Matthew 18:10–14; Luke 15:1–7

The Parable of the Lost Sheep

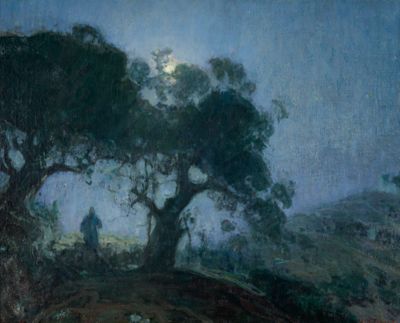

Henry Ossawa Tanner

The Good Shepherd, 1902–03, Oil on canvas, Stretcher: 68.5 x 81.2 cm, Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey; In memory of the deceased members of the Class of 1954, 1988.0063, Photo: Peter Jacobs. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University

Who is the shepherd?

Commentary by Joy Clarkson

After the critical success of his painting The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896), African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) travelled to the Holy Land driven by a desire to paint biblical scenes that were as faithful to their cultural and historical context as possible (Woods 2017: 124). He was struck by the overlap of past and present; by how little the landscape and lifestyle of Jerusalem seemed to have changed since the times of Jesus.

He evokes this sense of continuity in his painting The Good Shepherd (1903). Two ancient trees dominate the horizon, which have presumably watched over the treacherous mountain path for many centuries—perhaps since the time of Christ, or even of King David.

The scene is set at night with the silhouettes of the shepherd and his sheep outlined against deep blues and misty greens. The landscape is illuminated only by a moon whose rays are obscured by spindly branches. The nocturnal setting brings to mind the Psalmist’s words:

Even though I walk through the darkest valley,

I fear no evil;

for you are with me;

your rod and your staff—

they comfort me. (Psalm 23:4, NRSV)

By uniting the imagery of the Hebrew Bible and Jesus’s parable of the Good Shepherd with the contemporary landscape of Palestine, Tanner evokes the constancy of God’s divine and loving care: the God who cared for his sheep in the times of David and of Jesus will care for humankind even still. But now, as then, this guidance often takes place in the dark; it requires trust, patience, faith. And the journey through the Valley of the Shadow of Death is one which David, Christ, and every human being must face.

References

Woods Jr., Naurice Frank. 2017. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Art, Faith, Race, and Legacy (Milton Park: Taylor & Francis)

Richard Ansdell

The Rescue, 1866, Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 148.6 cm, The Lytham St Annes Art Collection, Lancashire; Alderman and Mrs J H Dawson on the occasion of thanksgiving for victory, May 1945, 72, Courtesy of the Lytham St Annes Art Collection of Fylde Council

How much Trouble is a Sheep Worth?

Commentary by Joy Clarkson

Inspired by a four-month stint of shadowing shepherds in the Scottish Highlands, Richard Ansdell’s (1815–85) gripping painting The Rescue manages to portray just how much trouble it would be to rescue a lost sheep.

The viewer is confronted with steep cliffs, jagged rocks, and the foreboding shadow of a carrion bird which the shepherd’s dog watches with alert concern. It is not only the one lost sheep that is in peril; in the background the rest of the herd waits by the loch, apparently contented but clearly vulnerable, overshadowed by an ominous raincloud. Whether or not the artist intended to reference the scriptural parable, transposing the drama of retrieving a sheep from the hills of ancient Israel to the brooding landscape of Scotland refreshes the sense of struggle and risk involved in the task of rescue that Jesus describes.

This parable centres around a question: ‘What do you think? If a shepherd has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray?’ (Matthew 18:12). The way the question is asked seems to imply an affirmative answer, but this painting reveals that a ‘yes’ is by no means self-evident. From the danger to the rest of the flock, to the immense physical and practical burden, to the potential economic loss, such a calculation makes no sense, and yet to Jesus such a venture is clearly worth it.

Jesus’s evident loyalty to pursuing the one sheep illuminates the care of the Divine Shepherd, whose love is not utilitarian, efficient, or disinterested. Indeed, the trouble seems to increase his joy: ‘he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray’ (Matthew 18:13). The Shepherd delights most in his troublesome sheep.

John Piper

Photograph of a sheep on Romney Marsh, Kent, c.1930s–80s, Black and white negative, 58 x 62 mm, Tate; Presented by John Piper 1987, TGA 8728/1/20/150, ©️ 2022 The Piper Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London; Photo: ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Who are the Sheep?

Commentary by Joy Clarkson

This photograph is part of a series taken of Romney Marsh in Kent by the painter, printmaker, and designer John Piper (1903–92). It depicts a Romney sheep, a breed admired throughout the centuries for its fine wool and ability to thrive in unfriendly climates. The Romney Sheep Breeder’s Association writes that the breed has a ‘reputation for soundness of feet and good resistance’ (‘About’, n.d.)—a description which captures well the sheep in Piper’s photograph, who seems to challenge the viewer, its gaze direct, its ears extended in alert attention.

Over the course of Christian history, there has been much conjecture about the attitude of the sheep in the parable of the Lost Sheep. Perhaps thinking of the sheep in his own native Essex, the influential preacher Charles Spurgeon (1834–92) describes sheep as utterly incapable of caring for themselves: ‘Of all wretched creatures a lost sheep is one of the worst’ (Spurgeon, ‘Lost Sheep’, 1884). Others emphasize the wilfulness of sheep as an allegory of humankind’s proclivity to sin and wander away. ‘Sheep are stubborn’, writes Augustine. ‘What do you want us for’, he imagines the sheep asking Jesus; ‘Why are you seeking us out?’ (Augustine, Sermon 46).

