Matthew 18:6–9; Mark 9:42–48; Luke 17:1–2

The Road to Oblivion

Unknown artist

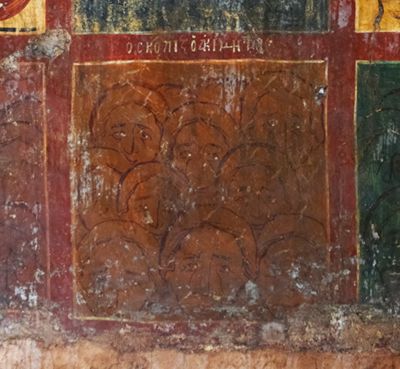

The Sleepless Worm, 1452–61, Wall painting, Church of Saints Constantine and Helena, West wall, Voukolies (Kissamos), Chania, Crete; Photo: © Angeliki Lymberopoulou

The Sleepless Worm

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

This passage in the Gospel of Mark instructs the Christian faithful to cut off any member of their body that may lead them to temptation because it is preferable to be physically mutilated than risk spending an eternity in hell where one of the punishments is to be eaten by the worm that never dies.

Byzantine Christian iconography visualized this as the ‘Sleepless Worm’, commonly identified by Greek inscriptions as such (ο σκώληξ ο ακοίμητος, o skōlēx o akoimētos), one of the six compartments of Communal Punishments located in the lowest part of hell. There, all individual characteristics are obliterated and the sinners are crowded together in a tense, claustrophobic space.

The representation of hell was often illustrated in the monumental art of Venetian Crete (1211–1669), and in the island’s rich iconographic programmes this compartment is the second most popular. The Church of Saints Constantine and Helena includes an example which artists (using their artistic licence!) frequently employed when depicting this punishment. The compartment is shown as a square defined by a thick red line and identified as ‘the Sleepless Worm’ by an inscription written in white Greek capital letters. Against its ochre background, rows of heads are tightly packed, attacked by little, white, wiggly worms (in their multiplicity representing the single worm of the passage). While the people’s bodies are not depicted, their hair and facial characteristics are clearly visible; they seem to have both of their eyes intact, perhaps as a suggestion that these people did not follow the Gospel’s advice (9:47) and are now paying the hefty price.

Considering that at the time the majority of the population was illiterate, it would have been the white, wiggly lines, identifying the worm—and hence the passage—that would have been far more useful to the congregation for comprehending this scene and the powerful biblical message of judgement it conveys.

References

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki (ed.). 2020. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 1, Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

______. and Rembrandt Duits. 2020. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 2, A Catalogue of the Cretan Material (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Maltezou, Chryssa. 1991. ‘The Historical and Social Context’, in Literature and Society in Renaissance Crete, ed. D. Holton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 17–47

Unknown artist

Icon with St Sisoes and the Skeleton of Alexander the Great, 16th century, Tempera on panel lined with canvas, 26.7 x 19.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; akg-images / Album

I Cannot Believe My Eyes

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

Saint Sisoes (367–429 CE) was an Orthodox hermit who lived in Egypt, where the tomb of Alexander the Great (356–23 BCE), one of the most admired personalities of all times, was also located.

After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, the ephemeral nature of life became a focus of Orthodox thought. The subject of this icon captures this notion: a large, kneeling figure dominates the mountainous landscape set against a gold background. A halo outlined in red identifies the figure as a saint, while an inscription in capital Greek letters—written also in red—reads ‘Saint Sisoes’. His arms are raised, his palms facing outwards, underlining his astonishment at the skeleton in the grave before him, identified in Greek script as ‘Alexander the Great’.

The edge of the grave is also inscribed in Greek: ‘I see you and I am afraid—who can escape you?’. As a saint, Sisoes was not himself afraid of death, yet the icon expresses his sadness at its inevitability. Death is the destiny of all humans, regardless of their achievements in this life.

This powerful scene might also be considered in relation to the worm that never dies, as described in Mark—always working its way until nothing remains. In this case, the worm may be understood as synonymous with death, which (as this icon’s inscription reminds us) is inescapable. Thus iconography comes together with the text of the Gospel to highlight to the faithful the futility of this life.

