Luke 15:11–32

The Prodigal Son

Andrew Peter Santhanaraj

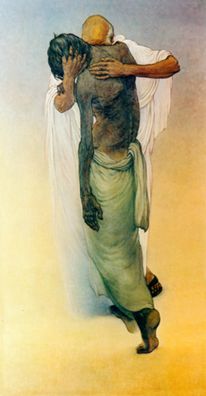

Prodigal Son, 1962, Ink drawing; ©️ 1962 Andrew Peter Santhanaraj

Lines That Lead Home

Commentary by Anand Amaladass SJ

Andrew Peter Santhanaraj (1932–2009), who had his schooling at the local Danish Mission before joining the College of Arts and Crafts, Madras, is now held in great esteem as a source of artistic inspiration in India.

In 2006, Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi, published a book on Santhanaraj with an essay by the art historian, critic, and curator, Ashrafi S. Bhagat. Its pages reproduce 47 works by the artist.

Among them there is just one picture on a Christian theme: Prodigal Son (1962). Yet by this single work, the author has influenced many of his younger colleagues. K.C. Paniker (the founder of the artists’ village in Chennai, Chola Mandal) was very much impressed by it for its quality of line. And the theme itself is appealing to Indian audiences in the cultural context of India. Several Hindu artists followed Santhanaraj’s example and have worked on it in different art media.

Perhaps, in its message, it shares some of the reconciling themes of certain other biblical scenes—the Cross, Jesus washing the feet of his disciples, the Last Supper—all of which have been taken up by a variety of Hindu, Muslim, and Parsi artists in India.

The gesture of prostration by the son as portrayed here has a particular cultural significance in India, where high caste people demand this sort of obeisance from the people of the lower strata of the society, a sign of subjugation or slavery.

Yet this is more than subjugation; this is homecoming. In the background of the work, musicians and dancers celebrate the son’s return with zest and energy. And this homecoming can be read as both the biblical son’s and also the artist’s. Ashrafi Bhagat comments that ‘wittily Santhanaraj parodies his own return’ (2006: 30). Long experimentation with Western methods and techniques, and an intense struggle with himself, eventually brought Santhanaraj to a mature style and to a new independence of spirit that was fully his.

In this personal liberation, there can be read something of India’s own journey as a nation. Bhagat observes that this scene seems to convey something of ‘national character and ethos’:

It is this quality of his art that makes his works seminal within the Madras group.… Prodigal Son … enthuses about a return to national identity through the re-inscription and approximation of [both the] vernacular and canonical imagery of art. (Bhagat 2006: 30)

References

Amaladass SJ, Anand and Gudrun Löwner. 2012. Christian Themes in Indian Art (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors)

Bhagat, Ashrafi S. 2006. A.P. Santhanaraj (New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi)

Frank Wesley

Forgiving Father, 20th century, Oil, 183 x 61 cm, Hiroshima Girls’ School, Japan; ©️ Family of Frank Welsley

Mercy and Misery Meet

Commentary by Anand Amaladass SJ

Indian–Australian artist Frank Wesley’s (1923–2002) interpretation of the parable of the Prodigal Son is a unique one. The Prodigal Son is portrayed as an Indian from a discriminated-against caste: emaciated, and without shirt. The bare-bodied figure reflects a familiar scene in countless Indian villages. It carries a cultural overtone.

In India only two kinds of people appear bare-bodied: the Brahmins at the temple while offering sacrifice, and those stigmatized as outcaste by elite Indian society. It is rather ironical to compare these two, because the one is bare-bodied for religious reasons (when coming before the deity), while enjoying prestige and often economic status in society. But the outcaste—impoverished, discriminated against, and pushed to the periphery of society—is bare-bodied because he cannot afford to clothe himself better. It is precisely such a one whom the merciful father embraces here: the emaciated and humiliated son of society. Miseria et misericordia: mercy and misery meet.

The bare-bodied image evokes further social significance where (as in some places) the outcaste even today cannot walk with shirt on or with sandals through the streets of high caste people. There was a time when the women of certain communities were not allowed to wear a blouse or cover their bodies above the waist, and were fined if they sought to cover their breasts. Christian missionaries fought against such legislation and brought about some change.

By the image of the father in the parable, I believe that Wesley reminds us of this history, and the need to revisit and remember it.

The father in Wesley’s interpretation of the parable looks like Mahatma Gandhi who also championed the cause of these discriminated people by addressing them as the ‘children of God’ (Hari-jan)—a term Gandhi coined. But a change of name does not automatically change the reality.

This image evokes a great deal to Christians who call Jesus the ‘dalit’ (oppressed one; see Arulraja 1996). Jesus who took sides with the poor and the outcaste becomes a pertinent symbol of liberation of the ‘untouchables’ in Indian society.

Naomi Wray, who wrote the biography of Frank Wesley, sums this work as follows:

This painting is the artist’s masterpiece—the fine translation of the Christian hope into Indian cultural terms, the most sensitive depiction of the relationship between God and his children and the richest artistic expression of divine love. (Wray 1993: 44)

References

Arulraja, M. R. 1996. Jesus The Dalit. Liberation Theology by victims of untouchability, an Indian version of apartheid (Hyderabad: Jeevan Institute of Printing)

Wray, Naomi. 1993. Frank Wesley. Exploring Faith with a Brush (New Zealand: Pace Publishing)

S. Jayaraj

Formation of a Prodigal Son, 2021, Mixed media, 30 x 42 cm; ©️ S. Jayaraj

The Prodigal Father

Commentary by Anand Amaladass SJ

All artists who have treated this episode have their own preferred moment to depict, through which they call the wider story to mind. Some paint the famished son amidst the pigs, some others the moment of return, and others again the celebration that follows. Each of these creative images is a visual commentary on Scripture, opening a field of interpretation rather than defining just one ‘meaning’ for the story, even though it is the same narrative that inspires them all.

