Luke 16:19–31

A Reversal of Fortunes

Hendrick ter Brugghen

The Rich Man and the Poor Lazarus, 1625, Oil on canvas, 160 x 207.5 cm (with frame), Centraal Museum, Utrecht; 11241, © Collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht

A Textured Story

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

The scene is set like a stage. At the back, the Rich Man is entertaining a guest. He is dressed in a silk tunic, dyed with expensive purple in accordance with the story, and his table is covered in fine linen, bearing a still life consisting of a large fish on a metal dish, a plate with juicy green olives, a bread roll, a small carafe, and two more pewter plates. The Rich Man holds a wine-filled flute glass while instructing an approaching maid.

In the spotlight in the foreground, we see the bony, nearly naked figure of Lazarus resting on a stone in a languid pose, barely holding himself upright with a rough stick. Again according to the story, two dogs have come to lick the dark sores that mar Lazarus’s bare legs. They are hunting dogs, as would befit a wealthy man, and the painter appears to have taken delight in rendering the cute animals’ well-brushed, spotted fur.

A richly dressed man-servant in a feathered cap is trying to shoo away the ungainly beggar from his master’s doorstep; the servant is not mentioned in the parable, but is often included in visual representations to accentuate the Rich Man’s derogatory attitude toward the poor.

Although the subject is biblical, this large painting was not made for a church, but for a private household. And while the represented scene purportedly offers religious instruction, exhorting the viewer to Christian charity, it is also a rich catalogue of the artist’s skills in depicting a wide range of textures, from the crisp table linen and the shiny pewter of the plates to the soft flesh of the fish and the moist olives; from Lazarus’s rough, scabbed skin to the strokeable fur of the dogs and the glitteringly gold scarf wrapped around the servant’s waist.

Ironically, this demonstration of artistry must have been in itself a pricey work that a seventeenth-century Rich Man would have proudly displayed on his wall as a manifestation of his wealth.

References

Domela Nieuwenhuis, E. 2007. ‘De rijke man en de arme Lazarus door Hendrick ter Brugghen 1625’, in Stichting Victor: restauratie en natuurwetenschappelijk onderzoek in the Centraal Museum, Liesbeth Helmus et al. (Utrecht: Centraal Museum) 78–95

Unknown Cretan artist

The Rich Man in Hell, Late 14th century, Wall painting, Church of Christ the Lord, Kritsa [Lassithi, Crete]; © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports (N.3028/2002), Hellenic Μinistry of Culture and Sports–Archaeological Resources Funds; Photo: © Angeliki Lymberopoulou

Thirst for Redemption

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

The Rich Man is hunched naked amidst the flames of hell, looking up at paradise where the once poor Lazarus is sheltered in Abraham’s bosom. The image is graphic like a comic book illustration. It even has a speech bubble, with (in medieval Greek), the Rich Man’s invocation: ‘Father Abraham, have mercy upon me, and send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in anguish in this flame’ (Luke 16:24). As if to clarify—perhaps for those medieval viewers unable to read—the Rich Man sticks out his tongue and touches it with his index finger.

It is not difficult to imagine a medieval audience quietly chuckling with Schadenfreude at the fate that has befallen this arrogant representative of the economic elite.

The painting is part of the rendering of paradise and hell in a cycle of the Last Judgement in a church in the small town of Kritsa on eastern Crete. Countless such wall paintings were made across the length and breadth of Crete in the fourteenth century, material testimony to the wealth generated on the island during the period when it was a dominion of Venice. Crete was an important way-station on Venice’s trade routes to the Middle East and the Venetians stimulated agriculture and the exploitation of natural resources such as wood and salt, shipping Cretan commodities to the far corners of Europe. The income of this trade appears to have trickled down to towns and villages, where it was used to build and decorate churches.

Yet, despite this fair distribution of wealth, the message of the consequences of economic inequality embedded in the story of the Rich Man and the Poor Lazarus does not seem to have lost any of its potency in this representation.

References

Lymberopoulou, A. (ed.). 2020 [forthcoming]. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Lymberopoulou, A. and D. Duits. 2020 [forthcoming]. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Artwork Institution Details

Τα δικαιώματα επί του απεικονιζόμενου μνημείου ανήκει στο Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού (ν.3028/2002) [© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports (N.3028/2002)] Το μνημείο υπάγεται στην αρμοδιότητα της Εφορείας Αρχαιοτήτων Λασιθίου. Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού-Ταμείο Αρχαιολογικών Πόρων και Απαλλοτριώσεων. [Hellenic Μinistry of Culture and Sports–Archaeological Resources Funds]

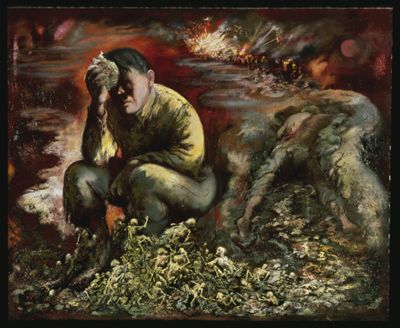

Georg Grosz

Cain, or Hitler in Hell, 1944, Oil on canvas, 99 x 124.5 cm, David Nolan, New York; GG2678, © Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Photo: bpk Bildagentur / Art Resource, NY

Getting One’s Comeuppance

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

The world’s most infamous vegetarian is reduced from his own self-fashioned image of triumphant statesman and war leader to a brooding figure mopping his sweating brow with a crumpled kerchief as the realisation dawns on him that there are, after all, no deeds without consequences—not even for der Führer.

