Luke 12:13–21

The Rich Fool

Adriaen Collaert, after Hans Bol

The Parable of the Rich Fool, from the Scenes from the Life of Christ (Emblemata Evangelica ad XII Signa Coelestia Sive), 1585, Engraving on laid paper, 152 x 207 mm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.365, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Interpreting the Present Time

Commentary by David B. Gowler

Emblemata Evangelica ad XII signa codestica (Evangelical Emblems Adapted to the Twelve Celestial Signs) was designed by Hans Bol, engraved by Adriaen Collaert, and published by Aegidius Sadeler. The twelve seasonal landscapes in the series correspond to the signs of the Zodiac. The Emblemata Evangelica seeks to combat idolatry by opening viewers’ ‘spiritual eyes’ to the mysteries of God’s kingdom, with the title plate noting that God created the stars (of the Zodiac), and that Jesus’s teachings call human beings to reject such ‘idolatrous worship’ and to worship ‘the sole Creator of all things’ (Melion & Clifton 2019: 151).

This landscape is depicted under the sign of Cancer (22 June–22 July). On the right, with three listeners beside him, Jesus points to the rich man who sits under a tree surveying his vast property—the early harvest being collected in the field; a nearby dovecote and beehives; cattle, chickens, and pigs grazing for food; and a barn being constructed.

Below the landscape a (Latin) quatrain—a stanza of four lines—summarizes the message:

The immense power of riches leads mortal men to vice, and they build new granaries for the produce of their fields, heedlessly placing all their safety in earthly might. But the man of low condition obtains the harvest and lays up the [heavenly] storehouse. (Trans. Melion & Clifton 2019: 151)

The print illustrates Jesus’s admonitions in Luke 12. Warnings against greed and the abundance of possessions (v.15), and about the fate of ‘those who store up treasures for themselves’ (v.21). Exhortations not to worry about what one will eat or wear but to strive for God’s kingdom instead (vv.22–23, 29–31), and to ‘sell your possessions and give alms’ (vv.33–34). And, in the context of the Zodiac, condemnations of those who ‘know how to interpret the appearance of earth and sky’ but do not know ‘how to interpret the present time’ (v.56).

References

Melion, Walter S. and James Clifton. 2019. Through a Glass Darkly: Allegory & Faith in Netherlandish Prints from Lucas van Leyden to Rembrandt (Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University)

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Money Changer (Der Geldwechsler), 1627, Oil on wood, 31,9 x 42,5 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Donated by Sir Charles J. Robinson in 1881, 828D, bpk Bildagentur / Art Resource, NY

Vanitas

Commentary by David B. Gowler

The dark room is illuminated by a single candle. An elderly man sits at a desk, a pince-nez perched on his nose, thoughtfully examining a coin. All peripheral elements are cloaked in shadows. The man’s hand blocks viewers from seeing the candle directly, but its glowing light brilliantly illuminates virtually every detail of his aged, wrinkled face. Other coins on the desk reflect the glow of the candle’s light, as do the metal clasps on the man’s shoulder and the ruff around his neck, which in turn projects even more light onto his face.

Who is this man, and what might this painting say to its viewers? The work resists immediate categorization and leaves many questions unanswered—even its subject is disputed. Some scholars argue that it depicts the parable of the Rich Fool (e.g. Tümpel 1971), but the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (correctly) titles it The Money Changer (Der Geldwechsler). This and similar works depicting an elderly person absorbed by material aspects of this world (e.g. Gerrard Honthorst, An Old Woman Inspecting a Coin, c.1623/4; see also Quinten Massys, The Moneylender and his Wife, 1514) personify avarice and vanitas, reminding viewers of their own mortality and the ultimate worthlessness of worldly possessions.

Rembrandt van Rijn’s manipulation of light and shadow, along with the man’s seemingly introspective detachment, create a sense of mystery. Yet the painting’s enigmatic qualities are engaging—just like Jesus’s ‘works of art’, the parables. The rays of light in Rembrandt’s work are reflected in various ways and sundry places, just as parables are reflected in different ways in different contexts and are understood in many ways by various interpreters. Rembrandt illuminates some objects clearly, while other aspects remain murky or obscure; placed in shadows; creating uncertainties and provoking debates.