The choice of focus—of the moment depicted—also tells something about the background of the artists, not merely the medium used or the polished style of their professional training but also their social status, their involvement with the society in which they live.

The artist Jayaraj S. is based in Chennai, typically working in a combination of pencil and paint. His work focusses on rural sections of Tamil society, and members of fishing communities, and gives voice to their cause through images. He has drawn several paintings on Christian themes, interpreting the gospel narrative in an Indian context. One of them is his interpretation of the Prodigal .

His interpretation of the story centres on how the loving father trains his wayward son by giving him freedom till he repents and returns home.

In the works of Frank Wesley and Andrew Peter Santhanaraj which are elsewhere in this exhibition, the first moment of the son’s arrival home takes centre stage. This is moving indeed to any onlooker, highlighting as it does the repentant son.

But Jayaraj captures the next moment when the father accepts him without any reservation and honours him by placing him on a pedestal, since his dead son has come home alive. Here the joy of the father gains prominence and his own prodigality is on display. The father–son relationship is cemented.

It may speak especially powerful to a context where life is precarious, and to a community whose cement is found less in material goods than in relationships.

Andrew Peter Santhanaraj :

Prodigal Son, 1962 , Ink drawing

Frank Wesley :

Forgiving Father, 20th century , Oil

S. Jayaraj :

Formation of a Prodigal Son, 2021 , Mixed media

Prodigal Perspectives

Comparative commentary by Anand Amaladass SJ

And he arose and came to his father. But while he was yet at a distance, his father saw him and had compassion and ran and embraced him and kissed him. (Luke 15:20)

The three artists chosen here are Indians who depicted the parable of the Prodigal Son.

Their interpretations give a local touch to the story, for their cultural moorings are in contexts where the large majority of people are treated by the elites as untouchables, unfit to be treated as equal human beings. The parable assumes a greater significance in such contexts when the portrayal of the father and the son includes the posture of prostration on the ground before the father (A. P. Santhananaraj), or explores the bare-bodied, emaciated look of the son (Frank Wesley) which is a familiar sight even today. Such body language speaks volumes about the depth of degradation to which human beings in Indian society have been (and can still be) subject.

Yet in an Indian Christian context where Jesus himself is sometimes read as a ‘dalit’, the depiction of the Prodigal as also a ‘dalit’ is powerful. Often in Christian tradition the Prodigal is held up as a type of the sinner. Yet, we may find ourselves invited to see a radical identification between him and the Saviour, who shares the depths with him.

Jayaraj S. looks at the wayward son with a modern sense of how youth wants freedom to discover life for itself. The loving father with his experience knows that his son is not mature enough to face life, but handles him in an admirable way. Though he does not disown him, he releases him. Then he waits for his return, and welcomes him with a father’s concern when he comes back.

In fact, Mahatma Gandhi quoted this parable of the Prodigal Son to show how his idea of ahimsa (non-violence) is illustrated in the way the father deals with his son. The father lets the younger son go his own way till he realizes what he has done with his life and comes back repentant asking forgiveness. This way of correcting the wayward son is, according to Gandhi, a non-violent way of forming the young (Gandhi 1965: 195).

This theme is quite topical in present day Indian families, where younger people are taken up with the opportunities of modern life and run away from parents looking for better material comfort and success. Meanwhile, the parents are left alone in anguish longing to see their children. It is the fate of many parents, and when it occurs the link between young adults and their elders is lost—to the anguish, perhaps, of both. Traditional father–son relationships fade, replaced by unresolved uncertainties. Maybe the departed will realize sooner or later that what matters in life is not merely material security, but relationship with one another. Maybe this realization will awaken in them an awareness of the presence of divine providential care.

The purpose of juxtaposing these paintings by three artists on the same theme is not to write a treatise on the artists themselves, but to record what their visual representations evoke in the minds of the onlookers; how the images speak for themselves without the artists standing nearby telling us what they intended. The paintings may speak differently to different people.

The things that strike me most are the following: the faces in these works reflect a cultural variation that is different from the Western images that have typically dominated the history of art, namely, the rural faces of simple people. Their socio-cultural history is hinted at in their portrayals—whether as bare-bodied or as falling prostrate. And the appeal of the forgiving father ready to welcome the son evokes for me the proper character of the Christian presence in India, despite the violent opposition it faces from some quarters at present.

References

Amaladass SJ, Anand and Gudrun Löwner. 2012. Christian Themes in Indian Art (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors)

Damm, Alex. 2020. ‘Gandhi and the Parable of the Prodigal Son’, in Biblical Interpretation, 29.1: 90–105, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15685152-00284P04

Gandhi, M. K. 1965 [1920]. ‘Religious Authority for Non-Co-operation’, in Young India: Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 18 (New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting)

Commentaries by Anand Amaladass SJ