One could imagine either attitude (senselessness or stubbornness) in the piercing stare of the Romney sheep in Piper’s image. Perhaps it has wandered away on purpose and does not wish to be found; its breed is known, after all, for resilience in difficult terrain. And yet there is also a helplessness in its rebellion, mired amongst spiky plants with no clear exit route. The Jesus of the Gospel of Matthew seems not primarily to be interested in the reason the sheep is lost (by contrast with Luke, whose sheep illustrates the effects of sin; v.7). Matthew’s focus is on the persistence of the shepherd towards his ‘little ones’ (vv.10, 14).

Like the sheep in Piper’s photograph, the lost sheep of Jesus’s parable may be rebellious or pitiable; it remains unclear which. But this we know: it is seen and sought out.

References

‘About’, Romney Sheep Breeder’s Association, available at https://www.romneysheepuk.com/about [accessed 11 August 2022]

Rotelle, John E. (ed.), Edmund Hill (trans.). 1990. Sermons, vol. 2, The Works of St Augustine (Brooklyn: New City Press), p. 272

Spurgeon, Charles Haddon. 1884. ‘The Parable of the Lost Sheep’ (Sermon, September 28th, 1884), Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit, 30 (London: Banner of Truth Trust), pp. 517–28

Henry Ossawa Tanner :

The Good Shepherd, 1902–03 , Oil on canvas

Richard Ansdell :

The Rescue, 1866 , Oil on canvas

John Piper :

Photograph of a sheep on Romney Marsh, Kent, c.1930s–80s , Black and white negative

Do Not Despise One of These Little Ones…

Comparative commentary by Joy Clarkson

One of the most ancient and well-beloved metaphors for God is that of a shepherd. ‘The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want’, writes the Psalmist (Psalm 23:1, NRSV), a designation Jesus readily adopts for himself: ‘I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep’ (John 10:11, NRSV). From the frescoes in the shadowed catacombs of the early church, to medieval stained glass, all the way to the present day, the image of God as shepherd has remained a constant source of inspiration for Christian theology, art, and devotional practice. Each of the artworks in this exhibition invite viewers to consider different dimensions of the drama of the lost sheep.

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting evokes the primordial fear of darkness; the universal need for guidance and protection. By mingling the imagery of the Old Testament with the language of the New Testament and landscape of his own day, Tanner emphasizes the essential precarity of human existence. While it is easy to imagine some distinction between the Pharisees Jesus addressees and the lost sheep in his parable, the earliest exegetical texts almost universally see the sheep not merely as a singular sinner, but as representative of the whole of humanity, alike to the prophet Isaiah’s words:

All we like sheep have gone astray

we have all turned to our own way,

and the Lord has laid on him

the iniquity of us all. (Isaiah 53:6, NRSV)

In Jesus’s words, then, there is an invitation for the Pharisees to understand themselves as the sheep in need of saving. They too need guidance along the treacherous path of life; they too will walk through the valley of the shadow of death.

While Tanner’s painting draws our eyes to the figure of the shepherd, John Piper’s photograph directs our attention to the sheep, who gazes at us with ambivalent intensity. In Luke, the parable of the Lost Sheep comes as a rebuke, one of three parables that Jesus tells in response to the ‘grumbling’ of the Pharisees about the company that he chose to keep—namely, that of tax collectors and sinners (15:1). The parable comes as an affirmation that God loves, values, seeks, and cares for those whom the world considers not to be worth very much effort: children, outsiders, recalcitrant sinners, senseless sheep. While it is the nature of human love to favour the good or at least the thankful, God’s love does not make calculations based on the attitude of the sheep, be it—as with the ambiguous Romney sheep—plaintive lostness, or be it stubborn opposition.

Richard Ansdell’s painting puts on display the enormity of effort and risk that the rescue of one sheep might require; the shepherd risks his own safety in the endeavour, and that of the entire flock. Aside from the more practical concerns of safety and economy, the early Christian author Tertullian (155–220 CE) observes that even tedium might prevent such a search: ‘impatience would readily take no account of a single sheep, but patience undertakes the wearisome search’ (‘On Patience’, 12). Yet, Jesus makes no such calculations. To Jesus, the value of the sheep is inherent, inviolable, and demands action.

Jesus does not, however, cast the rescue of the sheep in the wooden vocabulary of disinterested duty. On the contrary, the shepherd’s pursuit of the sheep seems to highlight its value, and to increase the shepherd’s joy. Jesus implies that not merely are all sheep valuable, and that the shepherd looks after them all, but that it is the delight of the Divine Shepherd to do so.

In Matthew’s version, the parable of the Lost Sheep follows a scene in which Jesus welcomes children into the circle of his ministry, admonishes his followers to become childlike, and issues strong threats against those who would harm or belittle children. The admonition to ‘take care that you do not despise one of these little ones’ (Matthew 18:10) is fulfilled by the shepherd, whose delight it is to care for his flock, no matter the danger, the trouble, or the attitude of the sheep.

References

Just Jr., Arthur A., and Thomas C. Oden (eds). 2003. Luke, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, New Testament 3 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press), pp. 243–46

Marley, Anna O. (ed.). 2012. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (Oakland: University of California Press)

Mathews, Marci. 1994. Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Tomkinson, Theodosia (trans.). 1998. Ambrose of Milan: Exposition of the Holy Gospel According to St Luke (Etna, CA: Centre for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies)

Commentaries by Joy Clarkson