John Chrysostom wrote of this passage:

Their fire shall not be quenched, and their worm shall not die’. Yes, I know a chill comes over you on hearing these things. But what am I to do?

But there would be no gain, Chrysostom insists, in avoiding the challenge of Jesus’s words—for:

[t]his is no trivial subject of inquiry that we propose, but rather it concerns things most urgent. (Homilies on Corinthians, IX.1)

References

Bormpoudakēs, Manolēs (ed.). 1993. Eikones tēs Krētikēs technēs: apo ton Chandaka hos tēn Moscha kai tēn Hagia Petroupolē (Hērakleion: Vikelaia Dēmotikē Vivliothēkē), pp. 345–47

Hetherington, Paul (trans.). 1981. The ‘Painter’s Manual’ of Dionysius of Fourna, rev. edn (London: Sagitarius Press), p. 60

John Chrysostom. Homily IX. 1889. Trans. revd by T. W. Chambers. Homilies on the Epistles of Paul to the Corinthians, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series 1, vol. 12, ed. by Philip Schaff (New York: Christian Literature Publishing)

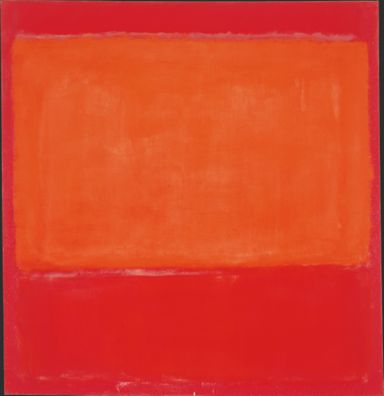

Mark Rothko

Orange and Red on Red, 1957, Oil on canvas, 175 x 168.6 cm, The Phillips Collection; Acquired 1960, © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Any reproduction of this digitized image shall not be made without the written consent of The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Lost in Red

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

Mark Rothko (1903–70) is known for his prolific production of large canvases combining a palette of meticulously-chosen colours with a different dominating colour (or colours) in each. It is these creations which earned him a pronounced reputation on art’s world stage. Orange and Red on Red is one of these creations.

While Rothko’s work is not a direct response to this passage from Mark, it is nevertheless possible to make connections between this painting and the Gospel narrative, especially if one is of the Christian faith. In the first place, Rothko himself said, ‘There is no such thing as good painting about nothing’ (Rothko and Gottlieb 1943), and declared that he was ‘interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on’ (Bishop 2017: 12). Few feelings could be more basic or more powerful than those incited by the idea of the afterlife. Hence, the dominant red colour would make it easy to associate it with the constantly repeated reference of Mark 9 to the fire which ‘is not quenched’. Since the worm that never dies is equally repeated along with the fire, that too may be awakened in a viewer’s imagination. In addition, the white brushstrokes that appear on the canvas do bring to mind the shape and colour associated with worms.

Rothko’s works have been hailed as ‘an experiential connection between the viewer and the art’ (Bishop 2017: 11), as they invite people to engage with the painted surface, to ‘dive’ into it and make it their own. So there seems every reason to welcome the religious associations that can awaken when the texts and images of Christian faith come into dialogue with this work—when, following its creator’s advice, the faithful attempt to ‘experience’ it from their particular perspective.

The worm that never dies may consume all, until everything blends into a captivating, colourful emptiness.

References

Bishop, Janet. 2017. Rothko: The Color Field Paintings (San Francisco: Chronicle Books)

Rothko, Mark and Adolph Gottlieb. 1943. ‘Letter to Edward Alden Jewell, Art Editor, The New York Times, 7 June 1943’, printed in E. A. Jewell, ‘The Realm of Art: A Platform and Other Matters; “Globalism” Pops into View, 13 June 1943’, The New York Times, p. 9

Unknown artist :

The Sleepless Worm, 1452–61 , Wall painting

Unknown artist :

Icon with St Sisoes and the Skeleton of Alexander the Great, 16th century , Tempera on panel lined with canvas

Mark Rothko :

Orange and Red on Red, 1957 , Oil on canvas

Nothing Good Here: Only the Bad and the Ugly

Comparative commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

The passage from Mark’s Gospel offers advice to the Christian faithful on how to obtain an eternal afterlife, and (more specifically) how to avoid the punishments of hell.