For example, the man’s brilliantly lit face highlights his wrinkles, reddened nose, right ear, and eyelids, as well as the soft shadows produced by his glasses. By contrast, it is unclear, in the darkened room, whether the object behind the man on the upper left is a clock symbolizing the man’s approaching death or merely a stovepipe.

Similarly, Jesus’s parables illuminate some things clearly with other aspects remaining tantalizingly ambiguous. Is the rich fool, for example, an incompetent farmer who should have foreseen the extraordinary crop earlier? Or is he a shrewd agribusinessman who intends to hold back his harvest to receive a higher price for it later?

References

Gowler, David B. 2020 [2017]. The Parables after Jesus: Their Imaginative Receptions across Two Millennia (Waco: Baylor Academic Press)

Tümpel, Christian. 1971. ‘Ikonografische Beiträge zu Rembrandt. Zur Deutung und Interpretation einzelner Werke’, Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen 16: 20–38

James B. Janknegt

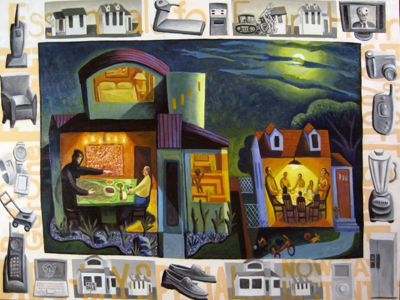

Rich Fool, 2007, Oil on canvas, 76.2 x 101.6 cm; Courtesy of James B. Janknegt

'The Things You Have Prepared, Whose Will They Be?'

Commentary by David B. Gowler

This parable’s subsidiary story—as the more muted colours suggest—unfolds on the painting’s border, whose background includes quotes from ads illustrating the consumerism that leads to the rich man’s fate (e.g. ‘Essentials for Every Hom[e]’).

The story begins at the top left with two small houses. Interspersed with the narrative episodes in the border are examples of the worldly goods that the rich man craves, and his acquisition of such goods leads to the following stage of the story in which the house on the left is bulldozed to build a mansion that will hold his increasing possessions. It is this mansion that is depicted in the third episode in the sequence (at bottom right). Continuing to move clockwise, the final scene shows a ‘For Sale’ sign in front of the mansion—the man has died—which reminds viewers of Luke 12:20: ‘And the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’

The border thus illustrates Jesus’s condemnation of avarice and its connection to wickedness (e.g. Luke 11:39). But the parable is ultimately about community: relationships with God and other human beings. The rich man of the parable isolated himself from others because of his wealth. He lacks community because greed inevitably leads to fractured relationships.

The interior image with rich, warm colours captures the central message of Jesus’s parable: the isolation that results from the destruction of relationships in contrast with the necessity of community.

In the mansion left of centre, the rich man dines alone in a large dining room, relaxing, eating, and drinking (12:19), while the angel of death announces his imminent demise (v.20). The contemporary modern artworks displayed in three rooms of the mansion are among the material goods the man has accumulated, and the sculpture in the room on the right could represent either the rich man’s heartlessness (personal correspondence with Janknegt 2024)—note the hole in the chest—or foreshadow the appearance of the angel of death.

In contrast, in the small house next door, a family of eight crowds around a dining room table. They are celebrating their life together—a family that symbolizes true human community of the sort that the rich fool should have attempted to build and maintain.

What remains worthy of preservation is the community found in this humble house, which is also a reminder that ‘life does not consist in an abundance of possessions’ (12:15).

Adriaen Collaert, after Hans Bol :

The Parable of the Rich Fool, from the Scenes from the Life of Christ (Emblemata Evangelica ad XII Signa Coelestia Sive), 1585 , Engraving on laid paper

Rembrandt van Rijn :

The Money Changer (Der Geldwechsler), 1627 , Oil on wood

James B. Janknegt :

Rich Fool, 2007 , Oil on canvas

‘Rouzing’ the Faculties to Act

Comparative commentary by David B. Gowler

William Blake once defended his art by saying, ‘The wisest of the Ancients considered what is not too Explicit as the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the faculties to act’ (Blake 2008: 702). Parables, too, can ‘rouze the faculties to act’—partly because they, like visual art, can have ambiguities that provoke divergent responses from interpreters.

