savage

The illuminations in this late medieval Book of Hours, likely made in Paris in the 1470s to accompany prayer at intervals throughout the day, are attributed to the French artist known only as Master François (active c.1459–88). At the opening of Matins in the Hours of the Virgin, a full-page illumination depicts the meetings of the reconciled virtues in a scene allegorized from Psalm 85:10, here following the translation from the Latin Vulgate Psalm 84:11, ‘Mercy and Truth are met together, Justice and Peace have kissed’.

The iconographic features of this allegorical assembly (called the ‘Parliament of Heaven’, and also known in French as the Procès de Paradis or ‘Trial of Paradise’) were influenced by popular medieval Mystery plays that enacted a series of events imagined as taking place just before the Incarnation of Christ.

In the top register, in an arc of heaven filled with angels painted red en camaïeu (a monochrome painting technique), the throne of heaven resembles the iconography of the Trinity on a ‘Mercy Seat’ or in German a Gnadenstuhl. Christ holds the cross, the main instrument of his Passion, beside God the Father. Between them hovers the dove of the Holy Spirit. The open book they jointly hold represents their universal governance and power of judgement.

Directly below, the Archangel Gabriel, with green wings, kneels between two groups of female personifications joined together by their enfolding gestures. Mercy and Truth hold each other’s hands, and Justice and Peace press their faces together in warm familiarity.

In the lower register, and architecturally framed, is the familiar scene of Gabriel’s Annunciation to the Virgin where the archangel appears a second time to fulfil his new mission. Psalm 85, with its themes of revival and restoration, cannot be stressed enough as the affiliate setting of the Annunciation.

Above, a text window bears the Latin incipit (or opening phrase) of another Vulgate Psalm (50:17): ‘O Lord, thou wilt open my lips: and my mouth shall declare thy praise’. It suggestively echoes the Virgin’s words when she speaks to Gabriel, and foretells her subsequent psalm of praise known as the Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55).

References

Claggett Chew, Samuel. 1947. The Virtues Reconciled: An Iconographic Study (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

Camille Pissarro

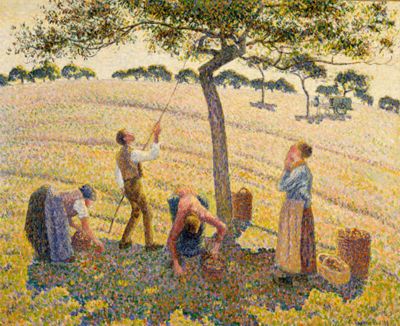

Apple Harvest, 1888, Oil on canvas, 60.96 x 73.98 cm, Dallas Museum of Art; 1955.17.M, Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art

Yield and Harvest

Commentary by Jessica Savage

In 1884, the Danish-French painter Camille Pissarro purchased a home in Éragny, a quaint village in northern France, which would serve as the setting for several of his paintings over the next decade. It was in Éragny that Pissarro would experiment with the pointillist technique, a novel application of paint that utilized a myriad of small dots of colour to form pictures.

Painted in 1888, Pissarro’s Apple Harvest depicts a sun-dappled field of apple trees and its workers. The scene is executed in hundreds of brushstrokes in a range of rainbow hues. Multiple bands of colour, suggesting furrows in the field, form a sloping horizon marked with several trees along the edge.

In the foreground, four people work under a tall apple tree with a crooked trunk and wide canopy. The tree’s shadow, which Pissarro executed in darker hues, provides a cool place for them to gather the harvest. Two women wearing aprons bend to collect fallen fruit, while another woman looks up at the jostling of tree branches by a man holding a long-handled tool. The harvest is collected in five baskets, most of them filled to the brim with ripe produce.

The closing verses of Psalm 85 are rich in the use of metaphor to describe God’s goodness as a plentiful harvest. Calling to mind Leviticus 26:4 and God’s promise of rain for crops, Psalm 85:12 says, ‘Yea, the Lord will give what is good, and our land will yield its increase’.

Pissarro’s Apple Harvest forms the very picture of fruitful increase yearned for in the words of the Psalmist, and in this case imparted after necessary labour and toil. In the distance, a horse-drawn wagon rolls along, suggesting the final verse of Psalm 85:13, ‘Righteousness will go before him, and make his footsteps a way’. Much like the cyclical nature of agricultural tasks, the Psalm’s end establishes a path that leads ever forward for the virtuous.