Mark 9:48 (and also vv.44, 46 in the Vulgate translation and the KJV) mentions the ‘worm [that] dieth not’. The passage makes vivid Christ’s teaching that any body parts (hands, feet, eyes, etc.) that commit sinful acts should be eliminated, because it would be preferable to be maimed rather than go to hell for eternity.

Commonly known as the ‘Sleepless Worm’ on the basis of inscriptions in Greek script that accompany its Byzantine iconography, this ‘worm that dieth not’ may be perceived as a visual representation of the inevitable natural decay to which all living organisms are subjected sooner or later. One of the main promises of Christianity however—a bodily afterlife for those proven worthy—nullifies this natural decay. Those who succeed in entering eternal life will not have to be subjected to the endless work of the dreadful worm.

The biblical passage, with its echoes of Isaiah 66:24, does not offer any descriptive details of the ‘worm’—perhaps adding to the gruesomeness of the image by leaving the listeners to their own devices to imagine it. It was left to artists to create visual images that would reflect the passage. The example of the Sleepless Worm from the Church of Saints Constantine and Helena in Voukolies presents an example of the monumental Byzantine art of Venetian Crete, featuring rows of heads with white undulating lines crawling over them. The intact facial characteristics of the tightly packed heads suggest that the work of the worm has just started. This wall painting therefore serves well as a prelude to the other two works in this exhibition.

It could then be argued that the Byzantine icon in which Saint Sisoes discovers the skeleton of Alexander the Great presents a step further down the line of the worm’s fearful work. Sisoes was a hermit in Egypt, where the tomb of Alexander the Great was also located, a geographic proximity that confirms the actuality of the encounter. Alexander the Great, the Greek king of Macedon, was one of the most-admired generals of all time. In his short lifespan he conquered a remarkable amount of the then-known world, and never lost a battle. Regardless of his great achievements when alive, and his posthumous fame, Saint Sisoes’s encounter with the great ruler’s remains underlines that no achievement in this ephemeral life can prevent the worm that never dies from attacking the bodily vessel of the immortal soul. This iconographic subject, which became popular after the loss of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, is usually accompanied by an inscription in Greek, just like the one seen at the bottom part of the sarcophagus facing the viewer, that conveys Sisoes’s stark realization of the inevitability of death. This encounter invites a reflexion on Mark’s passage by confirming that the only thing one can do in this ephemeral life is to prepare for the next.

If we were to consider Mark Rothko’s painted canvas as the third part of this sequence, it could serve to suggest the empty vastness following the all-consuming labour of the worm. The dominant red colour in this work could well allude to the fire that ‘shall not be quenched’, which is repeated next to the ‘worm that dieth not’ in Mark’s passage. Hence, looking at these artefacts in succession, Rothko’s can serve as a third stage in the gradual visualization of decay: the Byzantine wall painting presents the worm at the launch of its attack; the skeleton in the panel demonstrates the progress of the worm’s tireless effort; and Rothko’s canvas shows the aftermath of the worm’s all-consuming toil, a perfect representation of the inevitability of death that annihilates everything.

As Mark’s passage admonishes, Christianity provided an alternative to inevitable obliteration for those following its teaching faithfully. Viewed in combination with the passage, this artistic ‘trilogy’ could be perceived as a wagging finger counselling us against a false focus on the ephemeral life which cannot possibly defeat death, and which is bound ultimately to succumb to the ‘worm [that] dieth not’.

References

Bishop, Janet. 2017. Rothko: The Color Field Paintings (San Francisco: Chronicle Books)

Bormpoudakēs, Manolēs (ed.). 1993. Eikones tēs Krētikēs technēs: apo ton Chandaka hos tēn Moscha kai tēn Hagia Petroupolē (Hērakleion: Vikelaia Dēmotikē Vivliothēkē), pp. 345–47

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki (ed.). 2020. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 1, Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

———. and Rembrandt Duits. 2020. Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 2, A Catalogue of the Cretan Material (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Commentaries by Angeliki Lymberopoulou