Jesus’s parables focus extensively on issues of money and power. Jesus in Luke’s Gospel declares, for example, that wealthy elites should stop being ‘lovers of money’ (16:14) driven by greed. He chastises elites for their love of possessions and disregard of the poor (e.g. 14:7–24, where Jesus expects his wealthy host to ‘invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind’ to a feast). Jesus links the elites’ striving for money with their lack of concern for human beings, and this connection between riches and unrighteousness can only be broken by giving to the disadvantaged without expecting anything in return (14:12–14; see also 16:9, 19–31).

According to ancient farming manuals (written by and for elites), the rich man could be seen as a shrewd agribusinessman who hoards his crops until he can secure a higher price (e.g. Cato, On Agriculture 3.2), but God—in the only divine appearance in Jesus’s parables—calls the man a fool (see also Proverbs 11:26: ‘people curse those who hold back grain’). The rich fool exemplifies those who do not strive for the kingdom of God, whose treasure is material goods and ‘the abundance of possessions’ (12:15), and who do not care for those around them by selling their possessions and giving alms (12:33).

The man is foolish because he does not realize that ‘his’ abundant harvest comes from and ultimately belongs to God and that he has a responsibility to use it as God would want (see Isaiah 5:8). The man only ‘dialogued with himself’—in a soliloquy that includes referring to himself with ‘I’ or ‘my’ eleven times (12:17–19)—which demonstrates his isolation and lack of community. Jesus’s parable thus portrays the greed of a rich man who withholds perishable food from others who may be perishing. As Theophylact notes: ‘You have available to you as storehouses the stomachs of the poor which can hold much. . . . They are in fact heavenly and divine storehouses, for he who feeds the pauper, feeds God’ (Stade 1997: 147).

The ability to empathize—‘suffer with’ other human beings—becomes the decisive element in understanding what God requires and what this parable wants (12:33–34). Such privileged people attempt to use their wealth to protect themselves from the vicissitudes of life, but that effort erects barriers harming their relationships with others and with God.

A striking commonality thus appears in these images. In each one—in a darkened room, sitting outside under a tree on his vast property, or inside his well-appointed house—you see a person isolated, alone, out of touch with his fellow human beings.

In Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting, whether he is a money changer or the rich fool, the man’s avarice is clear (e.g. in the ways in which it participates in the genre paintings that depict greed). But, like Ebenezer Scrooge before the appearance of Marley’s ghost in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, judgement has not yet appeared. Nonetheless, viewers are warned about the ultimate futility of avarice by the portrayal of this elderly man who should by now know better.

In Adriaen Collaert’s print, in case the image is not enough to open viewers’ ‘spiritual eyes’, the quatrain warns how riches lead ‘mortal men’ to vice, though any hints of judgement are difficult to discern. In the background of the print, for example, life goes on. But does the cross-shaped object in the distance foreshadow Jesus’s death? Perhaps, yet any direct foreshadowing of the rich man’s fate in the landscape seems unlikely even for those with ears to hear and eyes to see.

James B. Janknegt’s painting, like many interpretations of the parable, makes the judgement clear by portraying the angel of death standing before the rich man and uttering the fateful declaration of doom. It is distinctive, though—if not unique—in its simultaneous portrayal of Jesus’s emphasis on the importance of building community.

All these images, whether implicitly or explicitly, illustrate that building God’s community (e.g. selling one’s possessions and giving alms) results in ‘an unfailing treasure in heaven’ (12:33).

References

Blake, William. 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. by David V. Erdman (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Gowler, David B. 2024. Howard Thurman and the Quest for Community: From Prodigals to Compassionate Samaritans (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press)

Stade, Fr Christopher. 1997. The Explanation by Blessed Theophylact of the Holy Gospel according to St Luke (House Springs, MO: Chrysostom)

Commentaries by David B. Gowler