He sits hunched in an amorphous landscape, next to a corpse lying face-down in the mud—an echo of an earlier pictorial composition in which the artist, the exiled German satirist Georg Grosz, had represented the Nazi dictator as Cain having killed his brother. In the background, burning buildings produce a sinister glow. The hell to which he is condemned is of his own making, the product of the destruction that he has wrought. A host of skeletons rises up from the earth around his feet and has started clambering up his legs, threatening to overwhelm him: his innumerable nameless victims are coming for revenge.

Modern Western Christianity tends to put an emphasis on ‘turning the other cheek’ and ‘he that is without sin’ casting the first stone (John 8:7). The message of Christ, in this modern interpretation, is one of forgiveness. Yet, the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus is in essence about an uncharitable person getting what he deserves. The one story in the New Testament that deals with the specifics of the afterlife tells us ‘behave, or else...’

This must have been an important part of the story’s appeal over the ages, as it is an important aspect of the way that Christians have imagined hell—a place where the unjust, the law-breakers, and the morally corrupt pay the price of their behaviour.

Georg Grosz has effectively co-opted the Western tradition of hell imagery that was inspired by the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus to condemn one prime candidate for ‘most evil man of history’ to a fate in which we cannot help but find at least a little satisfaction.

References

Schmölders, Claudia. 2009. Hitler’s Face: The Biography of an Image, trans. by Adrian Daub (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), esp. p.191

Hendrick ter Brugghen :

The Rich Man and the Poor Lazarus, 1625 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Cretan artist :

The Rich Man in Hell, Late 14th century , Wall painting

Georg Grosz :

Cain, or Hitler in Hell, 1944 , Oil on canvas

Before and After

Comparative commentary by Rembrandt Duits

It is the classic before-and-after story. During their short span upon this mortal coil, the Rich Man has it all (expensive purple clothes, fine linen, sumptuous food), while the poor Lazarus begs for scraps from his table. The idea that the Rich Man does not want to grant him even these scraps is not spelled out in the biblical passage, but appears to be implied, and is certainly made explicit by artists concentrating on the first phase of the story. Hendrick ter Brugghen, in his painting in the Centraal Museum in Utrecht, shows a servant gesturing to send the beggar packing, away from his master’s house.

Then, after the watershed of death, Lazarus, having born his sufferings on earth, is rewarded with eternal bliss in the bosom of Abraham in paradise, while the Rich Man is tormented by unquenchable thirst amidst the fires of hell. A chasm gapes between them at least as wide as the social and economic chasm that separated them during their lifetimes.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus is the only biblical passage that describes what happens to the soul after death with any degree of specificity. For sinners, there are other more generic references in the Bible, to the everlasting fire (Matthew 25:41; Mark 9:44–48), the outer darkness (Matthew 8:12), and the sleepless worm (Isaiah 66:24), suggesting degrees of unpleasantness in the afterlife. Yet, there are no other references to individual souls in either heaven or hell in Scripture.

In Byzantine art, the parable was therefore seized upon by artists as an authoritative image of the posthumous fate of the soul. For centuries, the Rich Man was the only individual to be shown inhabiting hell, sitting surrounded by flames and pointing in desperation at his thirsty mouth, as in the painting by an anonymous master from Crete shown here. He then—in Byzantine painting from the twelfth century onwards—became the model for other pictures of individual sinners subjected to various torments appropriate to the transgressions they had committed (Byzantine artists revelled in the concept of poetic justice even before Dante made it the guiding principle of his Inferno in the early fourteenth century).

Theologians have debated whether the descriptions of the parable should be taken literally or metaphorically, and whether the souls of the Rich Man and Lazarus are meant to be undergoing their respective rewards directly after death or in the period following the Last Judgement (when the final segregation of souls is meant to take place). For ordinary people, however, these finer points of theology were always irrelevant, and the parable offered a simple, direct message: indulge in riches and you will end in hell; endure poverty and you will find solace in heaven. This is likely to have been what the people from a small town on Crete in the fourteenth century thought when looking at the wryly comical representation of the Rich Man with his parched tongue on the wall of their church: ‘Serves you right, mate’.

Two works—the wall painting by the anonymous Cretan master and Hendrick ter Brugghen’s canvas—illustrate different phases of the parable, and seize upon different aspects of the story. The one is a stark, almost farcical rendition of the fate of the ‘bad guy’ of the story; the other an evocative rendition of the contrast between rich and poor in the first, earthly stage of the narrative. Their message may have overlapped, however, as the viewers of Ter Brugghen’s painting, too, would have been pondering the imminent reversal of fortunes of the two protagonists. They were probably rich themselves and it is to be hoped the painting would have inspired them to be charitable.

The last work included here is not an illustration of the parable, but an off-shoot of the rich iconographical tradition of hell that it engendered. The German satirist Georg Grosz (1893–1959) practised a brand of social commentary and used an expressionist idiom in drawings and paintings in the inter-war years in Germany, which ultimately led to him becoming a fugitive from the Nazi regime, living in exile in America. There, he applied, with evident relish, and echoing some of the black humour of the medieval tradition, the paraphernalia of the inferno and the idea of reaping the rewards for reprehensible behaviour to the archetypal bad guy of the twentieth century.

References

Detlev Sievers, Kat. 2005. Die Parabel vom reichen Mann und armen Lazarus im Spiegel bildlicher Überlieferung (Kiel: Verlag Ludwig)

Lehtipuu, Outi. 2007. The Afterlife Imagery in Luke’s Story of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Leiden and Boston: Brill)

Wolf, Ursula. 1989. Die Parabel vom reichen Prasser und armen Lazarus in der mittelalterlichen Buchmalerei (Munich: Scaneg)

Commentaries by Rembrandt Duits