References

Karl, Klaus H. 2018. Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) (New York: Parkstone Press International)

Unknown English Artist :

Miniature of Jacob’s Ladder and Jacob Wrestling the Angel (Genesis Cycle in Psalter), from the Munich Golden Psalter, c.1200 , Illumination on vellum

Master François :

The Parliament of Heaven and the Annunciation to the Virgin, from a Book of Hours, c.1470 , Illumination on vellum

Camille Pissarro :

Apple Harvest, 1888 , Oil on canvas

A Good Ending

Comparative commentary by Jessica Savage

Augustine called Psalm 85 a psalm ‘for the end’, reflecting Christian belief in the fulfilment of Old Testament law through the birth of Christ. This fulfilment is most literally exemplified in the Book of Hours miniature by Master François of an imagined scene popular in medieval tradition—the Parliament of Heaven: a heavenly dispute over the sins of humanity. Here we see a depiction of the allegorical resolution of that dispute. The argument of the virtues—Justice and Truth demanding the atonement of sins while Mercy and Peace intercede for God’s pardon—ends with a divine ruling that yielded great goodness for the people. The Virgin would conceive Christ, the redeemer of sins, in a moment often depicted in the Annunciation as a small white dove—representing the Holy Spirit—gliding towards her on golden rays.

The descent of the Holy Spirit at the Incarnation finds a visual parallel in Jacob’s prophetic dream (Genesis 28:10–22) depicted in the Munich Golden Psalter. Here, the angels actively ascend and descend Jacob’s Ladder; their wings fluttering against an ethereal gold background in whose space they are suspended. They are charged with the mission to reach the exiled Jacob in his dream-state, and their ministry to him reaffirms a long-lasting channel of communication between God and his people.

At the heart of Psalm 85 is a plea for revival through dialogue with God, which finds a fitting culmination in Jacob’s story after his struggle with the angel. In Genesis 32, the climactic moment of Jacob’s fight ends in his blessing and renaming as ‘Israel’. He makes an emphatic proclamation: ‘For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved’ (32:30). He has had a revelation; in his angel opponent, he has met God. Through his relationship with God, even when that relationship takes the form of battle, Jacob finds himself sustained, changed, and ultimately renewed.

The Psalm’s theme of reconciliation is encountered in Master François’s depiction of the exchanges of the four virtues, pleading before the Archangel Gabriel and the Trinity in a judicial setting. It is also modelled by the greatest bearer of those virtues, the Virgin, as she accepts her role as the mother of Christ. Through her obedience, the Virgin will meet Christ for the first time at his birth in a relationship that speaks to the text of verse Psalm 85:11: ‘Faithfulness will spring up from the ground, and righteousness will look down from the sky’. The Archangel Gabriel, appearing twice in this Parliament of Heaven miniature, serves as a path through the composition both upwards to heaven and downwards to earth.

In all three works of art in this exhibition, the pairing of figures and their various means of touch bring aspects of Psalm 85 into sharper resolution. Jacob’s forceful push against the body of the angel provides a parallel to the female virtues, who meet and embrace each other as a form of reconciliation. In Camille Pissarro’s painting of the Apple Harvest, the actions of the four workers harmonize with each other as if to suggest communion through their joint occupation, and there is a shared physicality in the relationship they all have with their tools of work. The two women bending over in the scene busy themselves with the gleaning of the harvest into baskets. The male worker pushes his long-handled utensil upwards, inviting the gaze of another female worker who waits for the result of his rattling of the tree limbs. Ultimately, what we experience in Pissarro’s Apple Harvest is an image we can equate with the full restoration of God’s favour fervently longed after in Psalm 85. The harvest workers are dutiful and orderly, their crops abundant, and the idyllic French countryside exudes peace and plenty.

Pissarro’s use of the pointillist technique in his work invites viewers to step back from the picture and to be absorbed by the view. This is not unlike the larger message of Psalm 85, which revisits age-old and introspective questions about revival, restoration, and relationships among people, and between a people and their God. The main thrust of Psalm 85 touches on massive paradoxes experienced by every generation: loneliness (Jacob’s exile), struggle (Jacob’s wrestling the angel), dispute (the virtues’ disagreement), and certain toil—but also the promise of victory found through heartfelt connection.

References

Cleveland Coxe, A. (ed.). 1888. St Augustine: Exposition on the Book of Psalms, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series 1, vol. 8 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark), pp. 807–15

Commentaries by Jessica Savage